1. No Not Now

We did a bunch of recording before we left LA [in September, 1981]. [...] There's a straight ahead mongolian sing-along song called, "No, Not Now."

Right now there's ten sides of new material that hasn't been mixed yet and we've been overdubbing on. And I don't know what I'm going to do with it because there's so much stuff. There's vocal and instrumental stuff. I have everything from really complicated orchestral-type things to a mongoloid rock and roll song called "No Not Now." It's Roy Estrada singing three-part falsetto harmony with himself. And all stops in-between.

On "No Not Now" there's an extremely distinctive bass line. Did you write it?

I just made it up. The bass part was done like this: Arthur Barrow came in to play bass, and bar by bar I would hum it to him. We'd play it, and he'd go as far as he could, and then he'd make a mistake, and then I'd show him the next part, and then we'd punch him in. And that's how it was done: like eight bars at a time. It's a wonderful bass line.

[...] I like bass lines. They're good, because for people who don't understand what's going on in the rest of the song, there's always the bass line.

Roy Estrada

Roy is now in a mental institution. If he's lucky, he'll be out in April [1980] and I'll take him to do some recording. But he's been there nearly 2 years . . .

I was in the studio when he was recording one of the songs from Drowning Witch. I don't recall the name of the song, but it has the line "but I like her sister . . . " with Frank singing. Well, in the studio that night it was Roy Estrada on that part. I had never heard Roy sing live, and I've always loved that Pachuco falsetto. It was so great! But it wasn't going all that well. Frank kept him doing it again and again. Gail came in for a minute and said that Roy really sounded out of tune. Frank had a shit-eatin' grin on his face and said "He always does, but the sound is incredible" or words to that effect. But when the album came out Roy was not to be found. It was Frank doing his low dumb-sounding thing, and it was, to me anyway (who had heard it done differently) a complete disappointment.

I like Roy Estrada a lot, but only met him fairly recently. Although I heard him recording No Not Now at Frank's studio, and thought he sounded great. But Frank replaced Roy's parts with his own voice—not nearly as interesting or fun. But then, neither is the song.

[...]

Frank had him singing "But I like her sister" in Pachuco falsetto over and over again. Gail came in and said "He sounds real out of tune". Frank said "He always does, but it's such a great sound!". I think he was just digging listening to Roy's voice. As I said, he never even used the track.

String beans to Utah

Utah is the most religiously homogeneous state in the Union. It is home to the Salt Lake Temple, and approximately 63% of Utahns are reported to be members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) which greatly influences Utah culture and daily life.

Donny 'n Marie

Can both take a bite

2. Valley Girl

"Valley Girl" (from Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch, 1982)—Fender Stratocaster guitar, 100watt Marshall amp.

"Valley Girl" started off at the end of an overdub session, just me on guitar and Chad Wackerman on drums. The tape sat around for months while I did a tour. Then I sat down and wrote some lyrics, and the tape sat around again.

"One day at a vocal session, I got out the track and had the guys in the band sing this chorale thing I'd written, so now we had guitar, drums and chorale background. A few days later, I woke up Moon in the middle of the night and had her come down and do a monologue. She did five separate ones, all of which I ping-ponged together to make the one version that's on the record. Finally, the bass was added last."

On "Valley Girl" there's some red-hot guitar way back in the mix. Why didn't you mix it up higher so that it could be more easily discerned?

Because it conflicts with the vocal part. And that red-hot-sounding guitar was just me and the drummer jamming at three o'clock in the morning. That track was the basis for the song. It was a riff that started off at a soundcheck about a year before, and I had been piddling with it for a long time. One night, we finally did it, saved the tape, and little by little we added all of this other stuff to it, and we got "Valley Girl."

The bass line was written later?

The bass line was never written. It was the last thing that was added to the track. The track didn't even have a bass part; it was just guitar and drums. And when Scott Thunes came in to do it, it was at a point where I thought if we left the guitar up high enough in the mix it would probably be thick enough where we wouldn't even need a bass. But the engineer, Bob Stone, said, "Aw, go ahead and put on a bass line." We were just about ready to go out and do a tour, and I brought Scott up to the studio one night after rehearsal. It took about an hour and a half, the same way as with Arthur Barrow on "No Not Now"—I said, "Play this: Boop, boop, boop," and he did it. He was playing the bass through a Vox amp, and that's what gives it that particular sound.

USA TODAY: What kind of point were you trying to make when you did the song "Valley Girl"—that fairly scathing approach to the girls in California? Is that the way your daughter Moon Unit was?

ZAPPA: Oh no. She's not like that at all. I wrote that song because that's what was happening in the valley at that time. You're the first person who ever thought it was scathing. Everybody else thought it was, "Oh, how cute. Well I'll act like that." So that will give you a rough idea of the intellectual comprehension of the average audience person. I mean, it is scathing. It is saying these people are airheads. These are their values. That's how they talk. It's a piece of journalism.

Moon Unit Zappa, "Like Father, Like Munchkins," Zappa! 1992, p. 23

I was in tenth grade when "Valley Girl" came out. I spent a lot of time back then going to bar mitzvahs. There would be all these kids out there whose lifestyle was so different from mine—this beer-drinking, rebellious, tortured existence, plus a funny way to talk that went along with it. So I would listen and pick up the dialog, the lingo, the information, everything. I was fascinated by it. I would do it around the house and make everybody laugh.

My dad spent so much time away touring that I just wanted to spend some time with him. And when he was home, he would work at night and sleep during the day, and we were up during the day and sleeping at night, so there never was much contact with him except when we passed each other in the hallways on the way to getting a drink of water or a peanut butter sandwich. So one day, I put a note underneath the door of the studio, since that's basically where he lived, and offered my services; that way, I might be able to spend time with him. And that's what happened.

He warned me that he was thinking about having me come downstairs to the studio, but the equipment had broken or something. So I went to sleep, but then in the middle of the night he woke me up and said, "Everything's ready." I went downstairs, and I panicked. I just kept talking. I must have done five or seven tracks, and he edited them together. At the last minute, he said, "I guess we're going to use it for the album." Next thing I knew, my father was away on tour, and I heard "Valley Girl" on the radio on my way to school. Throngs of students greeted me there. It was weird, because people I'd never had any contact with were suddenly interested. That was a great lesson, because you just never know who you're talking to and what's interesting about that person. It's good to pay attention all the time instead of having to wait until somebody finally does something spectacular. It's nice to feel noticed just for existing.

Since my father was on tour, I had the responsibility of doing all the promotion in the States for that album. I enjoyed that. It was fun and exciting. It was nice that people paid attention to me.

Guido Harari, "FZ And Me," Sonora, April, 1994

[Spring 1982] Then the invitation to visit the recording studio where Bob Stone "my computer"; is making "Valley Girl" (see the album Ship Arriving Too Late To Save A Drowning Witch) out of three different monologues by Zappa's daughter, Moon. "My relationship with Bob is purely professional", explains FZ glancing at the monitor of the telecameras which scan the outside of the villa every hour, "and it's better that way, I know nothing about him, where he lives, if he has a woman or what. Hello, goodbye and that's it, only a couple of breaks for a bite to eat and to go to the toilet".

Valley Girl Merchandising

After returning from your European tour, how did you feel when you found out that "Valley Girl" had become a big hit?

There are a couple of things about "Valley Girl!" being a hit: First, it's not my fault—they didn't buy that record because it had my name on it. They bought it because they liked Moon's voice. It's got nothing to do with song or the performance. It has everything to do with the American public wanting to have some new syndrome to identify with. And they got it. There it is. That's what made it a hit. Hits are not necessarily musical phenomenons. But as far as my feelings about it goes, I think that if that amuses Americans, well, Hey! I'm an all-American boy. And I'm here to perform that function for you. Since that time, we've hired a guy to make merchandising deals on that song. And you wouldn't believe what kinds of things will be coming out with the words, "Valley Girl" on them. You name it; everything from lunch boxes to cosmetics: including a talking Valley Girl doll in February.

SOFT PLUSH PROTOTYPE—EARLY 1980'S BY LJN TOYS

VALLEY GIRL SOFT PRINTED FABRIC APPROX. 13 INCHES WITH WORKING VOICE BOX AND VALLEY GIRL PUFFY STICKERS

IF YOU LIVED ON THE WEST COAST IN THE EARLY 80'S OR ANY WHERE IN THE U.S.—VALLY GIRL TALK AND LOOK WERE ALL THE CRAZE—THIS IS YOUR CHANCE TO GET A PIECE OF THAT SPECIAL POP CULTURE

(NOT FROM A SMOKE FREE HOME)

United Press International, January 13, 1983

Rock singer Frank Zappa has gone to court to stop production of a movie called "Valley Girl," which is the title of a hit song by his daughter Moon Zappa spoofing the speech of teenage girls.

In a suit filed Wednesday in federal court, Zappa said Valley-9000 Productions Inc. will be confusing the public about the source of the true Valley Girl name if it is allowed to proceed with production of the movie.

He is also charging the company with unfair competition and diluting his trademark and is asking whatever the court grants in general damages and $100,000 in punitive damages.

Zappa said if the movie is not stopped, his program of licensing the Valley Girl trademark for clothing, cosmetics, key chains, greeting cards, dolls and other products could be damaged.

Moon Zappa, Harpers Bazaar, April, 1998

My dad's music had made me shy, almost repressed about my own anatomy, with his lyrics about ramming things up poop chutes and shooting too quick—this, from my dad! He was so open creatively that I was off in search of black turtleneck bathing suits with long sleeves. "Valley Girl," the song my father and I did together in 1982, made me feel like a sad zoo specimen. Going through puberty in front of the world on shows like Solid Gold and Merv Griffin only added to my self-consciousness.

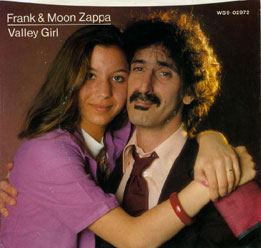

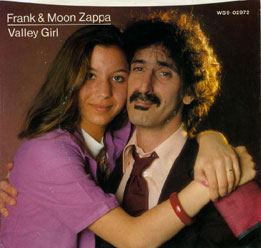

Single Cover Art

I think I was photographing Frank for a magazine article one night,

for a piece Dorothy Sirus was writing, and Moon just came in the room, and

she had her little purse in her hand. She was twelve then, or thirteen, and

she said "bye." And Frank said "Where are you going," and

she said "I'm going to the mall." I remember that. She was going to

the mall. I think I called her over, and she agreed, and I said "Come on,

cheek to cheek," and they got together. You can see the little pink wallet

in her hand, and she had her arm around him, and I took just a few frames. So

after the fact they said "Hey, this will make a good cover for this single."

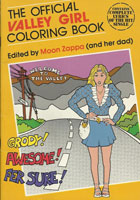

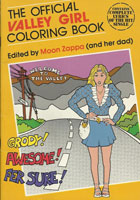

The Official Valley Girl Coloring Book

Paperback—October, 1982

by Moon Zappa (Author), Frank Zappa (Author)

It's like GRODY . . .

GRODY TO THE MAX

Slonimsky lives unknown in sunny Los Angeles in a modest bungalow with his cat, Grody To The Max, named in Valley Girl lingo by Moon Unit Zappa, rockstar Frank Zappa's daughter.

3. I Come From Nowhere

Well, I think that people who smile too much are dangerous. And that's a song about people who smile too much.

I very seldom play studio guitar solos. On the Drowning Witch album, the solo on "I Come From Nowhere" was a studio solo, and that was like two hours' worth of work to get a sound that I thought was suitable, and then about 20 minutes' worth of playing: punching in or doing a take and not liking it and wiping the whole thing, or fixing part of it, or just tweezing it up.

[...] On "I Come From Nowhere" there's a strong dissonance, like a minor second clashing in the first few bars. Is that guitar?

That is a bunch of bass harmonics a half-step apart. He's playing what I think is a little three-part harmonic chord.

What kind of guitar and enhancements did you employ for the solo about two-thirds of the way through that song?

It was the Les Paul played trough a Carvin amp. I think it's straight—no effects. That was just what it needed, I thought.

Did you record the rhythm track live and then mix in the solo and overdub parts?

Oh, no. Here's how that song started off. The original track was a rhythm box, and then the vocals were added—not the solo, just the orchestrational parts. Then the guitar solo was added on top of the rhythm box track, and the drums were added to play along with the guitar solo. The bass track was added last.

4. Drowning Witch

What guitar did you use on "Drowning Witch?"

I think both solos are with Hendrix Stat.

How did you get the feedback that pervades throughout?

It's live. Those were live tracks that were overdubbed. There are some equalizers in my guitar-parametric EQ with a little, narrow peak. And once you find the feedback range in the room, you can turn it up, and the guitar doesn't have to be loud to just feed back at that frequency.

Do you usually twiddle with it during a solo?

Yeah, first I set it during the sound check, and then if the acoustics of the room change due to the audience, I can just reach over and tweeze it while I'm playing.

How do you synchronize parts from different performances for final mixing into one song?

First of all, you start off with a band that is highly rehearsed, that maintains their tempo. They learn it at a certain tempo, then they'll play it the same way night after night. Do you know how much edits there are in "Drowning Witch?" Fifteen! That song is a basic track from 15 different cities. And some of the edits are like two bars long. And they're written parts—all that fast stuff. It was very difficult for all the guys to play that correctly. Every once in a while, somebody would hit the jackpot, but it's a very hard song to play. So there was no one perfect performance from any city. What I did was go through a whole tour worth of tape and listen to every version of it and grab every section that was reasonably correct, put together a basic track, and then added the rest of the orchestration to it in the studio.

Besides synching-up the rhythm, how did you deal with variations in pitch?

Do you hear any? There were no VSO [variable-speed oscillator, which controls the speed of the tape recorder] changes of the sections at all, because when we go out on the road, everything is tuned to a tune-up box every day. We have a standard: Everybody tunes to the vibes, because their tuning doesn't drift. We calibrate all our Peterson Strobe Tuners to them. That gives you consistency.