Is the weight factor behind your choice of small guitars?

Yes, I have three of them, and I don't wear them; I play them. I have one Strat and two baby Les Pauls. They were made by D'Mini. [Ed. Note: These models are called the Les Paule and the Strate by their manufacturer, Phased Systems.] The D'Mini Strat that I have is unbelievable; you can't believe the noises that come out of that thing. It's ridiculous, I'm having a special one made with a little bit deeper body on it so that I can have a locking vibrato put on.

How are those guitars tuned?

The little Les Pauls are tuned up to A, and the Strat is tuned to F#. The relationship between the strings is the same as on a standard guitar.

Are special strings used on those guitars?

On the little Strat I use Gold Maxima strings. On the little Les Pauls, I use Black maximas, which are Teflon-coated. They don't make them anymore, but I had a lot of them lying around. The upper unwound strings are platinum-plated.

What modifications have you had done to your D'Mini Strate?

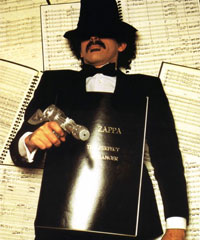

The neck and body are stock, and it has Seymour Duncan pickups, and a built-in parametric equalizer with variable "Q" [resonance]; that's the one with the concentric knobs. It was custom-designed here at the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen [Zappa's studio/workshop]. There's a volume control and a silver plug that takes the place of another parametric that failed when I was out on the road. It has a 3-way selector, and the toggle switch used to be for switching between the two parametrics. By having two parametrics, I was able to preset two different types of feedback boost. The circuit boards were worked on by Midget Sloatman and Eddie Clothier. David Robb, who was the guitar tech on the last tour, also did some work on it.

[...]

Do you collect guitars?

I don't go out and buy all the guitars all over the place. I'm not one of those kinds of guys. I do have a lot of guitars, but I don't know how I have accumulated them. I've got about 25 guitars. They just keep piling up.

Do you have top five favorites?

I've got the Les Paul that I use. It was a brand new guitar when I bought it. It's not a vintage thing. It was a very well made production-line Gibson Les Paul right off the rack.

You didn't go to the Gibson factory and have them custom-build one to your specifications?

You know, considering how long I've been playing Gibson guitars, I've never spoken to or heard from anyone connected with that company. There's no factory connection with Gibson whatsoever. I also have Stratocaster with a Floyd Rose installed on it. It was the guitar that I used the most on the last European tour. And the Hendrix Strat [a burned Stratocaster formerly owned by Jimi Hendrix; a detailed description is included in the Jan. '77 interview], which has a special size neck on it. It's an SG-size neck. It does certain things that other guitars won't do. The width and depth of the neck is different from that of a Strat, so you can do all kinds of things that just don't feel right on another guitar.

What distinguishes one instrument from another?

Each guitar has its own character and its own sounds that it likes to make, that come naturally to that instrument. So, I'm going to choose an instrument that matches the character of the song. I also have a Telecaster—one of the copies of the originals that Fender put out about a year ago. It's a real good blues guitar. The fifth guitar would be the SG copy that I got from this guy in Phoenix, Arizona. It says "Gibson" on it, but it's handmade, and it's got an ebony fretboard with 23 frets on it; it goes one fret higher than a normal SG. I play that a lot.

Do you use the 23rd fret often?

Since the cutaways on the guitar are so deep, it's very easy to get up all the way to the top. So, I can play higher on that one than on any of the other ones that I have.

How many guitars do you usually take out on the road?

On the last tour, I took out a Fender XII 12-string, the Telecaster, the Les Paul, the Hendrixx Strat, my old mirror-pickguard SG, and the Stratocaster with the Floyd Rose on it. Plus the mini Strat and the mini Les Paul. Right now, the only thing I miss on my D'Minis is the vibrato arm.

Do you use the vibrato that much?

On the last tour I used it to excess. Because the Floyd makes it possible to come back in tune after you go down to the subsonic regions. You can dump all the strings slack and come back up and be in tune. And the way my Floyd is set up, you can go down two octaves practically, then back up to normal position, and then bend up a whole-step and sometimes even a third. It's balanced so well that I can just wiggle it a little bit and get a real nice vibrato.

What kind of effect did you take out on the road with you on the last tour?

I took three MXR Digital Delays—two with minimum memory storage, and one with tons of it. I also used two MicMix Dynaflangers. I didn't have any fuzztones or octave dividers. I used three different amps—a Marshall 100-watt, a Carvin, and an Acoustic—and each has interfaced with a different digital delay. So I could store three different signals and get some weird sounds. For instance, you take your whammy bar and get some terrible tweezed noise, an store that. Then it would come out of the right, and another one would come out of the left one, and you could play over the top of it all. I've got a recording of that from the tour, and it's really an ungodly sound.

Did you take a pedalboard on the last tour?

My setup was pretty basic for that particular tour. You see, things don't always go according to plan here at the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen. A very elaborate digital setup that had been in preparation for about six months prior to the tour turned up a semi-fatal design flaw, which was allowing some digital grit to get into the audio path, just at the last minute as we were getting ready to pack up. And a lot of work on it had to be redone—and it still isn't as perfect as I would like to have it before I take it anywhere. That particular rack had some unbelievable features, because it allowed you to do presets of any combination of effects that you might want with preset levels to each effect and preset control to all the parameters. So, during the sound check, you could set one sound with a flanger and fuzz and an octave divider and bi-phase, and set all those parameters in a memory storage. And when you'd hit your switch, it would go exactly to that sound. With the use of a pedal you'd be able to cross-fade to any other preset using any other combination of devises that you had in the rack. It was a really great idea, but so far we haven't gotten it perfected.

You really put yourself at the mercy digital equipment on the road.

Well, I'm perfectly comfortable going out and doing a tour with nothing but an on-and-off switch on the amplifier. For much of the guitar I wasn't using the effects at all. The only one I would turn them on at all was when it deemed appropriate for some event during a solo. The guitar I played the most was my Strat with the Floyd Rose on it, and it was capable of such ungodly noises with that parametric EQ and the pickups that were in it. It made plenty of noises without any fuzztones or other crap.