The Art Department

The Mothers vs. The Beatles

I talked to Paul McCartney on the phone and his response was "What? You talk business? Talk to my lawyers." So I had my lawyer talk to his lawyer and as a result the cover was held up for thirteen months. Nice people, these Beatles.

Remember the first time we went to England I got a phone call from Paul McCartney's, "Would you like to come over and have tea" and so forth, and so I discussed this with a number of other people 'cause I was afraid he was going to slip me some acid. I was afraid I would wind up like that, and so after it I said. They just told me, "Well if you go over there, don't drink anything, you'll be OK, don't eat nothing, don't drink anyhing, if somebody comes at you with a needle, run." So I was supposed to go over there but then I found out I had to go to Copenhagen the afternoon I was supposed to go over his house, so I remember getting on the phone and talking to him and said, "Hello, Paul, is that you, Paul? Well listen, this is Frank, I can't make it over there today but I had something I want to discuss with you, you know we got an album that's got a cover that sorta looks like Sgt. Pepper, and I wonder if there would be any problems you know, if you guys complain if we did this cover that was making fun of the Sgt. Pepper album." And at the end of the phone I could see the guy going . . . Finally he says, "You mean, you talk business?" And I said, "Well, you know, I figured it'd be better this way instead of calling up your lawyer." And he says, "Well, I think I have to discuss this with the other members of the group, but our attorney I'm sure would be able to blah blah blah . . ." And eleven months later, the album finally came out, after going through a bunch of shit with their attorneys, and so forth, and there you have it.

[...]

I'll tell you one other thing: the place where the cover is printed is called "Queen's Litho" just outside in NY, and there's this sheet, I wish I still had one of them, I don't know whether you understand about how they print things, but they don't do 'em one at a time, they gang 'em up on big sheets of paper, and then they cut 'em apart. Our covers were so similar, we're using the exact same color of ink and everything that they were using on their cover, to the point that they were running 'em on the same sheet, you know. Like there are these big sheets, like this, the half has got the real one on this side, and ours on that side, and they're really funny to look at, they make great wallpaper.

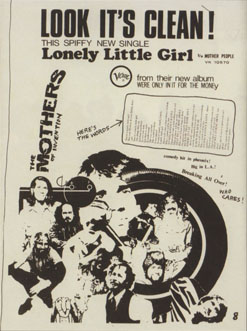

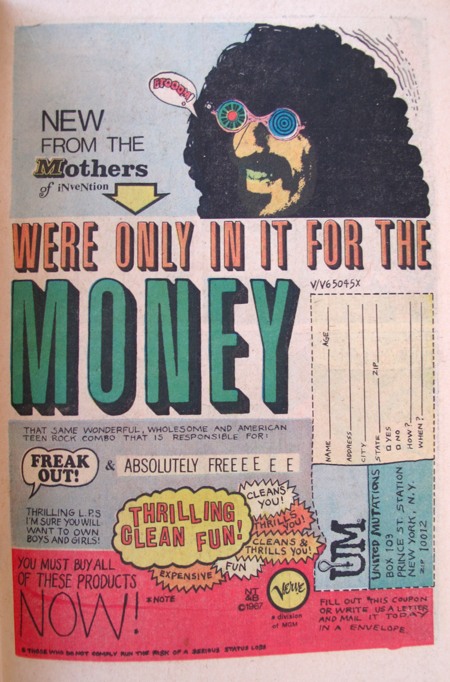

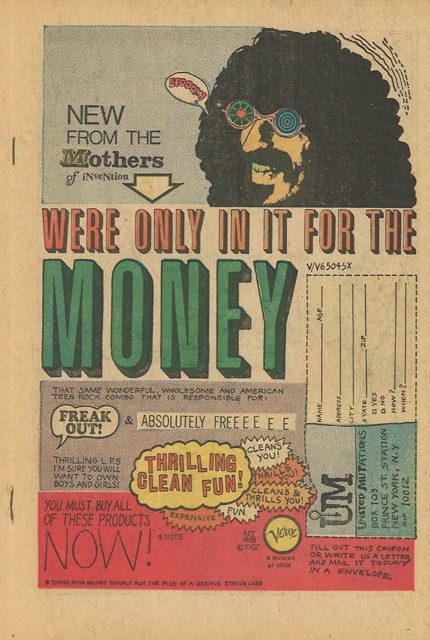

Us: We were intrigued by the insert in your "Only In It for the Money" album. Did it help your sales?

Frank: That cut-out page cost us 66,000 orders in California. Some stores refused to sell the album because of the nipple on the cut-out page. They were completely unaware that it belonged to one of the guys in the band. But that's O.K. It's still selling. They can't keep it from selling.

LS: What I wanted to find out was how soon did you suspect that you were going to have legal problems, and can you go into that a little bit?

CS: No one thought about it except MGM. I can't talk about what Frank's dealings were with them—but my take on the whole thing is that the legal issue was mostly just MGM being pissy about everything and not even wanting to even take a chance on there possibly being trouble; because as far as I know the Beatles didn't really have a problem with it . . .

LS: It's always the lawyers. I understand, yeah . . .

CS: I think it mostly was—you know, what I knew was that, oh, MGM says, oh, you gotta put bars over everybody's faces, oh, MGM says you gotta turn it inside out . . .

Cal Schenkel

FZ, interviewed by Michael Heinze, July 30, 1990

In the case of Cal Schenkel, I saw his portfolio and I hired him.

When I first met [FZ] in New York, the art studio was in his apartment—but that was only for a brief period. I didn't actually live there, but I would commute to work at his place. When we moved to LA when he had rented the log cabin, I had a wing of it. It was my living quarters and art studio, which I rented separately from them. There was probably more of a chance to fraternize when I lived in that close proximity than when I didn't, but even when I lived in my own place I'd be hanging out a lot and listening to what he was doing with the music. I think that it was just that I happened to fit the mold. I'm not sure I totally did understand it, but it just happened to coincide with what I was doing.

"There was an album he was working on before Sgt. Pepper hit, separate from Lumpy Gravy," claims Cal Schenkel[...]. "I can't remember much about the material for that album—some of it was an extension of the stage shows. But when Sgt. Pepper came out, there was this switch: 'Let's do something with this.' Whatever I was doing for that album, which was very preliminary, suddenly became a parody of Sgt. Pepper."

By the spring of 1967 Schenkel was back in the Philadelphia area, where he was born and raised. Zappa, who had art directed the first two Mothers album covers himself, was looking for an artist to take over, and Schenkel's then-girlfriend, a Zappa collaborator, showed the musician some of the artist's work. Schenkel and Zappa got together in New York, where the Mothers had a lengthy performance residency, and Zappa hired him immediately to work—in quick succession—on some advertisements for the forthcoming Absolutely Free record, on the live light show and then the Sgt. Pepper's parody cover for We're Only In It For the Money, which was designed to Zappa's satirical specifications.

Nifty, Tough & Bitchen

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

PACKAGING CONCEPT: NIFTY,

TOUGH & BITCHEN Youth Market

Consultants for

BIZARRE PRODUCTIONS & Herb

Cohen

We maintain a small agency called NT&B [Nifty Tough & Bitchin'] which turns out our album covers. We turn them out for other people if they can afford it. But we usually ask a lot of money and they go away.

The Mothers Of Invention

Ray Collins & Don Preston

We weren't working that much because of the studio commitments and I was having a hell of a time paying my rent in Woodstock. During one of those recording sessions, Frank and I had our little discussion about "If We'd All Been Living in California . . . " I had absolutely no idea that it was going to end up on an album [...].

Right after we had that band meeting, Ray Collins quit the band again and went back to California.

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

DON PRESTON: retired

Open City, November 3, 1967

Duke of Prunes Ray [Collins], former vocal lead with the Muthas, has split from Zappa & Co. and returned to L.A., followed by keyboard master Don Preston. Preston has been sitting in with the Fraternity of Man (the band, not the dancers) with Collins digging from the sidelines. In case you didn't know, the Fraternity is led by yet a third Zappa alumnus, guitarist Eliot [Ingber], who was on the Muthas' first LP but not the second.

I decided, fuck all this shit in New York, I'm going back to L.A. to my wife and kids. So I went back to L.A., found out where my wife was living, and this big guy answered. And I said, "Fuck this shit too." So I called Frank and said, "Let me back in the band," and flew back to New York. I was gone for about a week, but during that week, they did the liner notes.

"The Top 100 Albums Of The Last 20 Years," Rolling Stone, August 27, 1987

By summer's end, Zappa was attempting to entice his weary musicians into the local Mayfair Studios to begin work on Money. However, he says, only bassist Roy Estrada and multi-instrumentalist Ian Underwood "pretty much stuck with it. The rest of the guys didn't really like it. Most of them had quit at least five times. It was hard to get 'em to show up to sessions. That's why I did most of the stuff."

Mothers' Auxiliary

Eric Clapton

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

ERIC CLAPTON (noted philosopher & guitarist with THE CREAM) has graciously consented to speak to you in several critical area. (Courtesy ATCO Records.)

Could you give me a hint at where Eric Clapton plays on on We're only in it for the money?

He does not play, he only talks.

How did Eric Clapton come to appear on We're Only in It for the Money?

I met him someplace in New York; I can't remember where, maybe at one of our concerts. He played with the Mothers once at the Shrine in Los Angeles and came over to my house, but I haven't been on speaking terms with him for some time now. He was just in New York one day hanging out, so I invited him over to the studio to do the rap that's on We're Only in It for the Money. People think he's playing on it, but he's not; the only thing he's doing on there is talking.

Did the two of you ever sit down and trade ideas on guitar?

No, he wasn't that kind of musician as far as I could tell; he wasn't the jamming type. When I used to live in a log cabin I had some amps set up in my basement, and he came over one day and played during one of our rehearsals. But he didn't like the amp; we were using Acoustics then, and he didn't like them. And remember when he came onstage at the Shrine? Nobody knew who he was. He came out and played the set, and nobody paid any attention to him at all, until he walked off, and I told the audience that was Eric Clapton.

Eric Clapton, interviewed by David Mead, Guitarist Magazine, September, 1994 (French translation by Olivier Galan)

Tu as été invité sur beaucoup d'albums, mais le plus bizarre doit être ta contribution à "We're only in it for the money" de Frank Zappa & the Mothers Of Invention.

Nous étions amis. Je l'ai rencontré quand je suis allé à New York avec Cream et les Who, pour le show de DJ Murray the K. Les Fugs et les Mothers jouaient dans Greenwich Village, B.B King était au Cafe A Go Go. New York était incroyable, les Mothers jouaient au Garrick Theater et personne ne venait les voir! Ils expérimentaient chaque soir, faisaient monter sur scène des vieilles dames de la rue avec leurs sacs en plastique, ou des marines en permission. Frank Zappa s'asseyait dans le public pendant que le groupe continuait à jouer. C'était de la folie. Il ma emmené chez lui un soir, a sorti un Revox, et m'a dit de jouer tous les riffs que je connaissais. J'ai pensé que c'était gentil de sa part de s'intéresser à mon jeu et j'étais plutôt flatté parce que je rencontrais un intellectuel de la musique. Il était très manipulateur, il a su faire appel à mon ego et à ma vanité, et j'ai tout mis sur la bande. Je crois qu'il avait bande sur bande d'artistes différents exposant leurs styles. Quand je suis revenu aux Etats-Unis, je l'ai appelé et il m'a invité en studio. Il voulait que je monte dans un piano pour parler, il y est monté le premier et il m'a dit "Je veux que tu te prennes pour Eric Burdon sous acide !". Et c'est ce que j'ai fait, je prononçais des phrases comme, je peux voir Dieu, tout ça. Avec lui, je me sentais hip et avant-garde, mais c'était toujours bizarre et drôle.

Une autre fois à L.A., je savais qu'il donnait une party. J'y suis allé et dès que la porte s'est ouverte, quelqu'un m'a mis une guitare dans les mains. Elle était déjà branchée, ils étaient prévenus et m'attendaient, j'avais marché droit dans le piège ! Plus tard encore, je suis allé le voir en concert et il m'a invité à jouer. Lorsque j'ai commencé mon solo, il a fait ses fameux signaux de la main en direction du groupe et ils ont changé de tempo un bonne dizaine de fois. Je ne savais plus où, j'en étais, complètement perdu ! Je l'aimais beaucoup, c'était un homme merveilleux.

Google Translate:

You have been invited on many albums, but the most bizarre must be your contribution to Frank Zappa's "We're only in it for the money" and the Mothers Of Invention.

We were friends. I met him when I went to New York with Cream and the Who, for the DJ Murray the K show. The Fugs and Mothers were playing in Greenwich Village, BB King was at Cafe A Go Go. New York was amazing , the Mothers played at the Garrick Theater and no one came to see them! They experimented every night, brought up old ladies of the street with their plastic bags, or marines on leave. Frank Zappa sat in the audience as the band continued to play. It was madness. He took me home one night, took out a Revox, and told me to play all the riffs I knew. I thought it was nice of him to take an interest in my game and I was rather flattered because I met an intellectual of music. He was very manipulative, he knew how to appeal to my ego and my vanity, and I put everything on the tape. I think he had tape on tape of different artists outlining their styles. When I came back to the States, I called him and he invited me to the studio. He wanted me to get into a piano to talk, he went up there first and he said "I want you to take Eric Burdon under acid!" And that's what I did, I uttered phrases like, I can see God, all that. With him, I felt hip and avant-garde, but it was always weird and funny.

Another time at L.A., I knew he was giving a party. I went and as soon as the door opened, someone put a guitar in my hands. She was already connected, they were warned and waited for me, I walked straight into the trap! Later still, I went to see him in concert and he invited me to play. When I started my solo, he made his famous signals of the hand in the direction of the group and they have changed tempo a good ten times. I did not know where I was, completely lost! I loved him very much, he was a wonderful man.

Pamela Zarubica

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

SUZY CREAMCHEESE: Telephone

The Recording Sessions

c.July-October, 1967

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

THIS WHOLE MONSTROSITY WAS

CONCEIVED & EXECUTED BY

FRANK ZAPPA AS A RESULT OF

SOME UNPLEASANT

PREMONITIONS, AUGUST

THROUGH OCTOBER 1967.

The Mayfair Sessions

c. July-September, 1967

We're Only' In It For The Money was eight-track and done in a real primitive studio.

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

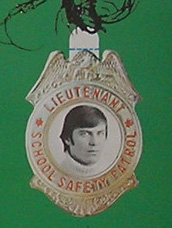

GARY KELLGREN (picture in badge

on cut-out page), engineer for two

months of basic sessions at MAYFAIR

STUDIOS is the one doing all the

creepy whispering.

Unidentified source

[FZ, Gary Kellgren, Roy Estrada, Tom Wilson]

[Ian Underwood, unidentified girl, FZ.]

[Ian Underwood, Gary Kellgren.]

[Tom Wilson, Phyllis Altenhaus.]

Frank Zappa Sessions Information, compiled by Greg Russo, August, 2003

08/02/67 Mayfair Studio, New York—tracks not specified

08/03/67 Mayfair Studio, New York—tracks not specified

08/07/67 Mayfair Studio, New York—tracks not specified

08/08/67 Mayfair Studio, New York—tracks not specified

08/09/67 Mayfair Studio, New York—tracks not specified

The Apostolic Sessions

c. October, 1967

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

DICK KUNC (unfortunately invisible),

record & re-mix engineer for the final

month of recording at APOSTOLIC

STUDIOS is the one responsible for the

cheerful interruptions.

I went to New York, and I got this job at this incredible twelve track studio. Well, I didn't know from twelve track, I thought four track was really hot stuff. So I went in there and they said, "Here's the board. Learn it." Here ya go, "Your first client's coming in in five minutes." Well, my first client was Frank Zappa.

I picked a downtown location, in the Village, as that's where all the musicians were. Be where you're comfortable. After all, only the execs were uptown. It was a loft building on 10th St. near Broadway, with a hand-operated freight elevator its primary access, one where the elevator had no walls and worked by pulling a cable to make it start and stop. That was a golden opening opportunity—our artist/"elevator man" Nicky Osborn soon had the entire darkened six-story shaft detailed in black-light psychedelic murals, and his personal welcome in full Viking costume definitely made a serious start on the way up. Way up. [...] The rest of the studio followed suit, with totally controllable theater lighting throughout, so whatever the state of your insides, you could make the environment match.

[...] I insisted on the first independent cue system on any mixing console, ever (built by Lou Lindauer, his Automated Processes' opening gambit, who brilliantly nursed us through our demanding technology changes). And, of course more tracks (how quickly you run out at only eight)—we went to twelve because that was as many as Scully could crowd onto a relatively-editable one-inch tape transport in this first-of-a-kind machine they built to our specs. And faders, instead of pots (goodbye '50s sci-fi flicks), also a first, and the new-fangled solenoids . . . best of all, everyone could touch them all, no union, except don't spill your Coke on the board! All that, and teenage whiz engineer Tony Bongiovi (later, brother/producer of Jon Bonjovi) were enough to launch us into the ozone.

When we opened in the spring of '67, everyone in "the biz" said we were crazy: no one would come downtown, nobody needed twelve tracks, and our whole style was VERY un-businesslike . . . our name was Apostolic Studios, after our twelve tracks and unabashedly spiritual (though not particularly Christian) tilt, and clearly we were nuts.

Well, inside three months we were booked solid. The Critters, Spanky And Our Gang, the Serendipity Singers, the Fugs, Rhinoceros, The Silver Apples, Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, Alan Ginsberg, the Grateful Dead and most of all Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention found the qualities of user-friendly tech and musician-friendly ambience to be just what the doctor ordered. Six months after that, Gary Kellgren, who had made an early reconnaissance visit to Apostolic, opened Record Plant with an identical 12-track Scully and similar board and ambience, and shortly thereafter Jimi Hendrix built Electric Ladyland downtown on 8th St., just blocks away. [...]

The studio retains memories that are unique to its origins. [...] Generations of Mothers trooping in and out for "Lumpy Gravy" and "Uncle Meat" sessions . . . and in the process recreating the then-rare "flange" effect, employed by Zappa and our engineers at Apostolic using a reverse-phased, slightly trailing variable-speed controlled 2-track Scully. About the "flange," engineer John Kilgore remarks, "I first heard it on Toni Fisher's 'The Big Hurt' in 1959. then on 'Itchykoo Park' by the Small Faces in early '67, and on Hendrix's second record released in '67. I remember Kunc and I bashing our brains out trying to figure out how it was done. Finally, Dick called up Gary Kellgren and asked him how point blank. Gary, bless his heart, told him."

I

recall the API console as a sea of

blue Formica, a wondrous machine praised

by Frank Zappa, with sparkling new

arc-shaped British Painton

faders. Sort of "proto-faders," actually, the Painton controlled a

linear series of many individual make-and-break contacts. On very quiet

passages you could actually hear the tiny "bip-bip-bip" as it went

from contact to contact.

Each

input position had rudimentary

equalization available, but it amounted to little more than glorified

bass and

treble controls. We had a pair of Lang equalizers mounted externally to

help

the cause. The input positions were normalled to their corresponding

tape

tracks, but you could reassign any input to any tape track via the

patchbay.

For mixing you could also assign each input position to either left,

center, or

right. These were hard switch selections. There were no pan pots on the

input

positions. You could patch into the console's two independent pan pots

but that

was it.

Three

Melchor compressors did give

us a smidgen of ceiling control in extreme cases. They were better

known for

their pronounced and dramatic "breathing" effects in which the

momentarily suppressed background sound comes rushing back up in volume

after

the peak has passed. Also external to

the console was a very fast (for its day) limiter that used a light

source

coupled to an optical detector to do its work.

The

prototype Scully twelve-track

machine used one-inch tape. It had twelve sets of their normal

full-size

rack-mounted electronics, the ones they put in their mono and two track

machines—imagine twelve of those babies, each one with a complete

set of

knobs and full-size meter! It was just huge—but it worked. One problem with the machine was bleed-over

while recording on adjacent tracks, so we'd record on odd-numbered

tracks

during the first pass, and then overdub in between the initial tracks

from then

on.

The

machine had one neat trick,

though. You could take a one-inch tape with eight tracks recorded on it

by an

eight-track machine, put it on our twelve-track machine, and add four

more

tracks! You ended up with twelve very

mixable tracks, all of which still had very acceptable signal to noise

ratios,

and it made us completely compatible with other 8-track studios.

The

primary "echo chamber"

was one of those "state-of-the-art" EMT vibrating steel plate deals.

Inside a huge wooden case a sort of loudspeaker was attached to one

corner of a

metal plate that must have measured maybe four feet by eight feet. When

you fed

a signal to this "speaker" it sent waves through the plate, sort of

like ripples on a pond. A transducer at the opposite corner picked up

these

waves, equalized them, and sent them back as echo.

There were also some experiments with live speakers

and

microphones in the stairwell of Apostolic's ancient building, much to

the

dismay of the residents of the other floors, and whose complaints

effectively

squelched our efforts.

What

gave the console its

saving-grace versatility was its extremely comprehensive patchbay. It

was the

old tip-ring-sleeve variety, left over from telephone company

technology,

though more than one unrepeatable take was destroyed by some bit of

studio dust

that got in there . . .

And

for microphones—a few Neumann

U-67 condenser mics with their accompanying power supplies, a few

borrowed

Sennheiser ribbon mics, a smattering of assorted decent dynamics,

including

those warm and indestructible cone-headed D-202s, and a motley gang of

one-of-a-kind items including an indestructible Altec "salt shaker"

routinely used for drums and a giant, mellow vintage RCA mike that must

have

recorded Bing Crosby or the Andrews Sisters in its youth.

In

the control room were large

hard-edged Altec monitor speakers, behind the console. Took a bit of

getting

used to. Plus the favored (by us)

KLH-6s up front that blew out all the time when the clients said

"louder," not to mention delightful Boze clones built by Gus Andrews,

our first reggae recording artist.

Apostolic

was a real Viking ship, a

gutsy voyage into the uncharted depths of new toys and new ideas from

which

came some of the cleanest recordings of that era.

Calvin Schenkel Apostolic Pictures

Photo: Cal Schenkel

95RR-inlay: photo by CS from one of the recording (actually mixing?) sessions at Apostolic (L to R—Richard [Kunc], FZ, Don Preston).

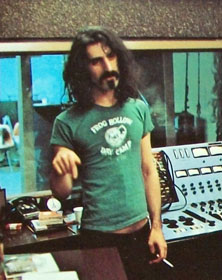

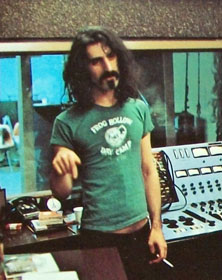

Hot Rats (1969) inside cover

[Hot Rats] inside photos by CS [...]: Top #[...]2, 3—Apostolic Studios (or Mayfair, I'm not sure which) ("Frog Hollow" T-Shirt courtesy Richard Isgrigg's brother), NY

The shot of Don [on the inside cover of Burnt Weeny Sandwich] is from Apostolic Studios (solarized & developed in the bedroom closet of Franks Charles St. NY apartment).

Mixing

"We were working in a studio in NewYork that had one speaker for every track," Frank told William Ruhlmann. "You sat in front of eight speakers. And you couldn't punch in and out without leaving an enormous click on the tape. It was living hell to mix something from that machine because everytime you had punched in to add a part, in advance of pushing that part up in the mix, you had to first duck it out to get rid of the click." [When The Music Mattered: Rock In The 1960s, by Bruce Pollock (Holt, Rinehart Winston,1983)]

Production

Liner notes by FZ, 1968

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER: TOM

WILSON (for MGM-Verve)

(in the high school sweater with no shirt

left front cover)

PRODUCED BY FRANK ZAPPA FOR

BIZARRE PRODUCTIONS

January first this year [Tom Wilson] left M.G.M.-Records to set up his own Tom Wilson Organization, a general talent agency and recording office.

Lenny Bruce & Our Man In Nirvana

He told us he wants to stage a Broadway musical science fiction horror story based on the Lenny Bruce trials. He'd also like to conduct an 84-piece rock & roll orchestra on the stage of Carnegie Hall and hypnotize the audience with his music.

Frank Zappa records a song with Lenny Bruce—called "Don't come in me"—for his new album.

In September, we're releasing The Mothers and Lenny Bruce. Spliced tapes of Lenny Bruce enmeshed with our members.

We're touring Europe in October. England, Holland, France, Sweden, Denmark. In November, we're releasing We're Only In It For The Money.

ZAPPA: We have some material that's going into the next album about the concentration camps in California—you're seeing this before the world even knows what the tune is because I turned these out the other day. These are going on the album, The Mothers and Lenny Bruce, which is due for September release.

KOFSKY: Well, how does that go? Is it going to be real Lenny Bruce on there?

ZAPPA: Yeah. I'm editing the tapes of Lenny's and interspersing these special tunes, so we come up with an oratorio thing, and the name of the album is Our Man in Nirvana.

FZ, interviewed by Co de Kloet, May 24, 1980

In the Lenny Bruce tapes, the original idea that was offered to me in around 1966 when we were recording with MGM, they had some Lenny Bruce tapes. And they wanted me to make music to go with the tapes, so they could release an album that was Lenny Bruce and The Mothers, see? And I thought about it and I said, "That man doesn't need my music to make his ideas go." So I refused to do it. [...] Our Man In Nirvana was the title for the album that they wanted me to do with music in it.

FZ, interviewed by Alan Handelman and Todd from Durham, WQDR-FM, Raleigh, July 23, 1983

[Our Man In Nirvana] was a project that at the time we were signed to MGM, a guy there had access to a bunch of tapes of Lenny Bruce. I don't know whether you know who that is. They had these Lenny Bruce tapes, and somebody thought that we should do some music to go along with the tapes. And that's what that album was gonna be called. Because he was already dead at the time that the project was suggested. That's where the title comes from.

Additional informant: Charles Ulrich

1. Are You Hung Up?

EC: ARE YOU HUNG UP? ARE YOU HUNG UP?

Clapton remembered being told, "'I want you to pretend to be Eric Burdon on acid.' And that's what I did—I was just saying, 'I can see God', and all this stuff, and it was just funny to be involved with these people." [Guitarist, June, 1994, "The Guitarist Interview," by Davide Mead].

chorus: [...]

ERIC CLAPTON & CHARLOTTE

Gary Kellgren: One of these days I am going to erase all the tape in the world . . . In the world . . . world . . . Tomorrow I may do it . . . All the Frank Zappa Masters . . . Nothing . . . Blank . . . Empty . . . Space . . . That's what they are now . . . Blank . . . Empty . . . Space . . . Oh, I know he's sitting in there, in the control room now, listening to everything I say, but I really don't care . . . Hello Frank Zappa!

That's Gary Kellgren, who was actually the engineer on We're Only in It for the Money. And he was a funny guy—a suffering individual during those days, because he had a studio (Mayfair) that had the only 8-track in New York City at that time. It was kind of a homemade rig, and he was recording 18 hours a day, and he had no private life, no social life. He was just run down. We had to get our album done and we were forced to work with a guy where I knew that just by our going and doing our session we were making his life more miserable by the minute. He would do, maybe, three or four bands per day, and it was just grinding him down. He was living on leapers and beer, and so I decided one day to just let him blow off a little steam: I put him out in the studio—I became the engineer and let him talk into the microphone. That's where all the creepy whispering comes from.

3. Concentration Moon

I believe that San Francisco and its citizens were used by the United States government for LSD experiments, psychological warfare experiments, and germ warfare experiments during that period of time. I think that the whole Haight-Ashbury phenomenon was manufactured, and I think that the people who were victimized by those drugs during that time ought to sue the government. You're looking at a place that was chosen as the home of the manufactured zombies.

After the CIA discovers this potential weapon, where are they going to try if out on large number of people? In an urban setting. Take a map. Stick a pin. San Francisco gets the vote. You know those, funny little camps they were opening up during the '60's? The ones where they put the Japanese people during World War. They were sprucing them up in the 1960s. They were opening them up.

I don't think they feared the students or needed a place to lock them away. I think the camps were a safety valve, in case the chemical experiments failed and you had tens of thousands of uncontrolled potential murderers on the street. If they dosed 'em too much and everything got out of hand, the only answer would have been to round them up and stick them in those camps.

also at the same time I get to work with The Velvet Underground which is as shitty a group as Frank Zappa's group

Myth: The Mothers of Invention, who were also on the MGM subsidiary Verve Records, used their influence to delay the release of the banana album (not issued until almost a year after most of it was recorded) so that it wouldn't interfere with the Mothers' own debut LP, Freak Out!

Reality: This is almost impossible to prove or disprove, unless some smoking gun comes to light in form of a specific memo from the Mothers' management or some such source. Yet certainly several of the Velvets were suspicious that something of the sort took place. In his autobiography, John Cale speculated that Verve's promotion department took the attitude "zero bucks for VU, because they've got Andy Warhol; let's give all the bucks to Zappa." And in his April 1981 NME interview with Mary Harron, Morrison claimed, "I know what the problem was: it was Frank Zappa and his manager Herb Cohen. They sabotaged us in a number of ways, because they wanted to be the first with a freak release. And we were totally naive. We didn't have a manager who would to go the record company every day and just drag the whole thing through production." Even way back in a November 1968 interview with Open City, Lou Reed griped, "Our first album was released six months late, right? Because the record company was afraid because of 'Heroin' and, two, because the manager of the Mothers didn't want Frank's album to be like our first one—there were no psychedelic albums no hip albums, then, and theirs was coming out first...I'm not saying anything evil towards anybody, but there was panic, and ours came out six months later."

But as for hints subsequently dropped that the Mothers were determined to have their album out first even if it meant pushing the Velvets' debut back, there's a simple reason why Freak Out! was ready for release before The Velvet Underground & Nico. It was recorded first (from March 9-12, 1966; the first sessions for the banana album didn't take place until mid-April), and was officially issued on June 27, 1966, long before producer Tom Wilson's wish to make the banana album more commercial with the addition of "Sunday Morning" was fulfilled in November.

10. Flower Punk

I'm goin' to the love-in to sit & play my bongos in the dirt.

Dominic Priore, Riot On Sunset Strip, 2007, p. 21

Based on civil rights activities such as 'sit-in' demonstrations and 'teach-in's, Peter Bergman of Los Angeles comedy troupe The Firesign Theater coined the term 'love-in.' This arrived in reference to events such as the first Renaissance Pleasure Faire, which debuted in 1964 as a folk music even put on by LA underground radio station KPFK.

The 'Hippie Riff'

William M. Reid (affz, February 18, 1997)

Can anybody spot the quote that occurs in the classic WOIIFTM tune, "Flower Punk"? I'm not refering here to the "Hey Joe" 3/8 chord progression that is used for the verses, but to the instrumental wah guitar (or is it keyboard?) riff that happens in 7/8 throughout the song (and is repeated until it degenerates during the 2nd half)

John Henley (affz, February 18, 1997)

It's been identified as the hook lick from "Needles and Pins," composed in 1963 by Sonny Bono and Jack Nietzche. First recorded in '63 by Jackie De Shannon, but an international hit in 1964 for The Searchers.

Musically, the northern bands had a little more country style. In L.A., it was folk-rock to death. Everything had that fucking D chord down at the bottom of the neck where you wiggle your finger around—like "Needles and Pins."

I do remember teasing Jack [Nitzsche] about one line that he had written and wanted me to play on guitar. "Jack, that 4th doesn't belong in that chord, it won't sound good," and Jack, smiling replied, "Carol just play it anyway, it'll be OK" . . . and that was the Needles and Pins guitar line.

13. Let's Make The Water Turn Black

Now believe me when I tell you that my song is really true

I want everyone to listen and believe

It's about some little people from a long time ago

And all the things the neighbors didn't know

"Let's Make the Water Turn Black" was a true story about two brothers, Ronnie and Kenny Williams—a couple of musicians I knew in 1962 during the early Paul Buff/Pal Records era (it was Ronnie who introduced me to Paul).

It is difficult to describe these guys, their family and their 'hobbies'—so much of it will sound like fiction—however, let me assure you that this has all been documented on tape, in their own words.

Early in the morning Daddy Dinky went to work

Selling lamps & chairs to San Ber'dino squares

The family was from Arkansas. The Dad (Dink) was a furniture salesman in San Bernardino, but, back in the way-back-when, he used to play 'bones' or 'spoons' in a minstrel show. To relive the golden days of yesteryear he would, from time to time, force his children to accompany him (Ronnie on guitar, Kenny on trombone) in a living room replay of a minstrel routine called "Lazy Bones."

And I still remember Mama with her apron & her pad

Feeding all the boys at Ed's Cafe!

I can't remember the Mom's name, but she was a pleasant, hardworking lady who helped pay the rent by waitressing at a place called Ed's Cafe, in Ontario.

(Ronnie helping Kenny helping burn his poots away!)

They were fascinated by, and constantly perfecting new techniques for, The Manly Art Of Fart-Burning. Kenny explained to me that it was scientific—that it demonstrated (this is a real quote) "Compression, ignition, combustion and exhaust."

Ronnie saves his numies on a window in his room

(A marvel to be seen: dysentery green)

After the [raisin wine] explosion [in San Diego], the family moved to Ontario, California. Kenny got arrested for something (I don't know what) and went to 'reform school.' In taped interviews he refers to this experience by saying: "While I was away at boarding school—"

So, while Kenny was away at 'boarding school,' Ronnie and his pal Dwight Bement (eventually the tenor sax player for Gary Puckett and the Union Gap) had the house pretty much to themselves. Both parents were working, so the guys were in Dropout Heaven, spending their days playing poker in Ronnie's bedroom.

During the games (we can't be sure how this part got started), they began a competition of 'booger-smearage'—on the window by the bed. This window eventually became opaque. One day, the Mom stuck her head into the room and got hysterical, demanding immediate removal of the frosting. According to Ronnie: "We had to use Ajax and a putty knife to get the damn things off."

Dwight Bement (quoted in Splat's Zappapage)

After I went back to San Diego in 1961, [...] I think I was in San Diego about two days when Ronnie called and asked me to come up to Ontario and join his band. I didn't hesitate. He was living with his parents at the time so I moved in. This is when the infamous 'Green Window' project was launched. You can read about it elsewhere.

While Kenny & his buddies had a game out in the back:

LET'S MAKE THE WATER TURN BLACK

And all the while on a shelf in the shed:

KENNY'S LITTLE CREATURES ON DISPLAY!

Eventually, Kenny came back from 'boarding school.' For some reason he didn't want to stay in the house, and so he took up residence in the garage—with Motorhead (this was before Motorhead moved in with me).

It was winter when they lived out there and, since there was no toilet in the garage—and not wishing to brave the elements—the lads relieved themselves nightly into some of the Mom's mason jars, lined up along the garage wall, awaiting the installation of next season's home-canned fruits.

Now, Ronnie wasn't the only cardplayer in the family—Kenny also liked to play—and on a few of those cold winter nights, Kenny and Motorhead hosted a few games for the other fun guys in the neighborhood. Eventually, the beer took effect, and everybody started reaching for the jars.

The jars weren't dumped—they were saved as 'trophies.'

Many games later, the boys ran out of jars. The solution to this problem came in the form of a large earthenware crock (like the one Ronnie used to watch the raisins puff up in).

In a festive ceremony, all trophy jars were poured into the crock—just to find out how much piss there was around there ("Wow! Look at that! We're really pissin' a lot! Jesus H. Christ, what a lot of piss we got here! Haw haw haw . . . ").

Eventually, Kenny moved back into the house, and Motorhead moved in with me. One day, a few months later, Motorhead visited Kenny and, just for old times' sake, took a peek at the crock in the garage. Lifting the board which covered it, they beheld several 'denizens' swimming in the piss—unknown 'things' that looked sort of like tadpoles.

Kenny fished one out and plopped it on the shop bench. It had a tail, and a head which Kenny described as being "about as big as your little fingernail—white, with a black dot in the middle of it . . . "

Motorhead poked it with a nail and "some clear stuff came out." Proud of their scientific discovery, they informed Dink. They were then instructed by the bewildered furniture salesman to "pour that whole damn crock down the toilet!," which is what they did—and to this day, friends, somewhere in the depths of the Ontario sewage system, horrible jelly-wigglers gurgle and multiply—waiting for their moment of 'heavy rotation' on MTV.

Oh! How they yearn to see a bomber burn!

Color flashing, thunder crashing, dynamite machine!

(Wait till the fire turns green . . . wait till the fire turns green)

WAIT TILL THE FIRE TURNS GREEN!

Dwight Bement (quoted in Splat's Zappapage)

We also enjoyed burning poots (farts). One time FZ was over so we decided to show him the fine art of burning poots. We were in the Kenny's bedroom, if I remember. Ronnie jumped up on the bed and took off his pants. The seat of his underwear a big hole w/ threads hanging down. When he put the Zippo to it, there was a nice balloon of blue flame and the threads caught fire. The flame traveled up and set his anal hairs on fire. FZ fell against the wall in a fit of laughter. I guess he never forgot that because he wrote a song about it.

Ronnie's in the Army now & Kenny's taking pills

Ronnie Williams was drafted in 1963, and the draft board caught him in Sacramento, California!

Patrick Neve

I received an email from his cousin's son who told me that Kenny unfortunately died of an overdose sometime in the 70's.

19. The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny

[FZ] explained the title to Kurt Loder: "Before they started making dolls with sexual organs, the only data you could get from your doll was looking between its legs and seeing that little chrome nozzle—if you squeezed the doll, it made a kind of whistling sound. That was the chrome plated megaphone of destiny. [Bat Chain Puller: Rock & Roll In The Age Of Celebrity, by Kurt Loder (St. Martin's Press, 1990)]

Oh, "The Chrome-plated Megaphone of Destiny"? The percussive-type noises, the thing that sounds like little squirts and explosions, was done by using a box that we built at a studio called the Apostolic Vlorch [Blurch] Injector. It was a little box this big (Zappa holds an imaginary small box with both hands) with three buttons on it. The console at the studio in New York where we used to work, Apostolic, was unique. In the sixties the audio science was growing, and people were trying all kinds of different things, and there was a lot of non-standard equipment around. This particular console didn't have a stereo fader; it had three master faders—a separate fader for the left, the centre and the right, so you could fade out the centre and leave the left and right, or whatever. So these three buttons on this box corresponded to inputs to the three master faders, and you could play it rhythmically.

The input to the box would be any sound source cranked up to the level of gross square-wave distortion. Any noise. You'd crank it up so that if it was printed non-stop on a piece of tape, you couldn't stand to listen to it. It would be trashed distortion. But as short little bits you'd get very complex, technicolor noise. When you hit the button and open up a little window of time, the structure of the distortion was a complex waveform, and that's where the bumpy, crunchy stuff comes from.

Then we had some backwards tape and tape slowed down and speeded up with the VSO, and were using parts of recordings of ethnic intruments. There's a tambora in there, a koto in there someplace. Some filtered tapes of industrial noises, horses, all collaged together.

I started doing that in 1962, before I had a record contract. I just experimented in this little studio they had, so I was well into music concrète techniques before I made a record.

FZ, interviewed on WDET, late 1967 (transcription by Charles Ulrich)

We began by creating what you'd call your basic blurch track. The blurch track was created by setting up in the studio two Neumann microphones and a pile of musical instruments: drums, chairs, music stands, sticks, waste baskets, anything that we could get our hands on that would make a noise if you hit it or kick it over. We put it in a pile in the middle of the room. Then, very carefully, we went out there and kicked things over, building up piles of stuff and knocking it over, beating on individual pieces of equipment, shuffling our feet, and just making random sounds. While we were doing this, the engineer was controlling the speed of the tape with a device known as the VFO, which is a Variable Frequency Oscillator. This controls the voltage to the tape recorder, which in turn controls the speed of the tape moving past the heads. If you speed the tape up as it goes past the heads, the sound of the material on the tape, when played back at normal speed, will appear to be lower in pitch. And, conversely, if you slow the tape down while you're recording it, the stuff comes out sounding higher. Well, what he was doing was varying the speed constantly during the time we were kicking these things over. So you'd get these strange effects where a pile of garbage is struck, begins to fall, and as it falls, it sort of goes into slow motion, and as the things begin to settle on the floor and stop rolling around, the speed suddenly becomes very high-pitched. We made approximately twenty minutes of this sort of background information.

This particular information was then subjected to a series of modifications. Modification one consisted of playing the tape backwards and adding to it what you call your tape delay reverb. We called this the dreamland reverberator at the studio. And what it is is a means of feeding back the original signal onto another tape and then back onto the original tape, so that you multiply the number of sounds being heard. It's like an echo repeat. And the number of echo repeats can be varied, and the speed at which the repeats will occur can also be varied. We had a very slow echo repeat on our blurch track. But because we were playing the blurch track backwards while we were putting the echo on it, a strange thing occurs: You have your original material on the tape. You play it backwards and add a tape delay. That means as a sound is hit backwards, you've got these repeats trailing off of it. Now when you play that forwards, what you get is a series of anticipations, creeping down onto each initial pulse. Instead of the echo following the note, the echo would precede the note, or the noise as it was in this case.

We then took the echoed tape and filtered it at random, through a device known as a Pultec filter. You have two knobs. One knob controls the filtering for low frequencies, and the other knob controls the filtering of the high frequencies. The knob on the bottom reads from fifty cycles on up to two thousand cycles. And the knob on the top reads from I think it's fifteen thousand cycles down to fifteen hundred cycles. If you turn these knobs at random, you are chopping out at random certain components of the noises which are on the tape. [...] you make a transfer onto another tape, what is present on the other tape when you are done is a filtered version of the original. Got that, kids? Okay. We now have a filtered blurch tape.

Now in recording you have a factor known as distortion. Distortion is something that happens when what you're putting on the tape is too loud for what the tape is capable of handling. And what it sounds like is noise. Real garbled nonsense. We created from our initial blurch track, which was labeled for laboratory convenience "Sock Hop", we created a sort of rhythm track for the rest of this piece. The piece in general consists of six tracks of woodwind instruments, five tracks of piano, and four tracks of laugh—was a human voice laughing in very strange ways. This was the voice of the engineer. We had to get him into the act because he was a good laugher. This was all accompanied by the blurch track. The way we did this— This was done on a twelve-track machine, by the way, at Apostolic Studios on Tenth Street in New York. We have the woodwind, piano, laugh material on several tracks. Now, as we're mixing it down, we're adding to it this blurch track. And the way we do this is: we have these things called faders, which are volume controls, which control the sound of the different tracks that are being combined onto a piece of quarter-inch tape, a little skinny piece of tape that's easy to carry around with ya. Now these faders are supposed to be adjusted so that the volume going onto the tape does not exceed a certain point. If you exceed that certain point, 1) you will never be able to get it onto a disc, and 2) you probably won't even be able to recognize it because it will be completely distorted. Well, we ignored this rule. The volume at which we re-recorded the blurch track was set at "piercing". And there are switches right by the fader, which—it's like an on-and-off switch. You turn the switch one way, the fader is engaged, and you can slide it up and down, back and forth and that will adjust the volume of the material that you're re-recording. But if the switch above the fader is in the off position, the fader is not operative. Got that? Okay. After we start the tape running along, we begin with the faders in the off position. That means although our source tape or the blurch track is rolling along, nothing is heard. See? Simultaneously, we are playing back the twelve tracks of woodwinds, piano, and voice.