The Early 1973 Band

Frank has now fully recovered from the attack on him by a somewhat crazed lunatic while touring Europe. He is anxious to forget about those days and those Mothers. He is pretty bitter about Volman and Kaylan and understandably so. After forming Phlorescent Leech and Eddy (with Aynsley Dunbar and Don Preston) they turned around and repeatedly stabbed him in the back in the press. After that experience Frank said he was never going to put together another "permanent" band because of the general unreliability of musicians. Instead he intended upon putting a band together for each album do a tour and then break them up and start again. This set of Mothers was to be the first of those "temporary" bands, but they were so happy with each other that after one tour they decided to make it two, and now are going on their third tour with plans to stay together permanently.

Then there are other people I'll hire for the group, and I'll audition them and I'll say, 'all right, I think this musician is good,' but you take them on the road and you find they can't handle it.

Like, for instance, there was a singer that I hired one time who did three days. The first day he was fantastic, the second day he started going down, and the third day he was in trouble. One day at a hotel he ran up a bar tab of $90 for himself. I didn't know he was an alcoholic before I put him in the band, so I sent him home right in the middle of the tour. You can't always tell.

Craig Steward

COQ: Who is in your group now?

Zappa: Ian Underwood from the Garrick Theater. Ruth Underwood on marimba and percussion. George Duke on piano. Jean-Luc Ponty on violin. Ralph Humphrey on drums, Bruce Fowler on trombone. Tom Fowler on bass. and we're trying out a harmonica player named Craig Stewart.

The ['73] audition was established when FZ heard me in a club in Wichita, Kans. my home town [note: according to the Frank Zappa Gig List, FZ played in Wichita, KS, on November 30, 1972]. He invited me up on the stage which was featuring my friend's band called Bliss. We played a slow blues in the key of A and afterwards he said he would be flying me out to LA to audition. He had [?] Smith, Ponty, Duke, Underwood's, Fowler's and others at that audition. I really wasn't able to play ensemble work as I had only been playing 5 years. After 3 days FZ called me over and asked me what I thought and I said Frank I think I should go back home. He graceously smiled and said I think you are right! Please don't think of this as being a failure. You go home and practice, call me when you feel you are ready. [...] I went home practiced 5 years, called him back and he flew me out to record on Joe's Garage Act I. Thus began a 3 year studio session relationship with the Zappa's plus I trimmed their trees on several occassions. I performed live with FZ in Wichita [April 11, 1980] and the Santa Monica Civic Center when FZ had Steve Vai with him [December 11, 1981].

Well, on the third day of my audition for the Roxy band, Frank called me over and asked what I thought. I told Frank I thought I should go home! He swayed back a bit and said he had never heard anyone say that before. He said, "I agree with you, but don't consider this a failure. Just go home and improve to where you can understand better what I need you to play." I said, "Frank, it is no failure to me. It isn't every day a tree trimmer gets to jam with you, Ponty, George Duke and company!" I had only been playing harmonica five years and I could only play blues and, as Frank shared, blues in a unique way. I went home and practiced and played with a guy named Donn Salyer who really helped mentor me. [...] Frank also asked me at the end of that audition how much I made a day trimming trees. I said, "$50." He told Steve Auerbach to cut me a check for $150.

[...] On my original audition with Frank I approached the rehearsal studio and heard this Hendrix sounding electric violin—what in the world! I had never heard of Jean-Luc. I went up to him, as he was on stage all by himself practicing as the other artists had no yet arrived. I told him I loved what he was playing and that it was amazing! He answered very thankfully with a heavy French accent. I spoke a little of my basic broken French to him and I think he was touched by my effort. When the whole band got there for rehearsal, Frank had me come up to the stage and had a mic and a basic amp for me to play through. We played "King Kong" and I followed Ponty's solo. I did a pretty good job without my own rig and Frank was pleased. After practice or a break, Jean-Luc invited me to go to a cafe for a sandwich together.

Ian Underwood

During the last period of time when I was with him, I was actually playing woodwinds more than anything else, but before that I played a lot on Hammond organ and ARP 2600. We never really used the synthesizer that extensively, though. It was either just for solos or to play a given line that could have been done on clarinet or something else, so whatever sound we used on it wasn't a big issue. In fact, I never thought about keyboard sounds at all.

George Duke

When I went back with Frank, back in '73 when Jean-Luc joined the band, because I left Frank for a couple of years and when I was in Cannonball Adderley, I had to do the jazz thing for a couple of years. But when I re-joined Frank in '73, when Jean Luc came in, I said "Frank, I'll join on one condition. That I will not have to play that damn trombone!" (laughs) and so Frank said "Okay." And that was it.

And they didn't need me to play trombone. They had Bruce Fowler.

Waka Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo were jazz records, but Frank wouldn't admit it. I'd say, "Frank, you're playing jazz." He'd say, "No I'm not." That whole thing led to his well-known saying, "Jazz isn't dead, it just smells funny." One reason I went back with Frank from Cannonball was because he'd hired a bunch of jazz guys that I'd worked with, like Ralph Humphrey, the Fowler Brothers [Tom on bass and Bruce on trombone], the incredible percussionist Ruth Underwood, Jean-Luc Ponty, and Sal Marquez, who's a great trumpet player.

Frank was the first person who said, "Hey man, you oughta start playing synthesizer," I said, "Oh man," you know because all I'd heard was, you know I took a synthesizer class at school, and I said, "Nh-hum." But I got into it, and you know, I talked to Don Preston about it, and he says, "Yeah man, here's some things you can do with it," so I got into it, and I began to like it, and I began to humanize it for me, the whole point of playing synthesizer to me was to make it sound like it was coming from me. You know, not like it was coming from somebody else, or a machine.

Jean-Luc Ponty

Jean-Luc Ponty, interviewed by Alain Le Roux, Le Jazz, July, 1997

That was the second time we worked together, and it was based on a misunderstanding. Zappa had asked George Duke to join the Mothers of Invention. But George felt kind of lonely among all those rockers, and he left Zappa to go with Cannonball Adderley. He passed through Paris with Cannonball, and told me a group was being put together in Los Angeles and his manager wanted me to be part of it. George told me, "If you accept, I will too." But I hadn't understood it was to play in Zappa's group. In the end I found myself in Los Angeles, touring with Zappa. It was again a very interesting experience at the beginning, because Zappa took out all the very complex instrumental music that he had stashed in his desk for a long time since it was too sophisticated for the previous members of the Mothers. He had written music that was very influenced by Stravinsky, so he wanted to put together a group of excellent instrumentalists. But the public lost interest quickly, and he had to go back to satire and more commercial rock. That wasn't what I wanted to do, so I left after only seven months. He didn't take it well at all and we parted on very bad terms.

Jean-Luc Ponty, interviewed by Thierry Quénum, jazz.com, September 6, 2008

He hired me along with George Duke in his Mothers of Invention because he wanted high-level musicians to play his instrumental music. But things didn't go as well as I expected: in fact we never played any themes from King Kong live. Zappa played to huge audiences and I think he was prisoner of his own image. His fans wanted songs, not instrumentals, and I wound up accompanying songs and playing only one solo per night. So I quit.

[...] Even if the last moments with Zappa were not satisfying, playing with him helped my vision of music evolve a lot. It was the same with Mahavishnu. I came from the classical tradition and had switched to jazz, but jazz at the time was still very much influenced by bebop and the lyrical compositions I had started to write in Paris at the end of the sixties didn't fit with these square bop structures. Besides, in Europe, I had started experimenting with rock musicians who were interested in jazz and jazz musicians who were curious about the new technologies. So playing with Zappa, then McLaughlin was relevant: they were experimenting with wah-wah pedals, phase shifters, ring modulators and this brought me to electrify my violin and be able to try these new technologies, just like a guitarist. What's more, the type of jazz rock I experimented with Mahavishnu allowed me to use my knowledge of classical music. The musical structures that Zappa and McLaughlin were using helped me get rid of the bop and standards tradition and let me follow whatever came to my mind.

Tom Fowler

Tom Fowler is the brother of Bruce Fowler, former trombone player with The Mothers. "We had another bass player for a while, and he couldn't cut it, so Bruce said, 'my brother can do it.' He brought him in from Salt Lake City."

Bruce called me up and I auditioned for Frank and somehow I got the gig. I hadn't even been playing bass, but I guess he got sick of looking for a bass player. This was in 1973. The audition was very simple. He had me play a couple of odd muted things and groove for a while, and then he said 'OK, you're it'.

Kin Vassy

I'm doing them mostly, and that guy [Kin] has just been added to the group. That was the first time he's been on stage with us (tonight). That was completely unrehearsed; he's never even been to rehearsal with the group. He used to sing with the First Edition and the New Christy Minstrels. He's going to be singing on some of the stuff and so is Sal (Marquez, trumpet). Why we might even have George singing on some of it, but I'm doing the lead vocals.

Then there are other people I'll hire for the group, and I'll audition them and I'll say, 'all right, I think this musician is good,' but you take them on the road and you find they can't handle it.

Like, for instance, there was a singer that I hired one time who did three days. The first day he was fantastic, the second day he started going down, and the third day he was in trouble. One day at a hotel he ran up a bar tab of $90 for himself. I didn't know he was an alcoholic before I put him in the band, so I sent him home right in the middle of the tour. You can't always tell.

I think this was Kin [Vassy]. The First Edition's drummer Mickey Jones has an autobio with samples available on Amazon where he mentions Vassy was a great singer and good guy but also a heavy and violent drinker.

Sal Marquez

What sticks out most was the departure of our trumpeter, [Sal Marquez]. You can see him in the video, trumpet and trombone. One tour was more than half over. One day he thought Frank was back at the hotel, and was walking across the stage smoking a joint. Frank appeared, blocking his path. He said (paraphrasing) You know the rules. No drugs. You're Fired. We'll fly you back to LA on the first plane. This news traveled fast and soon we were all saying our goodbyes. Everyone was sort of stunned. It was hard to imagine how the sets would work without this musician. But soon Ian was covering many of his parts. And it kinda limped along to the end.

Keith (aka Bazza Keefer aka James Barry Keefer)

The 70's were awesome!!! My family and I moved to Southern California as I was recruited to sing lead for Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention. What a great man and what a great time for me !!! I did that until the mid 70's where at this point I spent most of my time writing and performing locally and at the same time helping to raise a family.

In the 1970s, he toured with Frank Zappa and also recorded one single "In and Out of Love," for Zappa's Discreet label.

When he got out [of the draft], Keith did some independent recording and joined Frank Zappa's 1973 touring band, trying to inject some Philly soul into toilet-joke tunes like "Don't Eat the Yellow Snow." "I think they brought me in to commercialize Frank," says Keith.

Geo: I understand that you were part of Zappa's touring band in 1973. How did you join up with Frank? How was this tour?

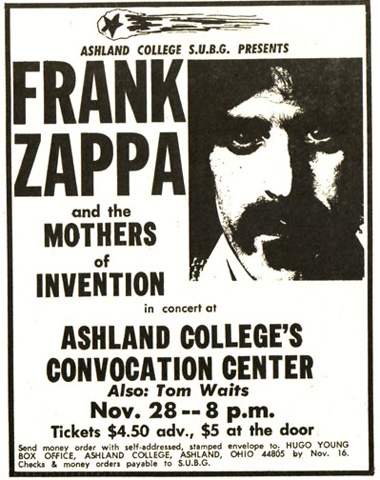

Keith: The Vice President, and dear friend, of my management in N.Y.C (Lenny Stogle Associates) Zack Glickman, had left and gone to the West Coast to work for Herb Cohen .He managed Linda Ronstadt, Tom Waits and Frank Zappa. Zack brought me into the band when Mark and Howard (of The Turtles fame) left to do their own thing. It was a blast working with the likes of Ruth and Ian Underwood, and a baby George Duke and the Fowler Brothers and of course Frank. He was a wonderful man.

Question 24 John Asks: Hi Bazza! I collect music memorabilia and recently acquired a cancelled check that Frank Zappa wrote to you (on his Discreet Records account) for $20 dated 3-22-74. What were you working on in March 1974, and do you have any idea what the check was for? [...]

Hello John, I would believe I was issued that check while I was on tour with Frank and the Mothers when I was singing lead for the group. I was brought aboard after Mark and Howard ( of the Turtles and Flo and Eddie fame) left to pursue their own careers. [...]

Question 33 Soulbraker Asks: Are you on any of Zappa's commercially released recordings?

Hello Soulbraker, Unfortunately, I didn't. He did however sign me to his label, "Discreet Records" where I recorded and released a series of singles.

Well at that point around the early 70's I was good friends with

a gentleman named Zack Glickman, who was vice president of Frank Zappas label. And handled Linda Ronstadt and Tom Waits and I relocated out

here in L.A. and Zack said I want you to come out, Mark and Howard are leaving

Frank Zappa, I'd like you to come out and sing lead for the mothers of invention. So I packed up my family and moved out here in 72, and hung and

sang with Frank all over the country, performing songs like "Don't Eat

the Yellow Snow".

Bruce Hampton

In 1973, Bruce [Hampton] heard that Frank Zappa was holding auditions for a vocalist. He quit the band and went to California to try out, but didn't get the job. Although I was disappointed when Bruce left, in retrospect I'm glad he did. The band broke up as a result of his leaving, and had he stayed we probably would have made a second record. To be honest, if we had recorded at that point in time, I don't think it would have been very good. I'm glad that Music to Eat is left on its own to represent the times that the band shared. We were all incredibly lucky to have run into each other when we did.

April 27-May 20, 1973—US East Coast Tour

Steven Desper—House Mixer

Charles Ulrich, June 8, 2015

During the intro of 4/27/73 Princeton, FZ refers to "Steve, who is our new mixer. First night for Steve." They had just had eighteen days off, so that's a plausible date for Steve Desper to start working. FZ addresses him again on 4/28/73 Philadelphia (as "Steve Desper"), 5/1/73 Kent, 5/4/73 Toronto, 5/73 unidentified location, 6/24/73 Sydney ("that little guy back there, who's running the sound. Steve Desper, ladies and gentlemen, lurking off in the distance, taking care of the noises for us, as the lights converge on Dwarfland"), 6/25/73 Sydney ("Mr. Steve Desper"), 6/28/73 Melbourne, and 7/8/73 Sydney.

[Kerry McNabb is] the third mixer this band has had—the first one was Stephen Desper, who's worked with the Beach Boys. I bought half their PA, and he came along to mix it—but he resigned because it was against his religious principles to be on stage with a band that sang our kind of lyrics. He eventually decided to quit showbiz, and went into a Christian Science college, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Around the time of [Beach Boy's] HOLLAND, American Productions (owned by the Beach Boy Corporation) sold the double-set large & powerful sound system(s) that I had designed and they had put many shows on with all over the world. The house studio and equipment was to be dismantaled. New equipment was bought or built by engineer Moffett for the new Santa Monica Studio. The sound system, including its four consoles, 16 MacIntosh 1000 Watt amplifiers, 32 JBL speaker systems (2x15" low-end + phenolic dome mid + bullet high-end), and two Phillip effects devices, 60 mics, booms, 5000 feet of Neumann microphone cable in 25 and 50 foot lengths and a moving van full of custom-built Anvil travel cases were all sold to Frank Zappa Productions. He wanted to incorporate it into a more elaborate traveling system for pending worldwide tours.

I was not interested in traveling to Holland to make an album and Mike [Love] wanted to hire Moffett because he meditated and I did not. When the Beach Boys left the country and tore down the house studio, Zappa hired me to put together his sound system and mix for him on the road (and studio) for the next several years. That was the Zappa band with George Duke, Jon Luc Ponty, Ian Underwood, etc.

FZ interviewed on WABX, Detroit, November 2, 1973

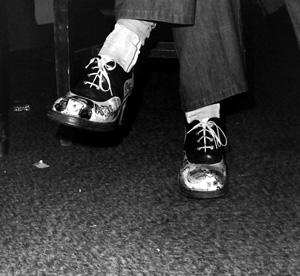

[Over-Nite Sensation's cover] foot represents the foot of Steve Desper, who used to be the sound mixer for The Beach Boys, and who worked for us for two tours, one in the States and one in Australia. He quit working with The Mothers because he was offended by the lyrics, and decided that he was quitting showbiz altogether, and he entered a Christian science seminary in Boston . . . he's a very upstanding gentleman.

What a fantastic tour that was to be the house mixer for all the US and Australian tours with the such outstanding musicians. I still have all the show mixing notes and music for the shows indicating mixing cues and gain changes. There was never a moment to loose consentration—an intence show to mix, but the music was very rewarding. It was ten times more demanding than anything the Beach Boys were doing on the road. We brought out 362 lines from the stage, each representing a sound source. Those went into preset sub-mixers before coming to the main mixer. Sound checks could easily take two hours. Zappa demanded nothing short of perfection from his band and from me. I learned how to hear in the present time while mixing (or setting up changes) in future time. Most of the time I was about ten beats ahead of the band, ready to execute the changes on the beat.

[...] I recorded every show on a pro-cassette recorder for my own record. Some kid stole all the tapes from my house years later, and by the time I retrieved them, he had used most of them to re-record disco music from the radio. I still have a few complete shows left. The sound is incredible.

The first and immediate demands falling on me were for selection, connection and maintenance of the touring system. When combined with the original American Productions system, the total touring system was mostly expanded to accommodate all the instruments on stage from the band. Otherwise there was plenty of power and speakers for any venue on the booking. I bought several—maybe six or seven—additional consoles of 25 to 50 inputs each. These consoles were mounted vertically to the walls of the sound truck for domestic tours or transported in cases that remained unopened but vented for international tours. You see there were over 350 independent sources of sound coming off stage. These sources were sub-mixed in their respective consoles before being sent to the house mixing console. For example, Ruth's vibraphone had a mics permanently affixed so as to pickup the sound of each of the bars making up the entire vibraphone. These were all balanced, EQed and pre-panned in the vib-console. The house mixer got a two-channel feed. The drums were all close miked, including each cymbal. These were all balanced, EQed and pre-panned in the drum-console. The house mixer got a two-channel mix of all drums except the kick(s) and the snare. So four feeds came to the house mixer of stereo drums, snare and kick. Another console handled all of George Duke's synthesizers with a two-channel mix sent to the house. Same true for the brass section. The acoustic piano used a Countryman custom pickup that spanned the entire width of the piano. In essence, each piano string has a coil pickup (same as used on a solid-body guitar) over it. And, they all had to be balanced and panned. The reason for using pickups rather than close miking with several microphones is that with the coil pickups there was absolutely no acoustic leakage from the other instruments that might wash-out the sound of, say the drums or guitars. Since every instrument was close-miked or picked up by a coil, it meant that stage monitors could operated at a very high level without feedback worries. This is before in-ear monitoring was even heard of. Frank hated feedback. Only once during my time with him did some source get out of control and ring. Frank stopped the show and articulated me a new asshole for the enlightenment of the audience and the band one night when he heard the ringing. It took about five minutes of testing to figure out what of the 350 inputs was the culprit, but to credit his desire for perfection, Frank was the type of guy who would not settle for second best. Nope! He stopped the show and had the problem fixed. Then restarted the song from the beginning—and proceeded with the sound as it should have been. Frank knew how many cues I was dealing with and that I would have no time to contend with the ringing . . . which would only mean that some cues would be missed if I tried to fix it on the fly. With a show this complex, if you want it right you have to stop and fix the problem. So with Frank there were second takes in concert. If the band came in late for a cue or they were not all together for the downbeat, in other words were not playing tight enough for him, he would stop the song right during the show and demand that a player or players pay attention, then start the song again. If you were a member of the audience he was going to make certain that you got a good performance that night. No mistakes allowed. Only re-starts.

Somewhere in my storage of things related to Zappa are the mixer's cue sheets for all the songs in his concert repertoire. These are the bars in the score of each song where a change in level or signal routing is required. These changes come along about every other bar or measure, but sometimes there were two or three cues within a measure. Believe me, I was a busy fellow—no time for just sitting and listening. You need to know how to read music to mix for Frank Zappa.

April 29, 1973—Rec Hall, Penn State University, State College, PA

Daily Collegian, April 30, 1973

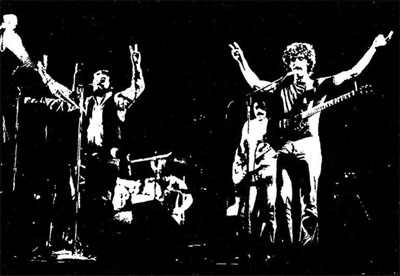

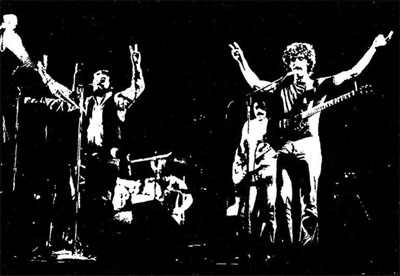

Photo by Randy J. Woodbury [Sal Marquez, Kin Vassy, Ralph Humphrey, Tom Fowler, FZ]

May 11, 1973—Milwaukee Arena, Milwaukee, WI

[Jean-Luc Ponty, Bruce Fowler, Ralph Humphrey, Ian Underwood, Tom Fowler, George Duke, Sal Marquez, FZ.]

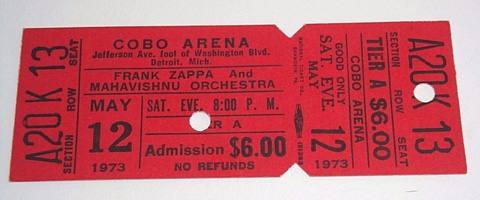

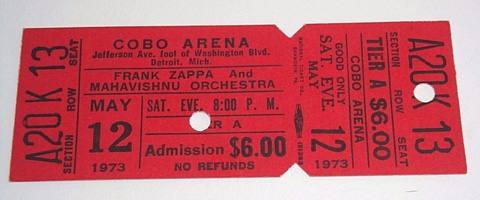

May 12, 1973—Cobo Hall, Detroit, MI

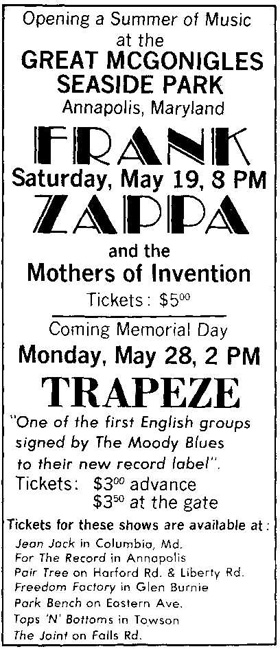

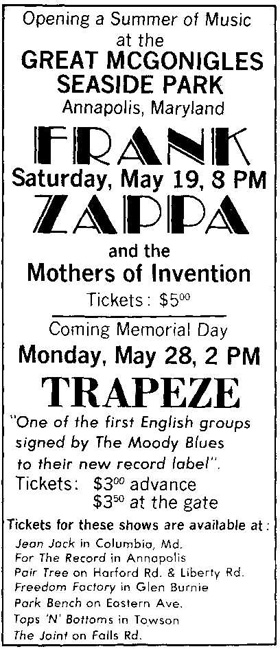

May 19, 1973—Great McGonigle's Seaside Park, Annapolis, MD

1973—DiscReet Records

DiscReet, according to Zappa, its president, is not an extension of the old Straight/Bizarre labels. "Those," he says, "were two labels for two different kinds of product. This is one label for all different kinds of product, an independent distribution deal on more favorable terms with WEA and for more dollars."

Q: What kind of contract do you have now?

Zappa: We've just negotiated a new one for about four or five years.

Frank Zappa and his business partners, Herb Cohen and Zach Glickman, have realigned their Bizarre/Straight Records Warner Bros. custom label operation to the new title, DiscReet Records. Warner continues worldwide distribution.

According to Bob Glassenberg, newly-named general manager of DiscReet, the change was made because Zappa's former label titles do not lend themselves to commercial support of upcoming releases. Glassenberg was former WB campus promotion director and Billboard campus editor.

Other new DiscReet staffers are graphics director Calvin Schenkel and press coordinator Kathy Orloff, both former freelancers.

DiscReet is planning eight album releases during its first year of operation. All future Frank Zappa LPs will be available on quadrasonic disks. Scheduled for this month are Zappa and the Mothers of Invention with "Over-Nite Sensation" and Tim Buckley's "Sefronia." A solo Zappa LP will be out by Xmas.

How do you choose the people who play on your label, on Discreet?

Well, I haven't been choosing them. You know, from the time that Bizarre and Straight, which were the first two labels that I had, and the time that contract ran out, I sort of decided that I was going to spend my time working on just the Mothers stuff, rather than producing other acts. Because when you produce a record for somebody else, here's what happens. If it doesn't sell, they tell you it's your fault. If it does sell, it's your fault cause it didn't sell more. And so you can't win. And when you figure it takes anywhere from 2 to 3 months, to really do an album right, I don't have 2 to 3 months out of the year to produce somebody else. Last year, we toured 7 or 8 months, you know. And the rest of the time, I sorta like to relax, you know, and part of that time that I'm not on the road has to be devoted to working in the studio with the Mothers stuff. So I just have shyed away from outside production. Anything on Discreet has been Herb's choice.

Erik Gerritsen, "Frank Zappa," Hot Licks, December, 1975

When Bizarre's contract expired in 1973, Zappa renegotiated a new label arrangement with Warner's, and Discreet was born.

June 15-July 8, 1973—Pacific Tour

Barry Leef

Bakery's brilliant vocalist Barry Leef is rehearsing with Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention and will probably return to the United States with Zappa as the new Mothers' lead vocalist.

[...] The big break came for Barry two and a half weeks ago when Bakery did a spot at Sydney's Chequers Disco.

[...] Fate walks strange paths and Mr. Frank Zappa chose to walk into the disco just as Bakery moved into a set of three numbers by Zappa and the Mothers.

Normally, this would be incredibly embarrassing to any group in the world—Zappa doesn't appear to be the sort of person who would enjoy seeing some other band playing HIS music. But the bizarre maestro sat through the whole performance and then went backstage to introduce himself.

He just came up, stuck out his hand and said—"Hi, I'm Frank Zappa, I was knocked out by your set," Barry told me.

"We all just about passed out."

Zappa didn't leave it there. He arranged to see Bakery again and invited the group to his concerts as his guest.

[...] He arranged an audition for Barry with the Mothers of Invention in Sydney last week then, out of the blue, asked if he would come to Melbourne and rehearse with the Mothers in preparation for a return concert in Sydney next Sunday night (July 8).

Barry didn't hesitate—he jumped at the chance.

If Zappa is completely happy with Barry's performance, he will join the Mothers of Invention as lead vocalist and return to Los Angeles with the band.

[...] But he has no illusions about joining the world's most famous experimental rock band. "If Zappa can hire me as spontaneously as he did, he wouldn't have a second thought about firing me just as fast if I didn't come up to his standards," he said.

June 24-26, 1973—Sydney, Australia

Zappa: The hardest thing about what we do is trying to make all of the electronic equipment that we use on stage work every time we set it up. There are 302 sound sources on stage that go through 302 wires out to a mixing board out in the audience, and every time you play some place you have to set it up and make sure everything is working. Sometimes that will take you four to six hours before you have to come back that same night and play a concert and that's hard.

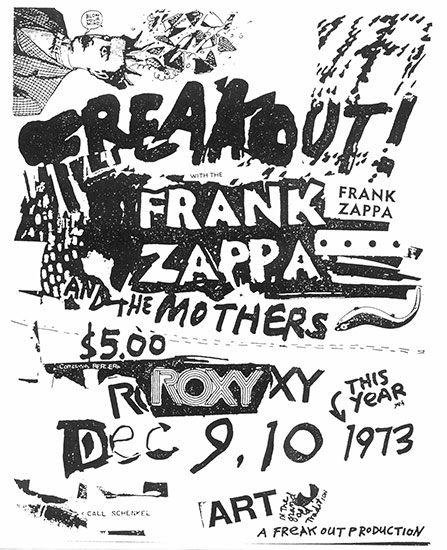

We're recording a live album here in Australia and we had three very good nights in Sydney where everything seemed to work and everyone was playing very good and I think we're liable to come up with something that sounds even better than the Fillmore album out of this tour.

June 28-July 1, 1973—Melbourne, Australia

Zappa: We have some Australian crew people helping us out but the guy who is actually doing the mixing for the show is from America. His name is Steve [Desper] and he used to work with the Beach Boys. We've made arrangements here in Melbourne to use a 16-track facility and there'll be an Australian engineer who'll be mixing for the tape.

Ian [Meldrum]: Will that be John French from T.C.S.?

Zappa: I don't know what his name is. That sounds right to me though. He'll have to be good to get this show down on tape because it's complicated.

Ian: Will it be for world-wide distribution?

Zappa: Yeah. I think the stuff in there is of sufficient interest that people outside Australia might get off on it.

June 28, 1973—Melbourne

At the heels of concert one in Melbourne came the yapping Vice Squad.

Slinking backstage, maybe hoping to free some of the entourage with an impromptu dope-bust, they merely left the scene with a few warning snarls and empty jaws.

It was an audible "motherfucker" which conveniently loosed their leash; though deep suspicions were held as to how come the VS were at a goddam rock concert in the first place. And funny how Truth got hold of the story so fast.

"Yer not in America now, boy" added besuited VS heavy to Numbar [Nagnew, FZ's bodyguard], who just happens to be black. Ooo-woo.

Zappa freaked (he doesn't use dope, but is human), switched rooms, reregistered under the name of Steven Teech (pr. as in Yeech), and grabbed a no-elbow-room dinner at the Distillery a go go, well-fancied by autograph hunters and DJ's.

June 29, 1973—Melbourne

Auditioning Ausvocalist Barry Leef, fresh from Bakery, stepped onstage at Zappa's request to blast the crowd with a high-voltage rendition of Road Ladies (plus), which shook with confidence and energy.

"I just wanted to see what he'd do," said Frank. "He did awreet."

This time no Vice Squad, more groupies. A rose and a note for Zappa from the audience. Merry promoters in the dressing room, goo-goo-eyed girls out the stage door.

July, 1973—Hawaii

I took [a vacation] once. Back in 1973, on my way from the Australian tour, I thought I needed a vacation, so I reserved a hotel in Hawaii for two weeks and brought my wife and children in. But a week went by, I cut short the vacation and came home, because I got so bored that it nearly drove me crazy.

IB: So how did the meeting with Frank come about?

NMB: As I understand it, he had just finished touring Australia, and they were getting ready to go to Europe a week or two after that. And he was taking a little break with his wife, Gail. They stopped off in Hawaii for a week or so. And his road manager, Marty Perellis, set them up in a hotel and went out walking around in Hawaii—probably to see if he could get lucky or something! If you want a good time, what better place to do it than in Hawaii? Hawaii is literally paradise. And he came to a show of mine—outside a nightclub at the Coral Reef hotel—and got curious as to why there was a line of people waiting to get into a place on a Wednesday night. He didn't recognise the name of the band, so he thought he'd get in line and come in and see why everybody was queuing up.

IB: What was the name of your band?

NMB: Gregarious Movement . . . [...] Mostly the music that we were playing was happy music. Anyway, he came into the club and saw us playing—didn't recognise us, because no one knew about us except the club owners that hired us and the people who came to see us. He ran back to the hotel, woke Frank up and said, "Hey, get your clothes on: I just found your new lead vocalist." Because Frank had just fired Sal Marquez—they'd had some sort of squabble in Australia and he was without a lead vocalist, because Sal was the lead vocalist at the time. Frank got up, came by to the hotel, stood in line like anybody else and once he got in he sat at the back of the room—there weren't any seats. We were quite popular there, because we were a band from the mainland. [...] During one of the intermissions, Marty Perellis walked up to me and said, "Someone wants to meet you." And I said, "Well, I've only got 15 minutes. Is it important? What's it about—you want to hear songs? Tell me which song you wanna hear and I'll play it for you." And he said, "No, he actually wants to meet you." And I said, "Who is it? I only have 15 minutes." He said "It's Frank Zappa." And I said "Okay, who's Frank Zappa?" And he said, "You don't know who Frank Zappa is?" and I went " Well, no. Is he a musician?" "Yes." "Well, what does he play?" "He plays guitar" " Does he record? I've never heard of him. He doesn't play jazz because I would have heard of him. And he doesn't play top 40 because I'm knowledgeable about who plays top 40. So what kind of music does he play? Where is he?" And he pointed to him; he was in the back there. And my vision was much better then, and I said, "He looks like a guy I saw on a poster—a music store in Haight Ashbury—sitting on a toilet flipping the bird. Is that him?" He says, "Well, yeah." I said, "Well what does he want with me?" "Well, he wants to talk to you." And I thought 'Okay, but that's not a very good endorsement—some weird guy sitting on the toilet—wonder what he wants with me?' [...] I wasn't familiar with his work; I'd never even heard his name before. I was just a top 40 musician. So I went back and was introduced to him. [...] He said, "I like the way you sing, and I like the way you play. I'd like you to come to Europe with me next week and do a European tour." I said, "I've got to be honest with you; as I told your road manager, I'm not familiar with your music." He said, "Well, that doesn't matter—I'll come over and teach you everything you need to know on Monday." "Well . . . err. Okay, who's in your band?" And he said "George Duke, Jean Luc Ponty . . . " I said "Stop right there . . . [...] I have all of George Duke's stuff—with Cannonball Adderley. I have a couple of Jean Luc Ponty albums. There's nothing you can teach me in one day that's going to prepare me to play a tour or concert or engagement with George Duke and Jean Luc Ponty; it's not possible. And there's no way in the world that I would accept such an offer knowing the calibre of musician that they are. But if they play with you, you must be good. Because they're really good." And he says "Don't worry, we can do it." And I said, "It's not possible. Number one, I have a contract: I'm booked to be here for three months and we've only been here six weeks; we have another 6 weeks to play." "Well, I'll buy the contract." "That's not the point—you can't buy this contract because it's not a written contract: it's a verbal one between two gentleman, the club owner and myself." [...] He says, "I wish you'd reconsider." "Well, I can't because I promised these guys. And this is paradise; why would I want to leave here to go and embarrass myself in front of two of my idols? That wouldn't be very smart. No, I'm sorry—I'm going to have to decline your offer. I appreciate it and, because of the personnel in your band, I feel quite honoured for you to even suggest such a thing. But this is my number, and I'm not doing anything after October."

October-December, 1973—US & Canada

Jean-Luc Ponty

In the case of Jean it was very simple. He tried a maneuver which I

thought was in extreme bad taste. He tries to stick me up for a large amount of

money. It was one of those things that if you don't pay me this gross amount of

money I'm going to leave and I said goodbye. And then he found out that he was

unemployed . . . I don't take very kindly to that kind of stuff 'cause I treat my

musicians fairly and when they try and do things like that to me I get pissed

off.

Ian Underwood

In the case of Ian, at the time we were gonna do this one tour, he couldn't

make the tour because he has a daughter by a former marriage and he had to stay

home and take care of her 'cause the mother was doing something and blah blah

and so he was stuck.

Napoleon Murphy Brock

As for Napoleon, Zappa had met him in Hawaii. He recalled: "He was working in a club called The New Red Noodle. I went in there one night while I was on vacation and just happened to see him and I thought he was a really good performer and I asked him to join the group. He said he'd like to but he couldn't as he still had a seven-week contract at the bar. And so I said 'well, here's an honest musician', and after his contract ran out at the bar he came over and rehearsed with us and he's been in the band ever since. It's been about a year."

Next thing I know, in October, I get a phone call. He says, "Hi, this is Frank Zappa." I said "Oh, hi. How're you doing? I remember you." He says, "Well, I'm at the airport." And I said, "I don't really know what that means." He said " Well, I just got back from Europe. I just got off the plane. I'm at the airport. You told me to call you, and I'm calling you." And I said, "Well, yeah. But I didn't mean for you to call me at the airport—you could have waited until you got home." He said, "No, it's important. I want you to come down as soon as you can. Can you come down and make a rehearsal next week?" I said, "Sure, I'm not busy right now—I have no more engagements" So I went down to the audition. He introduced me to everyone: Ruth, Tom Fowler and Bruce Fowler, Jean Luc, George and Ralph Humphrey. He says, "Well, sit down and take a listen." And they played about ten songs without stopping. Seven or ten—I forget how many because I couldn't separate them. I didn't know where one stopped and the next one started because of all the diverse time signatures that he uses in his music. But I knew there were at least seven different songs. The next thing I knew, they'd finished and he came down and says, "What do you think?" And I'm like "Whoa! How did you do that?" It's quite interesting, you know. Well, he asked me "Do you think you can do it?" I said, "Sure." Because to me it was the same as a rock opera—it had all the characteristics of a Broadway musical, except it was a little weird. A lot of different time signatures and everything. That was the jazz element—you know, with all the jazz musicians, I could understand that. And I understood that all of the musicians were from the music conservatory, so that made sense too. And I figured I could do this. I said, "This is a real good opportunity for me." And he says "Sure, let's do it." Next thing I know, "Here . . . " I get a big stack of charts " . . . this is what you'll be singing"!

[...] It was a very difficult time for me because . . . it would have been a lot easier if I had heard his music before, but it was very foreign to me. [...] And Chester Thompson came in the next day, so him and I were basically on the same page as far as playing Frank's music. He had never played it before either. He would play with people like Webster Lewis, who were just basically jazz. But he had also graduated from the Berklee School of Music, so he was quite a good drummer. But him and I, we were just being introduced to the band at that time so we were collaborating, and we were going "Shit! Did you listen to that? Did you look at those charts? This is ridiculous!" That was the hardest part. And the most memorable, because when we started the tour, all of the members of the band would request that I be put in a room at the end of the hall—as far away from them as possible.

IB: Why was that?

NMB: Because I'm up all night practising! He wouldn't let me play my saxophone and flute on stage until I memorised the parts. I said, "Well, why even bring them?" He says, "No, no, no, no, no. You need to learn it. And as you learn them, then you can play them." So I had my saxophone and flute on stage for the first couple of concerts that I didn't even play at all. I just set them up. Frank said, "Set 'em up so that people get used to seeing them."

It was the end of September. They weren't there (Europe) as long as they thought they were going to be. They were only there for about five weeks. I went down there in September; we started with rehearsals in September and October. Chester Thompson came in the day after I got there, and we were touring by the end of the year. In November we were on tour. Two drummers—Chester Thompson and Ralph Humphrey were playing drums in the band; and Ruth Underwood. Jean-Luc had gotten a recording contract about then, and a deal with a record company, so he quit then. Ralph Humphrey was there, Ruth Underwood was there, Tom Fowler, Bruce Fowler, George Duke, Frank, and myself. It was great.

Chester Thompson

The tour manager at the time was also from Baltimore, my hometown, and Frank was from Baltimore as well. I had known the tour manager before he ended up working with Frank, and Frank was looking for a second drummer because Ralph Humphrey was already playing in the band (as a drummer), and he wanted to specifically try a two drummer thing. So, I got an audition and he liked the way I played, and that was that.

Jawaka, alt.fan.frank-zappa, March 26, 2010

Re: Chester Thompson to be awarded Curtain Call Award at Belmont School of Music

Afterwards a Q&A. Lots of FZ's.

How did he end up working for Zappa? His told of training to be a school bus driver in Baltimore, as many musicians there did that so they could have more free time to play. He likes to drive, anyway. He and FZ had a production/road manager in common. On the weekend before he was to start driving Monday morning he gets a call to audition for Frank, cross country. No cell phones or answering machines in those days. Still does not know how those kids got to school on Monday.