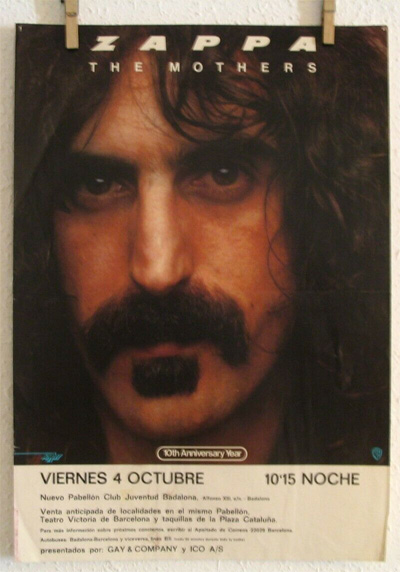

The 10th Anniversary Tour

Napoleon Murphy Brock

FZ, April 20, 1974, interviewed by Bill Gubbins, Exit, May, 1974

Napoleon has vast problems with that Freak Out material because his learning rate is slower than most of the guys in the group, especially in terms of words. He picks up the instrumental parts really fast.

We rehearsed six hours a day, six days a week for two weeks before we came out here on nothing but that Freak Out stuff. And he still doesn't have the words memorized. He's really struggling with it. I got on his case after the show tonight. I told him if you're gonna play something that nobody's ever heard before and make a mistake in the middle of that, 2% of the audience will know you blew it. But if you go out there and you're singing songs that are already on record and people know what the words are, I don't want anybody in the audience to feel sorry for you. So get out the cassette machine and learn those words.

But he really tries, you know. He's the most unusual guy that's ever been in he goes into his room after a show and gets out a cassette machine and the stuff that he's supposed to work on, which is the flute part or the sax part, and he practices. At night! After the show! He practices on his days off, sits in there for four hours, five hours and goes over the stuff.

Albert Wing

Albert Wing, interviewed by Fred Banta, February 17, 1998

I'd known Frank for quite a long time through Bruce and Tom [Fowler]. Originally I'd auditioned for Frank's group back in '73 or '74. And actually he said that I had the gig. [...]

And I auditioned on the "(Bebop) Tango" and played the "(Bebop) Tango" for him, and nailed that. And he said, "Wow, pretty impressive." Then I waited around for a half hour at the Sunset studios where they were rehearsing. And Frank came back and said "Sorry about telling you you're in the band, but we really can't afford you right now, you know." I don't know what all that was about, but I guess he'd had a meeting with his management, but he'd already had a sax player anyway, Napoleon Murphy Brock. So I guess they were looking for something else cause eventually he got Don Preston and Walt Fowler to do the gig, so I felt it was probably just a combination of a horns thing because if he already had a sax player, why have me, you know?

Walt Fowler

Walt Fowler, Facebook, January 11, 2015

[FZ, unidentified trombone player, unidentified, Albert Wing, Walt Fowler]I had the opportunity to be heard by Frank Zappa when I was 18...a month later, I joined my brothers Bruce and Tom and became a Mother of Invention and went on my first pro tour. And so it began...

Don Preston

Don Preston, interviewed by Phil McMullen, Ptolemaic Terrascope, Summer 1993

He then got another band together with George Duke, the Fowler Brothers [Tom and Bruce] and Ruth and Ian Underwood—and I went on tour with them throughout the United States, also did the album Live At The Roxy with that band. That was the last time I was in the band, I finally had a falling out with Zappa and couldn't do any more.

Andrew Greenaway, "Don Interrupts—Interview With Don Preston," The Idiot Bastard, February 18, 2001

IB: And your recollections of the 10th Anniversary tour?

DP: I mostly remember how great the band was and getting to know George Duke who was an exceptional musician.

John Smothers & Other Bodyguards

Ed Baker, The Hot Flash, May, 1974

Sitting nearby us was a black gentleman, about six-foot three, 200 pounds, powerfully built, with a shaven head. I think he was Zappa's bodyguard, although that may not be his official occupational title. Some kids were climbing onto the stage over to the left where Don Preston was. Suddenly he was there. He jerked his arm swiftly as if to say, "Down and away from there and I mean it!" They got down.

FZ, interviewed by Den Simms, Eric Buxton & Rob Samler, "They're Doing the Interview of the Century—Part 3," Society Pages (US), September 1990

[Marty] Perellis know Smothers from Baltimore. Perellis is also from Baltimore. When I first started carrying a bodyguard, I had tried out two . . . let's see . . . no, I had three bodyguards before Smothers. The first one was a guy named Newmar, who lost the job because on one occasion, he took a fan, who'd tried to jump onstage, I mean, some menial little transgression, and took him out in back of the place, and beat him up, (laughter) and, y'know, I thought, "This is totally uncalled for." [...] So, he got fired. Newmar was an off duty LAPD, and then, the next guy was another LAPD, except he was a Jehovah's Witness [...] and when you have to spend a lot of time with these guys . . . and I couldn't handle that guy y'know. He didn't last long.

Then, another guy, who was really a great bodyguard, and I wish I could remember his name, he was only with me for a short time, but he used to sing in a rhythm 'n blues group called "The Calvanes", on Dootone, and he recorded a song called "Florabelle", which I have in my collection. His name is Bob. I can't remember his last name. Bob was a good guy. We used to sit in the dressing room, and sing doo-wop tunes together, but he wasn't available anymore, and couldn't do it anymore.

And then, I got another guy named . . . John, who was the brother . . . of a girl that I went to high school with in Lancaster . . . and he contributed a little folklore. He was the one who cane up with 'swimp', and, uh . . . [...] Well, there is a language called Gullah. [...] Gullah is that black dialect, that Negro dialect that is repeated most constantly. It comes from this language called Gullah. They have different words for different things, and different pronunciations and 'swimp' is 'shrimp'. They call 'em 'swimp'. His language was very Gullah, and so, I was introduced into the concept of 'swimp'. The other thing that guy was famous for was he liked to fuck Holiday Inn maids with hairy legs. [...] And, the idea that, uh ... y'know, to imagine this guy in the morning, when the maid knocks on your door, and you have to get up too early, and he would be dragging one of these women into the room, and, y'know, strapping her on before he got on the bus, and telling everybody how hairy her legs were, scratching his back, and all this weird shit. (laughter) Quite a guy.

Then, along came Smothers. At first, at the beginning of the tour, he thought I was crazy. He tried to go home. He tried to get out of the job. But, he stayed with me for ten or eleven years.