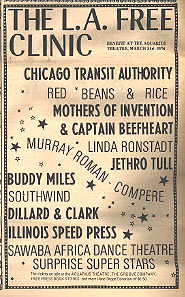

Bizarre/Reprise

Reprise Records has obtained exclusive worldwide distribution to all product from Bizarre, Inc., recently formed by Frank Zappa and Herb Cohen. [...]

Reprise general manager Mo Ostin termed the agreement a milestone in the history of Reprise. [...] By terms of the agreement with Reprise, Bizarre will maintain complete artistic control over material, art work, and advertising, with Zappa in charge of all record production.

First release under the deal is slated next week, when a double-record album containing the last recorded performance of Lenny Bruce will be issued. Entitled "Berkeley Concert," it is the only complete recording of a Bruce concert available on disk.

The first Mothers Of Invention album is set for February.

Under the umbrella of Bizarre, Inc., general manager Herb Cohen will also serve as head of the management division. The parent company will hold personal management contracts with many of the artists signed to Bizarre.

Other members of the Bizarre staff include Neil Reshen, business manager; Joe Gannon, formerly with A&M Records, general manager of Bizarre Records, who will also work in the areas of management, concert promotion and television and motion picture production; Grant Gibbs, director of marketing; and Cal Schenkel, art director. Reshen is heading up the New York office at present.

Bizarre is maintaining a suite of offices at 5455 Wilshire Blvd. in Los Angeles and 150 West 55th St. in New York.

Zappa is curiously enough, for such an anti-establishment figure, an extremely acute business man. And one of the "cutest" features of the deal he negotiated with Warner Records is that at the end of their five-year contract the group get their masters back.

" . . . That's what I call a good deal," says Frank. "You make a record, and what normally happens is that the record company owns the tapes for ever—it's not your music anymore. I happen to like the idea of retaining my so called works of art."

Erik Gerritsen, "Frank Zappa," Hot Licks, December, 1975

In 1968, disenchanted with his record company (MGM-Verve, with whom he is still battling out a royalties lawsuit), the Mothers switched to Warner-Reprise, who distributed Zappa's own labels, Straight and Bizarre.

January 24-25, 1969—Shrine Exposition Hall, Los Angeles, CA

Art Tripp, to Charles Ulrich, May, 2014

We played the Shrine several times in that era. That particular gig may have been the time where Frank had half-heartedly orchestrated a sado-masochistic drama on stage during which he almost got whipped. Kim Fowley was involved, and a couple of them went overboard. The Gnarler (Dick Barber) had to come out and break it up to protect Frank. We just kept playing . . .

I remember those shows pretty well, since—despite the Fowley stunt—they were lots of fun. That's where I met Crazy Jerry—a speed freak who loved vibrations and electricity. He'd come up to me raving about the show. I asked him from where he watched it. He said that he'd spent much of the show underneath the stage on his back with his feet pressed up against the bottom of the stage floor. He did that so he could feel the vibrations. The guy was actually brilliant; and once you got past his veneer, he was a fascinating guy. After we realized he was harmless, he even stayed over once or twice at my place in Laurel Canyon. He had a legitimate prescription for injectable speed, which he carried in his boot along with his needle apparatus. He'd broken his ribs a couple of times in the process of bending steel re-bar across his chest.

According to Lowell [George], Frank Zappa's trip was shocking people, pushing them to their limits of tolerance. Lowell cited an example: the band was working a concert at the Shrine Auditorium in Santa Monica, scene of many former freak-outs. The first set went well, then the kids rushed the stage, and the band members became a little worried. In the second show Frank had a chick named Della come on stage. He asked for a volunteer from the audience to whip her. No one volunteered. Then Kim Fowley, an archetypal L. A. weirdo who requires a whole book to himself, offered his services, but he was refused. Finally an old road manager of the Mothers agreed to come on stage and beat the girl with his belt. Both the chick and the road manager got carried away, and soon he was flailing out at the rest of the band members who by now were bunched together behind their instruments. Kim Fowley got into the scene and was also whipped. By 2:00 A.M. the vice cops were in the wings waiting for someone to take off his clothes. The audience was enthralled. "You could just see rows of eyes and open mouths," recalled Lowell. Then on went the lights. End.

"There's a girl in Los Angeles named Della who likes to get whipped. She came to the Whiskey with a child, handed the child to somebody and said. 'Would you mind whipping me in the middle of the show?' and I said. 'Sure, if that's your idea of a good time.' When she came on she had on a little skirt, had some tights on, had this big belt and she wanted me to beat her while the band was playing. I MEAN beat her, BEAT HER, to hurt. HURT HER! And I [said] 'sure,' you know. 'anything to please.'

Finally she wanted me to hit her with the buckle. She was a nice person, she just wanted to get beat, so I took the buckle and went BOW, like that," as he demonstrates, "and she went flying across the stage, just rolled up into a ball screaming. We're just playing music," he says, looking around matter-of-factly.

"So about two months after that," he continues, drawing from his cigarette, "we're playing at the Shrine Auditorium and Della shows up again, and wants to get whipped. I say 'Nah, nah, I don't want to beat her, let's get somebody from the audience.' So I say. 'Is there anybody in the audience who wants to whip Della?' So Kim Fowley says. 'Hey I'm really far out, yeh, fantastic. I'll do it.'

He jumps up there and starts to beat her a little bit, but he's making a big dramatic production out of it and the girl just wants to get beat, you know, and he wants to be a star while he's beating her, and she's going. 'No way!'

Then this guy who's named Skippy Diamond, who's now a chiropractor in Los Angeles. Skippy's this guy with a head built like a barrel, about 5'7". Kim Fowley's 6-something, real skinny. Skippy walks up there, takes the belt away. Skippy's normally a mild mannered guy, takes the belt away from Fowley, doesn't beat Della, starts beating FOWLEY." Zappa says with wide eyes!

"And seriously. Fowley is on the floor with a microphone screaming for help at the audience and Skippy's beating HIM, then beating Della, wailing around the stage with this belt, you know . . . I'm just playing," Zappa finishes in laughter.

We played a show at the Shrine again [January 24-25, 1969]. Fleetwood Mac were on second [...]

That's also the gig where Frank had worked out a little skit for the stage which he was famous for. It was arranged for this girl named Gigi to come onto the stage. She was one of the chicks who hung out with The GTO's and she liked to be whipped with a belt. She was going to come on when we did 'Pachuco Hop' and get a little mocked whipping.

There was this guy called Skippy Diamond who was a friend of ours. The "Gentle Bear" was what we called him and he was a pretty-good-sized guy who used to be a wrestler. He had heard about what was going to happen, so he was standing over by Gigi. When it was time for this to all happen, he grabbed the belt and ran on to the stage and started wailing into the girl and the audience was going wild.

Kim Fowley, who just loved the limelight, was right in the front row and of course, he thought, "Hey, this is too good of an opportunity for me to pass up!" so he jumped up on the stage. As soon as Skippy saw him, he started wailing on him too because Skippy never really liked the guy!

The next person he started on was Frank and he managed to whack him a few times. I mean he was wailing on everybody you know, kind of temporarily insane. Frank was trying to get away from Skippy but there he is in front of five thousand people.

Skippy said, "Come on Frank, you started this so take your fucking medicine!" Now that's the second time when one of those little things that Frank liked to do backfired. I was glad that I was behind the drums and so was Artie.

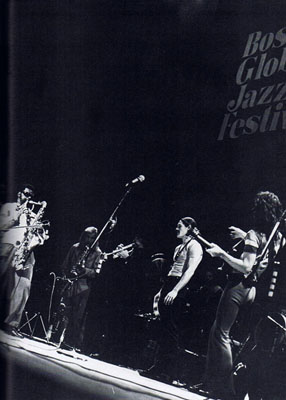

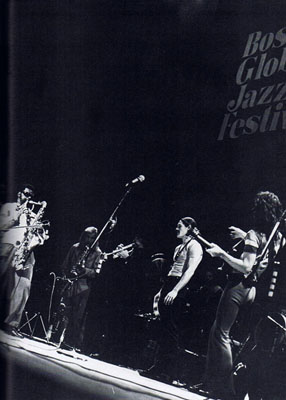

January 31, 1969—Boston Globe Jazz Festival

Downbeat, May 1, 1969

[The Mothers Of Invention] started very free—electronic shrieks and whines, scale-running from hornmen Ian Underwood, Bunk Gardner and Jim Sherwood, and some falsetto sing-song by electric bassist Roy Estrada. They settled into a jazz framework with a riff similar to the Jazz Crusaders' Young Rabbits. Short solos by Don Preston on electric piano and Gardner on trumpet (using the false low range, like Rex Stewart on Lion of Judah) . . . and then pandemonium broke loose as Kirk wandered out and jammed with them for the rest of the night. All stops were out; [Rahsan Roland] Kirk wailed, the Mothers dug it and responded with uncanny support. Free stuff, Kirk weaving in and out of the flow of sound patterns into which Frank Zappa directed his crew. Basie riffs by the reeds, a raunchy stripper blues with Kirk sounding as raspy and earthy as he ever has. Zappa instantly picking up Kirk's concepts and playing telepathic guitar counterpoint. Choreography: high-kicking, everybody on his knees, everybody on his back. Tune ends, crowd goes bananas, "More! More!" Okay: All Night Long. More of the same, only different. After this one, and a short sardonic rendition of Louie Louie (with the lyrics of Plastic People), the audience was close to berserk. Wein had to close the curtains, turn up the house lights and beg them to leave, which they ultimately, happy-sadly did.

That particular set is lost forever, but Kirk and Zappa are crazy if they don't make a record together. The Mothers are capable of many other things—so is Kirk—but this was too much, and nobody with half an ear who heard it could ever again say that jazz and rock can't combine without damagine one of the idioms. An incredible, exhilarating, exhausting, exciting set.

I read in Down Beat that you did a 45 minute set with Roland Kirk at a Boston Jazz Festival. Were you billed together, or did you just play together because Kirk was there?

We were on the same show and I met him after he had done his part and said "Would you be interested in playing with us?" And he said he didn't know. And I said "Well, you've never heard the group before—you don't know what we do. If you like it—come on out on stage and start playing, and we'll back you up". So we'd played for about five or ten minutes and he came wheeling out there with horns hanging all over him and blow his brains out.

It was completely free—nothing planned.

No, he just came bopping out there and we did it.

Got any plans to record together?

Well, he asked us to you know, but we haven't gone ahead with any special schemes yet.

FZ, quoted by Suzy Caowan, New Music Magazine, April, 1976 [English translation by Tan Mitsugu]

I met [Roland Kirk] at the backstage of Boston Jazz Festival, and asked him to play together if he was interested in our music. Then, during our set, led by his attendant, he came up to the stage. As you know, he's blind. But his body understood all of our signals. At one point, everybody in the band was supposed to get down on their back and kick their feet in the air while they still keep playing. As soon as we got on our back, he also got his back. When we got up, he also got up. He grasped everything. He is an excellent musician. Three weeks later, we played together again in Florida Jazz Festival.

The first time we played with Rahsaan Roland Kirk was at the 1968 Boston Globe Jazz Festival. After his performance, when introduced to him backstage, I said I really liked what he was doing, and said that if he felt like joining us onstage during our set, he was more than welcome. In spite of his blindness, I believed we could accommodate whatever he wanted to do.

We began our set, wending our atonal way toward a medley of 1950s-style honking saxophone numbers. During this fairly complicated, choreographed routine, Rahsaan, assisted by his helper (can't remember his name), decided to join in.

We played at the Boston Globe Jazz Festival with Dave Brubeck and Roland Kirk the night of my thirty-first birthday on February 1st.

Roland sat in with us for a jam and we played a song called "Behind The Sun" where Roland, Bunk, Ian, and Motorhead were all on their backs honking away just like the old days.

January-March, 1969—East Coast Tour

February 7-9, 1969—Thee Image, Miami Beach, FL

February 14, 1969—Columbia University, NYC, NY

February 16, 1969—The Ballroom, Stratford, CT

February 21, 1969—lecture at New School, NYC

Zappa was guest lecturer on Friday at 6 p.m., just before the Fillmore concert, at a joint meeting of my History of Popular Music class and Charles Hobson's Afro-American Music class at the New School. The public was invited, as they will be for four other concerts and lectures this semester, and after a few polite moments, they started getting into him with questions about his relationship to the public, the revolutions, and why all the funny stuff. Did he ever think about the possibility of becoming another Mozart? Does he like the Beatles' music? The answers can be heard on a WBAI re-broadcast in a couple of weeks, but I'll reveal that, according to Zappa, he puts all that different kind of stuff in his music because it gives him a kick to hear it and because he likes to laugh. At any rate it was a wild set, and it ended with an audience member's sudden comment, "But you're so human! I thought . . . "

February 21, 1969—Fillmore East, NYC

If you're one of the people who groove to all music in a fairly intelligent-but-visceral manner the Mothers were storming your soul last weekend. They are probably the best equipped musicians in rock and roll. They can not only play r&b, new classical jazz, and sigh-ka-delic to perfection, but they also create in them. The speed tonguing of the horns in "Uncle Meat" was breathtaking. As usual, Don Preston, the number one keyboard man on the pop scene was raging in his solo on electric piano. The piece grew and swept all before, except of course the Mothers' r&b fan faction. All of the funny stuff—Motorhead and Roy Estrada screeching, singing opera, and felltiotizing an alto sax—was on the beat, in the right un-key, and at the psychologically right time in the piece.

February 22, 1969—Fillmore East, NYC

That was a great night. In fact, the two nights we played there, all four shows had stuff in it that looked so outrageous. And I came up with maybe two albums out of those two nights. Just crazy. I wonder where that chick is? . . . One night we improvised an opera . . . [...] Her name was Shirley Ann. She used to sing in Sweden. I don't know whether she made records . . . [...] She was standing backstage talking with Jimmy Carl Black who tried to get in her pants one time when we were in Sweden and she wasn't going for it, you know, so he was hustling her and when he wasn't meeting with too much success back there he decided he would finally introduce her to the rest of the members of the group. So he said, "This is Shirley Ann, and she sings." So I said, "Sing." So she sang a couple of bars and I said, "Would you go on stage with us?" We had to really con her into coming out there. She said, "What'll I sing?" I said, "Whatever you want." So she started off singing, "I am made of fire and air, come and touch me . . . " [...] She was making up this weird stuff. So Lowell (George) started singing duets, with her, Motorhead was snorking . . .

February 23, 1969—Rock-Pile, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Ritchie Yorke, "4,000 Jamming Rock Pile Enjoy Mothers Keeping It Clean," Globe Mail, February 24, 1969

The Mothers were straight, and it didn't seem to disappoint two capacity houses at the Rock Pile. Packed in like a bunch of grapes, more than 4,000 people—some of whom had lined up for over an hour—watched as the Mothers proved themselves to be excellent musicians.

[...] During a 40-minute song, facetitiously titled "String Quartet," [FZ] acted out the traditional conductor role, singling out members for solos, ceremoniously, waving the group into tempo changes.

But the most amusing part of the Mothers' performance was the group doing its parodies (or were they sendups?) of mid-fifties rock 'n' roll—the era when groups woo-woo-waahed their way through almost everything.

The Mothers offered several selections in this vein, including "Lonely Nights" and "White Port and Lemon Juice," adding to the vocal parodies with some hilarious choreographed stage movements.

In Toronto in March, the Mothers of Invention played two concerts at the Rock Pile. The first was innocuous, but at the second show a former member of the group simulated sexual intercourse with a girl who turned out to be his wife, then for a finale turned his back and dropped his trousers. Rock Pile manager Rick Taylor, 24, didn't like it, but he didn't try to stop it. "Are you crazy, man? Just picture me trying to stop it in front of 2,000 fans.

"I do think it was kind of an insult to members of the audience who'd paid $3 each to see a musical group. They didn't pay to see someone's backside." Taylor says, however, that he would take action if a group member attempted to masturbate on his stage. "I'd ask my stagehands to stop him, and if they refused, I'd keep on moving up the staff ladder—firing people. By that time I figure the artist would probably have finished anyway, and I wouldn't have to stop him."

One girl who was at the Mother's concert disagreed. "I mean, tough luck. Who cares if a guy takes his trousers off? Plenty of worse things can happen. Big deal." (She didn't want her name to be mentioned in case her mother should see it.) Frank Zappa of the Mothers of Invention is equally unconcerned. "The incident was simply something unpremeditated, unexpected even by the Mothers.

The guy wasn't even a member of the present group. And he just came on up and did it. What could we do?"

I worked for Frank in Toronto, Canada where I did an opera with Roy Estrada (bass player for the Mothers of Invention), at the end of the gig I give the audience my butt, I pulled my pants down and gave them a B.A. It was a fine rendition, the place was shredded, the audience was clapping for 10, 15 minutes. We even had to come back and give an encore. I remember there was an encore.

Another [memorable moment] was the night I introduced Frank Zappa at the Rockpile Club—Toronto's version of the Fillmore. In the course of his set, during an extended improv break, Frank came back out on stage and peed all over the front row of the audience—literally pulled his dick out and pissed on them! No one complained. They all wore it in the literal sense of the word.

February 28, 1969—The Factory, The Bronx, NYC, NY

March 2, 1969—Philadelphia Arena, Pennsylvania

April 25-May 4, 1969—East Coast

April 26, 1969—Memorial Hall, Muhlenberg College, Allentown, PA

We did play a gig with The Turtles one time in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

May 2, 1969—Clark Gymnasium, SUNY, Buffalo, NY—Simon & Garfunkel

FZ, interviewed by Lon Goddard, Record Mirror, June 7, 1969, p. 12

Paul Simon? I'll tell you something about Paul—I was in a record store buying some strings, when in walked Paul Simon with a glazed expression on his face. He came up to me and said, "I think I have to talk to you about something. Why don't you come up to my place for dinner." Later, I took one or two friends around to the address he had given me and there he was, sitting with his girl friend, listening to a Django Reinhardt album. We sat around and talked for a while and I found him to be one of the most unhappy people I'd ever me.

You know why? He had to pay thousands in income tax last year because he's so rich, he's rich, but he's not happy. He was very bored. I said, "Why don't you come on the road with our band?" He thought this was a great idea and he pulled out this scrapbook of old pictures from the days when he and Garfunkel were billed as Tom and Jerry.

Remember? They had a number one hit with a song called "Hey, Little School Girl." I asked if he'd like to come up and do a concert in Buffalo (upstate New York) the next night. He was really hot on the idea and immediately phoned Art Garfunkel. He dug the idea too, so we decided it was on and I billed them as Tom and Jerry, putting them on first. Of course, when they appeared, everybody knew it was Simon and Garfunkel, but they went on to do only Everly Brothers numbers and "Hey Little School Girl," etc.

The public wanted them to play their hits. They wanted to hear "Sounds Of Silence." We went on and did our stuff and called them back for a combination finish and Simon said, "We will now do the teeny-bop version of 'Sounds Of Silence.'" He took an old rock melody and sung to it, repeating "Sounds of Silence, Sounds of Silence, Sounds of Silence," over and over again for going on ten minutes. They loved it. All they wanted was the words. The public can be really fickle.

I was in Manny's Musical Instruments in New York sometime in 1967, and it was raining outside. A little guy came walking in, kind of wet, and introduced himself as Paul Simon. He said he wanted me to come to dinner at his house that night, and gave me the address. I said okay and went there. [...] Then Art Garfunkel came in, and we talked and talked.

They hadn't been on the road in a long time, and were reminiscing about the 'good old days.' I didn't realize that they used to be called Tom & Jerry, and that they once had a hit song called "Hey, Schoolgirl in the Second Row."

I said, "Well, I can understand your desire to experience the joys of touring once again, and so I'll make you this offer . . . we're playing in Buffalo tomorrow night. Why don't you guys come up there and open for us as Tom & Jerry? I won't tell anybody. Just get your stuff and go out there and sing 'Hey, Schoolgirl in the Second Row'—just play only your old stuff, no Simon & Garfunkel tunes." They loved the idea and said they would do it.

They did the opener as Tom & Jerry; we played our show, and at the encore I told the audience, "I'd like to bring back our friends to do another number." They came out and played "Sounds of Silence." At that point it dawned on everybody that this was the one, and only, the magnificent SIMON & GARFUNKEL.

It was 1968 and I was shopping at Manny's Music Store in New York City and Paul Simon, who I didn't know—I didn't even know what he looked like—came in out of the rain, got talking and invited me out to his house for dinner. I said OK, went along, was introduced to Garfunkel, and they started pulling out their photo album of when they were Tom & Jerry in the late '50s. They made some comment about how they missed being on the road, so I invited them to come on the road with The Mothers Of Invention and open for us in Buffalo the next night—as Tom & Jerry. They went out on stage and sang this earlier repertoire and the audience had no idea who it was. After we played our show, I brought them back out on stage to do some of their contemporary hits—at which point the audience realised that they'd been had.

I also remember the band going on the road to Buffalo, NY for a weekend, and Simon and Garfunkel came along for some fun! We did a lot of bizarre stuff in the hotel and in our rooms that Simon and Garfunkel filmed. Later on at the concerts, we would introduce them as mystery guests, and while they sang, we did our usual weirdness right along with their singing. It sticks out in my mind because I remember it was my birthday, and after going to a party following the concert, I was driven back to the hotel by a gorgeous Virgo school teacher who decided to come in and help me celebrate by sharing a fine bottle of wine!

Joseph Fernbacher, "Mothers Of Invention," The Spectrum, May 7, 1969, p. 8

A weating body of students sat through the first lecture of a new science course Friday night in Clark Gym. The visiting professor was Frank Zappa—accompanied by his nine mothers. [...]

Kicking off the evening were a pair of aspiring young singers called "Tom and Jerry." [...]

Actually this group was none other than those fantastic leaders of the folk world, Simon and Garfunkel. They just happened to be in the area at the time and decided to visit Dada Frank and Company. To say that one's mind almost stammers at the sight of lanky Art Garfunkel and pudgy Paul Simon weaving their way between Frank Zappa and his music is an obvious understatement. After doing a set Simon and Garfunkel gracefully left the stage to the Mothers of Invention.

The Mothers began with a heavy piece taken from their latest lp entitled "Uncle Meat"—so is their new lp. [...]

After picking myself off the floor, the Mothers brought back Tom and Jerry, who did some more Everly Brothers' tunes and wandered about the stage looking lost. They did do a stirring rendition of "Sounds of Silence," circa 1950, complete with shu-bops and dong-dongs, and "Oh. baby lets do it once in silence. "

Obviously tired and sweaty, the Mothers wanted to split. The audience didn't like this. So Zappa put us into a bind. If we clapped and jumped up and down, we made asses out of ourselves and if we didn't do anything, they would leave. So we made asses out of ourselves. Zappa came back, but was obviously angered.

May 17-24, 1969—East Coast

May 19, 1969—Massey Hall, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Jack Batten, "Boss Brass Is Merely Brilliant; Zappa's A Wizard," Toronto Star, May 20, 1969

Zappa brought nine musicians to town this time, a smaller group than he offered for his concert last winter at the Rock Pile, and they played five numbers. Two of them were funny but dispensable parodies of 1950s rock 'n' roll, while the other three were long, exhilarating and complex compositions that ransacked through John Cage, free jazz, the Theatre of the Absurd, hard rock and Zappa's own special genius.

The three long pieces—"A Pound for a Brown-Out on a Bus," "Eye of Agamoto" and "The Return of the Hunch-back Duck," if you care about titles—suggested that Zappa works in the style of Duke Ellington.

[...] "Eye of Agamoto" [...] was launched with a freelance, instantly improvised ballet that employed four dancers (all of them band members), some plastic masks, a couple of brassieres and two rubber ducks.

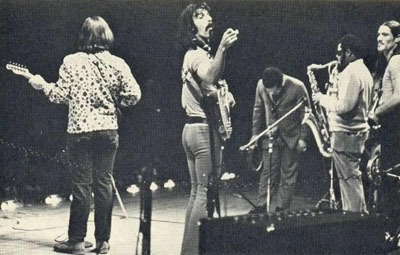

May 24, 1969—Rock Pile, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

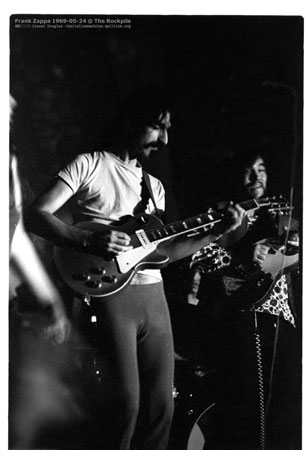

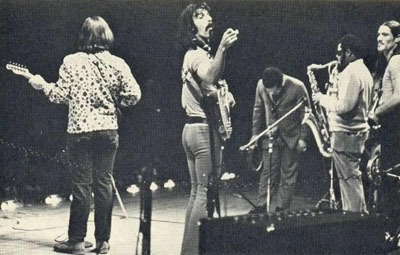

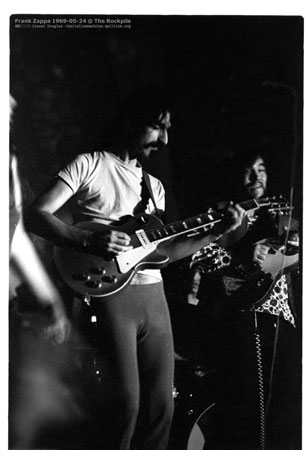

[FZ, Lowell George. Photograph by Lionel Douglas.]

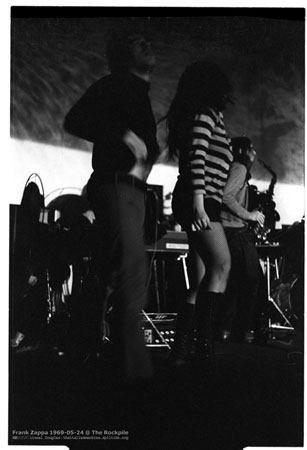

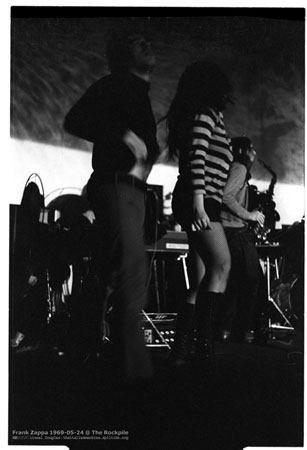

[Carl Franzoni, unidentified girl, Ian Underwood. Photograph by Lionel Douglas.]

Denis Griffin has discovered that the guest vocalist's name is André Beauregard.

Yves Leclerc, "Mais qu'est-ce que les Mothers ont encore invente?," La Presse, Montreal, August 21, 1969

Près de lui, il y a un garçon au veston rouge phosphorescent qui tantôt, à la fin du "show", est monté sur scéne et s'est mis à chanter en français. il s'appelle André Beauregard, il est copain avec les Mothers, et c'est la troisième fois qu'il chante sur un de leurs spectacle.

Au debut, c'est surprenant, ensuite c'est assez bon et après trois ou quatre minutes ça devient trop long. Beauregard n'a pas vingt ans, il a rencontré les Mothers à New York il y quelques mois: "Il voulait chanter, personne ne l'écoutait. Il se tenait avec nous, alors nous lut avons dit: "Vas-y", et nous l'avons fait chanter, deux fois à Toronto, et aujourd'hui à Montréal" explique Zappa, le plus simplement du monde. Continuera-t-il? Personne ne le sait.

Google Translate:

Near him, there is a boy in a phosphorescent red jacket who, at the end of the "show," went on stage and began to sing in French. his name is André Beauregard, he is a friend of the Mothers, and this is the third time he has sung on one of their shows.

At the beginning, it's surprising, then it's pretty good and after three or four minutes it becomes too long. Beauregard is not twenty, he met the Mothers in New York a few months ago: "He wanted to sing, no one was listening, he was standing with us, so we said, 'Go ahead,' and we made it sing, twice in Toronto, and today in Montreal," says Zappa, simply in the world. Continue there? Nobody knows it.

May, 1969—Lowell George

Russ Titelman was starting a publishing company and he asked me if I wanted to co-publish the tune ["Willin'"] with him and see what he could do with it. So I recorded it and went on the road the same day with The Mothers and was gone for about five weeks I guess. Then I came back and nothing happened, but somehow a demo of the tape got out and it was the rage of the Troubadour.

Lowell George, ABC FM Australia, c. 1978

I never did [submit "Willin'" to FZ]. I was always smart enough to not submit it. But he did hear it once, and a few days later I was offered to start my own band. Which was a nice way of firing me, I think.

[...] Most of the [first Little Feat] album was demos. "Willin'" was a demo I did when I was in the Mothers. Matter of fact I did it the morning before we left for Passaic, New Jersey, or someplace like that.

[Lowell George] stayed with us for about eight months, just up until the time that we went to Europe. In 1969 Frank gave him his walking papers so to speak, told him that he thought Lowell ought to start his own band—I told him at the time that if he did, he should call it 'Little Feet' because he had little bitty feet. And, as it turned out, that's pretty much what happened.

Lowell had a band in California called the Factory, guys that had opened for us on several occasions. Lowell was very young at the time. He stayed with us for about four months, just up until the time we went to Europe. Frank gave him his walking papers so to speak. He told him he thought Lowell ought to start his own band. I told him at the time that if he did, he should call it Little Feet because he had little bitty feet. And as it turned out, that's pretty much what happened.

I actually got to know Lowell [George] way before he joined the Mothers. He had a band called The Factory and I used to go up to their house on Lookout Mountain Road in Hollywood and trip out on LSD. We were already trippin' pals before he joined the Mothers and in fact, he used to room with Roy Estrada and myself. In the One Fifth Avenue hotel in New York in early 1969 we were rooming together when he wrote most of "I'm Willin." It has always been one of my favorite songs of his. I have even recorded it a couple of times.

Lowell [George] was a great friend of mine and one of the most talented people to ever grace the music industry. We became friends when Lowell joined the band. I was responsible for forming Little Feat. I introduced him to all the guys but because of my strong relationship at that time with Warner Brothers Records, I arranged his first record deal with the label. History was made.

The next thing we hear is that Lowell won't be coming to England with us! Frank had cut him loose. Frank told him it was time he started his own band and it broke Lowell's heart because he wanted to go to England so bad. Man! It just devastated him! We were never given a proper explanation for it because he wasn't fired—he was just cut loose! Frank had never kept a second guitarist in the band for any length of time. I believe that Frank really didn't want another guitar player in the band. He was also doing most of the vocals by then. Lowell was cool about the whole thing and he did what he was told—like everybody did in the Mothers!

The drug references, first and foremost, I think that put Frank off. But Frank dug Lowell. I mean, he liked him, so he knew "Willin'" was a good song, and that Lowell really ought to be putting his talents elsewhere, and if Frank could help on that, then that's what would take place. I wasn't exactly sure in the beginning how much or what Frank was doing behind the scenes to help us, because . . . well, we took a year before we wound up at Warner Brothers, for example.

Lowell George was not exactly fired but rather let go and it is true that FZ advised that with his talent as a performer, musician and songwriter he should put his own band together—And it is true that he did assist in many ways. [...] Lyrics were never an issue and in fact FZ frequently supported at his own expense everyone's right to freedom of speech and every artist's right to artistic expression.

Bill Payne, Jeff Simmons & Lowell George

In late spring of 1969 I took a drive from Isla Vista, a community hosting students going to UCSB just north of Santa Barbara, to Los Angeles that was to change my life forever. [...]

A few weeks prior, using a phony credit card, I had placed a call to Bizarre Records, Frank Zappa's label, in Burbank. I told her I played piano and organ and that music was my life. I wanted to join Frank's band, the Mothers Of Invention. Frank and the boys were heading to Europe, however, she said, and it would not be possible to meet with him at that time. She must not only have heard the anxiousness in my voice, but somehow accepted the fact I had the talent to be given a chance. She gently steered me in the direction of the band Eureka, on Frank's other label, Straight Records. A few days later, I met with Eureka's leader Jeffrey Simmons at the Tropicana, a seedy rock and roll hotel, on Santa Monica Blvd. The meeting was unsuccessful—in addition to playing guitar, Jeffrey also played keyboards and was not looking for any outside competition. Returning to Isla Vista, I placed yet another call to my contact at Bizarre Records telling her of the outcome with Jeffrey.

She asked me if I had heard of Lowell George.

I hadn't.

Lowell, she said, had played guitar and sang with the Mothers on two albums, Uncle Meat and Weasels Ripped My Flesh (which also happens to be the first Neon Park cover I had the pleasure of seeing), and that Frank had asked him to form his own band. I was given Lowell's number and gave him a call. I would make the drive to Los Angeles in a few days to meet with him.

[...] I felt I shared a kindred spirit with Lowell. His low key charisma made me feel even more welcomed and at ease than I already was. We talked for hours that night about every subject under the sun. A spinet piano (his mom's) was against the wall, and we traded musical quotes at each other, he on acoustic guitar, myself on the piano. What struck me most was his humor, his intelligence, and his innate ability to draw connections between disparate topics, musically, or otherwise.

I left the next day with an invitation from Lowell to come back the following week. Frank and the Mothers would be back from Europe in a couple of weeks and he would make the introductions. In the meantime, we could continue getting to know each other and try writing some songs.

I took the most important drive of my life to Los Angeles in the summer of 1969. In fact, it was probably around May of that year. And, I was driving down to Lowell's house. [...]

I started listening to Uncle Meat. [...] I said, "That's the kind of music I want to play." The problem was that Zappa lived in Los Angeles. And Los Angeles was one of the last places I said I would ever live. So, you know, once again, God's sense of humor was at work and I find myself getting a hold of Zappa's label and seeing if I could tag up with him. And he was gonna be in Europe.

But this guy named Jeff Simmons was available. And he was with a group called Eureka. And I'd seen Eureka, or heard them play, at a freak-out that Zappa and the Mothers did—my first, and I think, one of the few times I'd seen the Mothers play, at the Shrine Auditorium. So I'd heard Jeff's band play. So when they mentioned Jeffrey Simmons, I thought, "Well yeah, that's cool." So I went down and met him at the Tropicana Hotel in Hollywood down on Santa Monica Boulevard. I played him some piano and he said, "Man, I don't think this is gonna work. Because I play guitar but I play piano. You know what, you oughtta check this guy out named Lowell George. He's got a band going. Frank Zappa said to start his own band, and you might want to check him out."

So I went back up to Santa Barbara, back to sleeping on the beach, sleeping in my car, sleeping in friend's apartments. Once again put in a call to Bizarre Records. It took quite a few calls for them to accept that I was somebody that necessarily wasn't going to give up and I wasn't apparently too obnoxious. So one of the secretaries down there helped me and hooked me up with Lowell. We had a brief conversation, I went down to his house, and the rest is pretty much history. We hit it off in a big, big way.

I was just north of there, in Isla Vista, where the University of California, Santa Barbara was. I had a phony credit card that someone had given me. There were two labels that I could call: one was Bizarre, and the other was Straight Records. They were both Zappa labels. Naturally, I called Bizarre—though I'm sure the same person would've picked up the phone for both—and, you know, here I was on the street, basically, saying, "Uh, I play keyboards . . . " [Laughs.]

It took several calls to sort of get this person, this lady on the other end of the line, to take me seriously enough—or maybe she felt sorry for me—to put me in touch with Jeffrey Simmons, who was with a group called Eureka, which was one of the bands in Frank Zappa's stable. I finally did meet Jeff at the Tropicana Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard, and Jeff said, "Oh, well, I play keyboards, too, and this might kind of destroy what I'm doing, but there's this guy Lowell George that I really think you ought to try and reach." So Jeffrey put me on to Lowell.

May 30-June 7, 1969—European Tour

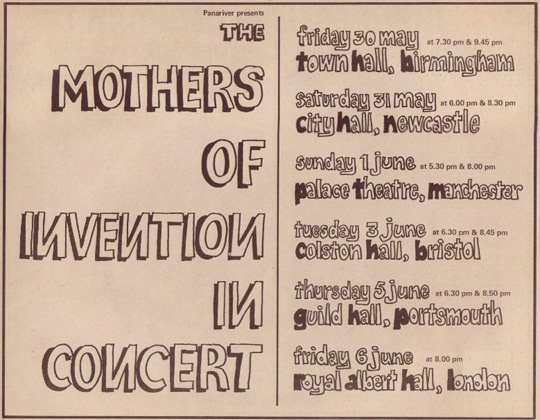

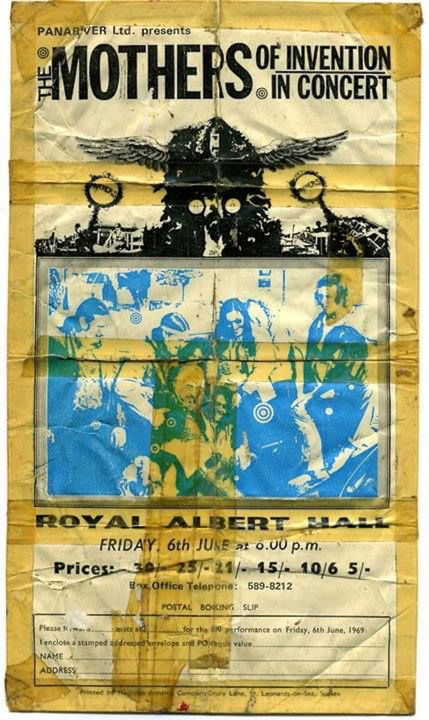

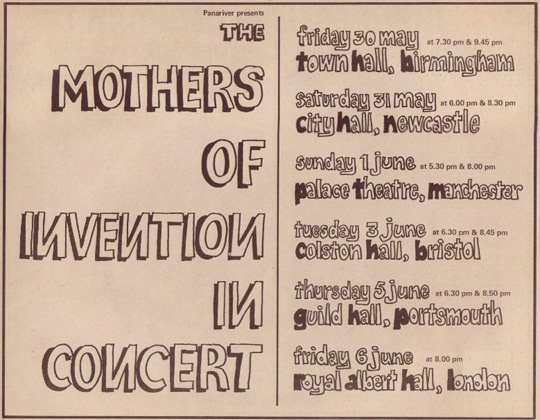

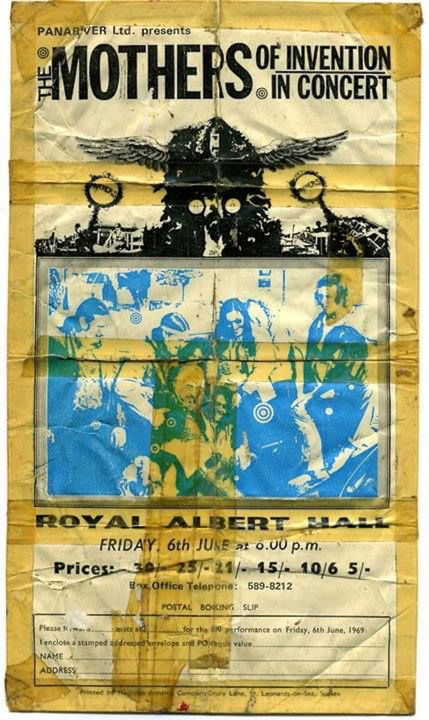

The Mothers Of Invention—the most controversial group in the world today—are to tour Britain from May 30.

This will be the first time that the group has been seen in Britain outside London. [...] The tour opens on May 30 at Birmingham Town Hall and continues at the City Hall, Newcastle (31), Palace Theatre, Manchester (June 1), Colston Hall, Bristol (3), Guildhall, Portsmouth (5), and London's Royal Albert Hall (6).

The Mothers will play the whole of each concert, with no supporting acts.

FZ, interviewed by Pete Drummond, Oz, July, 1969

How much of your music is notated?

50 per cent of it. The other 50 per cent is improvised and it's very carefully structured, and the live shows we do are all different, not just because of the improvisation but because of the way the building blocks of the show can be assembled.

IT #56, May 9-22, 1969, p. 19

May 30, 1969—Town Hall, Birmingham, UK

"Igor's Boogie," their complex opener, featured a tenor, trumpet, and two clarinet line-up which Frank later wrote out for me at our hotel.

"Hot Rats" which followed was a fine example of modern American orchestral music, which proved how advanced is Frank's writing and how skilled are the Mothers at interpreting his scores.

On the lengthy "Shortly," Frank played excellent guitar and after this hugely applauded marathon, which made great demands on the concentration powers of both audience and players, the light relief of a straight rock and roll set broke up the audience.

Jimmy Carl Black laid down THE most solid off-beat while the horn players dutifully swung their instruments in a beautiful parody of 1950 style rock. Biggest surprise was the appealing quality of Frank's teenage voice, well up to the standards set by such groups as Ruben & The Jets, on tunes like "Bacon Fat " and " My Guitar Wants to Kill You Mother."

The chamber music was Zappa's writing for unaccompanied trumpet, clarinet and bassoon and this proved as successful with the audience as anything else they cared to play.

June 1, 1969—Palace Theatre, Manchester, UK

The show in Manchester ws on a Sunday and there was a law in the theater that had been in place for a few hundred years. Bands were not allowed to sing any vocals on a Sunday and if you did you were subject to arrest.

So we had to play an instrumental show but that was not a problem for us since we weren't singing many songs anyway at that time.

June 3, 1969—L.S.E. Lecture

When the Lords of the spray-can came into collision with the Mother Of Invention in their slogan-daubed lecture hall on Tuesday of last week, there was an explosion of non-communication, an embarrassment spectacular, more aimless than the most inane TV panel show. [...]

The lecture began with Frank asking: "Any questions?" Friendly laughter—a settling down for the revelations and super-chat to come.

"How seriously do you take yourself and your music?" A question to set the ball rolling.

"Not enough to be dangerous." Ho-hos, then silence. Further questions, fail to spark much response.

Then the heavies got to work. One strident voice likened him to Bob Hope which earned a hearty round of applause.

They stamped on his "facetiousness" and clamoured for some positive statements on his beliefs. Sadly hit delivery of the concept of infiltration of media, government, church, army, etc. instead of direct confrontation, sounded weak and feeble. It merely induced groans and jeers.

"What are you doing?" demanded one youth, hotly. "I'm sitting here being abused." But there was to be no more laughter for Zappa wisecracks, and he lapsed into a kind of dazed silence.

"Are you upset Frank?" asked one kindly student summoning reserves of pity from his vastness.

"No, I'm not upset."

The students were upset, however, at statements like: "Everybody is part of an establishment. What makes you think you are not part of an establishment here? I'm in favour of being comfortable. People have different ideas on how to be comfortable. I just aim for that goal the same as anybody else."

"What happened at Berkeley last week?" "Oh, you want a hot poop—an inside on the demo? I'm not hot on demonstrations." "Yeah, demos aren't comfortable," called out one chap.

"People are really thrilled about rioting in the street. It's this year's flower power."

A cry of "ballocks" greeted this remark, and Frank was accused of being a narrow-minded, fantastically hostile, snappish bigot.

Zappa had failed to fill their need for a hero figure.

I asked Frank about the LSE lecture, and whether he had gone there with the intention of upsetting them.

"No—not at all. I was asked to talk to the students, so I went along. I don't like to talk, but I will answer questions, even their asshole questions. No, I didn't misjudge them—I had a pretty accurate idea of the mood of the students.

"It's difficult to sit in front of people who don't like a thing you say. It makes you a little bit nervous. It's disturbing to see people in colleges so impressed by such a lot of dogma.

"If you think I was too patronising in my answers to questions I would say the questions were idiotic.

"I think it's horrible that people can talk about a revolution in carnival terms. They want to be heroes and go out and WIN. Infiltration—that sounds like work. That's the hard revolution.

"I told them I thought street violence is now just last year's flower power. They wanted to know about Berkeley so they can imitate it. But the students made me feel as if I was some old creep talking.

"I just think a violent revolution doesn't change a thing. Don't forget the Establishment are extremely well armed."

Over the last year or so, you have been thrust by the press into a position where you are an 'attitude spokesman' for what is happening in the States, which is presumably why you were asked to lecture at the L.S.E. the other day. What exactly happened?

I wound up speaking to a large number of unfortunately misdirected young people.

Who were expecting something political and sociological to come up?

I gave them something political and sociological. The only problem was, it didn't agree with what they thought the tactics for a youth revolution should be. And I can't buy their tactics because I think they're juvenile.

They were sort of trying to bring the Berkeley thing over here?

Yes, much in the same way as they imported "Flower Power".

He showed eighteen minutes of his unfinished film Burnt Weeny Sandwich, sat down on a stool on the stage and quietly asked "Any questions?" Result: total British silence. To start the ball rolling, Frank explained a little about the film excerpt which featured short shots of the Mothers on stage and in recording studio, Motorhead having a fit on stage some eight years ago, and a Keystone-Cops sort of sequence of the group running round the Vienna woods, as the film ran sometimes fast, sometimes backwards. Zappa explained that the film was cut to fit the music, which was from the Uncle Meat album, and that it was part of twenty hours of film he has laying in his basement. The whole thing gave an impression of confusion through use of colour techniques, short shots, and the absence of a plot.

This prompted the first real question of the meeting, when Zappa was asked (inevitably I'm afraid) what the message of the film was. "It is absurd," he replied. A lot of the audience obviously considered it decadent rubbish and couldn't grasp the concept of an absurd film that has been shown on educational television in the States. Right from this point there was a gap between Frank and a section of his audience. The gap should have narrowed as the questions and answers progressed, but it widened instead. [...]

"You are not going to solve all the problems in 15 minutes or ten years," said Frank. "You think if 'we win everything will be great' but who tells you when you're there? The only way to make changes that will last is to do it slowly.

"People are thrilled with the idea of revolution in the streets, it's this year's flower power. Wait for 18 months and there will be another fad. I disagree with your tactics. You won't do it wandering around the streets, you have to use the media. The media is the key and you have to use it." [...]

"It's difficult to sit in front of a group of people who don't like you, don't listen and don't understand what you say to them," said Frank the next day. "LSE is supposed to be a famous college but I didn't get the impression of anything intellectual going on. They seem to be impressed with a lot of dogma. They were making categorical judgements against people not in their peer group. If you don't agree with what someone is saying you should listen to him and try and learn something, or else you're on the way to becoming a fascist. Yes, it is a kind of underground fascism."

I did three lectures at USC, and the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and the London School of Economics . . . and some other schools. And if you want to tell them anything about music, there's never any music students there. Nobody ever ask me anything about music. [...]

It works like this: I get up there and I would really like to talk about music and I'd like to talk about technical things about music. Because I've really got nobody to discuss that with—except a couple of guys in the band. But I get out there and after they ask me the usual stupid questions, like somebody from Seventeen Magazine would ask, like what do I eat for breakfast . . . No! I'm serious! They really do, half to be cute and half to be serious, then they ask me about the Plaster Casters and the GTO's and all that . . . Then, they ask something about the Mothers . . . they want to find out what's our next album going to be like . . . Then, after they get through with the trivial shit, they want to talk about The Revolution. Then, during that section of the conversation they wait for me to give them some sign to go plunging out into the street, and terrorize everybody. You know? It's like, the flower power kids of a couple of years ago got smashed on by the cops, and turned into today's radical revolutionaries now. It's this week's fad. And it's pathetic too. So what I normally wind up doing is saying, "Suppose you guys had your revolution and YOU WON. Like there was a referee there and he said, 'Okay, this side gets it,' And NOW what are you gonna do? What are you gonna do that'll make this country better than it was before? I don't think you've got any leaders that are capable of putting forth programs that would improve the lot of all the people in the United States. You really don't care. What you're advocating, in most instances, is a negative example of what your parents did. You know? 'I hate everybody over thirty and they're all creeps.' What are you gonna do? Kill your mother and father if you win the revolution? You know?

They don't have the answers, And what's more, if they were given control of the country, how are they going to take care of the business of the country? That's the really dismal job—politics! You sit around, and you talk. With a bunch of old farts, all day long, about stuff that really doesn't interest you. That's a dismal job. Who wants that? The kids aren't prepared to do that shit.

June 6, 1969—Royal Albert Hall

What sort of stuff are you into now?

Electric chamber music.

And that's what you're going to play tonight.

Yes, quite a bit of it. That's what we've been doing on the tour and some of it's quite new. In fact five of the pieces were written on the plane coming over, and we've been rehearsing them in our hotel with just the bassoon and the flugelhorn and the clarinet.

So in fact, you're introducing new instruments as well?

Yes.

We drove down from London to Portsmouth to play a show and drove back again that night, then had three or four days to work on the show for the Royal Albert Hall.

The show was very interesting because we did our first ballet. Kansas and Dick Barber were the carriers and Motorhead and Noel Redding were the ballerinas that night!

June 7, 1969—Olympia, Paris, France

Probably the wildest personal appearance ever put on by the Mothers took place during their latest European tour. It was Paris and the audience included Mia Farrow and other celebrities.

"Five Mothers and our German equipment handler were fucking each other onstage, humping and groping in a dogpile of bodies—with their clothes on, though," says Zappa. "It was very bizarre, but like a ballet somehow. The idea is if you do something on the stage that nobody would ever imagine could or should be done, you're helping everybody feel a little freer. Very good therapy. Mia came back afterwards and said she liked it a lot."

This outburst of loving friendship grew from three years of what the Mothers call "packing." Zappa says the process has grown more passionate through the years. Packing consists of anything from hugs or kisses on the ear to a couple of fast forks in the buns and wrapping a leg around another male waist.

"The band really loves each other and they get so physical about it, it's ridiculous," says Zappa. "They'll start packing anywhere now, airports or restaurants. When a new member of the Mothers is voted in by the group, his first few rehearsals must seem pretty weird to him."

The next day we flew to Paris and played two shows at the Olympia. In the middle of our second show, the whole of the cast from Hair came running down the aisles and got up with us. We played "The Age Of Aquarius"—It was a wild show!

June 13-14, 1969—Fillmore East, NYC

We're into electric chamber music. We have some very carefully scored stuff for flugel horn, electric bassoon and electric clarinet, with percussion and things like that. Like, woodwind chamber music with rock and roll time behind it, in a sort of a stretched-out diatonic language. And we've been playing it on the last tour. [...]

We played the Fillmore, and I previewed one of the movements of this new bassoon concerto I've been working on, which is scored for that combination.

A.R., "Mothers Of Invention—Chicago—Youngbloods," Cash Box, June 28, 1969

I like rock. I like to watch you put the Mothers thru their paces, using your entire body as a baton, twisting and shaping the music as the inspiration strikes you. I like to hear your satiric takeoffs on 1950's group rock, and I even like to hear your straight renditions of 1950's group rock (although the loss of Ray Collins' voice takes some of the edge off your vocal group sound). But seriously, Frank. A ballet for electric oboe and bassoon and other woodwinds, with two Mothers leaping around on stage and running up and down the aisles, that's a little too much. (That was the opening number for Friday's late show. Saturday's late show featured a similar, but somehow better sounding version, without the choreography).

If you're going to get into classical music (and there's no reason you shouldn't), let everybody know about it in advance. Maybe you should preplan your programs the way the really big orchestras do, and put big ads in the Sunday Times saying "Come see Frank Zappa conduct the Mothers in anew work for comb, gong and rattle". After all, how would you like it if Bernstein started singing "Sunshine Of Your Love" in the middle of a Beethoven program ?

At their final appearance in New York's Fillmore East, Zappa left a delicatessen supper with famed conductor Leonard Bernstein and found a lovely Swedish road groupie of the Mothers' acquaintance singing to herself backstage.

She had a beautiful soprano voice and Frank promptly told her to join them on the stage and start singing. The lyrics she improvised began along the lines of, "I am making love to the moon flowers," and the whole thing developed into a twenty minute opera with the Mother vocalists joining in and a perfect accompaniment created by the instrumentalists. Many minds were blown that night.

Did you know that Leonard Bernstein was a big fan of yours and every time you played the Fillmore East he came with an entourage to see you perform?

FZ: No. I only met him once when he came to see Chicago, who was our opening act. I was invited next door to Ratner's and I met him there, with the guys from Chicago. He didn't say two words to me; all he did was sit there and deliver a 15 minute monologue on the origins of whitefish. All I know about him is that he's a sturgeon expert.

We flew back to New York [from London] and had about three days off to get over jet lag. Then we played the Fillmore East again and I remember the bill: The Mothers Of Invention, Jesse Colin Young & The Youngbloods and Chicago Transit Authority. Now that was a fuckin' bill. We did that particular bill about two or three times and we actually played quite a lot of gigs with Chicago.

Then we went back to California and had a couple of weeks off that were needed. [...] Then the touring started ove again very heavy.

The End Of The Mothers

Frank Zappa, "tired of playing for people who clap for all the wrong reasons," has dissolved his Mothers of Invention.

The first indication that the revolutionary nine-member band was aproaching the end of its musical career came with an announcement that the Mothers had cancelled all bookings from now until the end of the year so Zappa could concentrate on other projects long in progress. A talk with Zappa revealed the break was more complete than that.

"It all started in Charlotte, North Carolina," he said. "We'd been booked by George Wein on a jazz concert date as bait to get the teenaged audience. We went into a 30,000 capacity auditorium with a 30-watt public address system, it was 95 degrees and 200 percent humidity, with a thunderstorm threatening. It was really horrendous.

"After that I had a meeting with the group and told them what I thought about the drudgery of grinding it out on the road. And then I came back took to LA and worked on Hot Rats (an upcoming solo album). Then we did one more tour—eight days in Canada. After that I said fuck it.

"I like to play, but I just got tired of beating my head against the wall. I got tired of playing for people who clap for all the wrong reasons. I thought it time to give the people a chance to figure out what we've done already before we do any more.

"The last live Mothers performance was in Montreal. The last 'otherwise' performance was a television show in Ottawa the following night"—August 18th and 19th.

Looking back on the

break up obviously makes Zappa feel rather sad. Some members, he says—

for instance Bunk Gardner—are very bitter about it.

"The worst

thing about having a band like that is the responsibility falls on you.

You have to remember, all the time, that the main concern of a

rock-n-roll band is how much money it earns. It's a perfectly valid

stance to take, because these men were earning very little, and some of

them had families—Jimmy Carl Black had five kids.

"So when I'd

announce we had a tour coming up, a few people in a burst of enthusiasm

might go out and spend the money in advance. Then the promoter rings up

and says the tour's off, and someone has to meet that bill, either me or

Herbie (Cohen, their manager, and Zappa's partner in business

ventures). Everybody in the band hated me or Herbie in turn.

"When

I disbanded the group it was as if I'd taken their income away. There

was a lot of mumbling and grumbling. Nobody paused to consider that I

might have been running the band purely on a musical basis. But I would

say during the five years that group was together it was a very good

relationship—we put up with a lot of hardship and misunderstanding."

C: You've said that you're "tired of playing for people that clap all for the wrong reasons." What are the right reasons?

Z: How many words do I get?

C: As many as you want . . .

Z: Well, I'll have to amend that, and say that I think it's okay if anybody claps for any reason at all, these days. When you can see how grim it is out there . . . if you have a reason to clap, go ahead and clap.

C: So you've changed since the time you said that they clapped all for the wrong reasons . . .

Z: Yes, I've changed since then . . . (Jokingly). I was such a bitter person then . . .

C: You're so sweet now . . .

Z: Yeah!

We were on this George Wein jazz tour of this East Coast, with Roland Kirk, Duke Ellington and Gary Burton. We were booked into a hall in South Carolina. Before we went on, I saw Duke Ellington, after all these years in the business, on the same tour with us, begging the road manager for a $10 advance. Swear to God. And the guy wouldn't give it to him. That's like a glimpse into your future.

Concerning the break up of the original Mothers; we had just got back from an East Coast tour, we'd been back about a week when I called Frank to ask him some question or another. We talked for a while and pretty soon he said "oh, by the way—I've decided to break up the band. You guys are now unemployed." I thought that was really cold, but that's the way Frank was. It wasn't a very pleasant experience at the time—we felt we were being very successful and didn't think that was called for, but hey . . .

There was some heavy feelings from the band at the time. It was not the disbandment but the way it was done. I called Frank on the phone for something or another and after about ten minutes of talking, he said that he had decided to break up the band and our salaries (they were really draws, since according to the contract at the time, we all were pardners) had stopped as of last week. It would have been better if he would have given a date, say like six months, and then we all could have made better plans. I felt the same way as the rest of the guys at the time, but didn't hold a grudge against Frank like some of the guys did. I did the later things with Frank, not for him but for myself.

We'd been home about one week, and I got a call from him, on the telephone—it wasn't even in person—on the telephone. [...] We were talking about nothing in particular for about fifteen minutes. You know, just bullshitting. And then he said "Oh, by the way, I've decided to disband the band. Your salaries have stopped as of last week." [...] He hung up after that. I didn't get a chance to react to him. I called the rest of the guys and they said "Yeah, we just got a phonecall from him." Basically did the same thing to them, which to me was very, very cold. You know, not even . . . not even telling you in person.

About a week after we got home, I called Frank to talk to him about something. After a few minutes, he just said, "Oh by the way, I've decided to break the band up, your salaries have stopped as of last week." It was quite a shock! There hadn't been any signs while we were on the tour. [...]

I was the first one to find out, so I immediately got on the phone to Roy. Frank also started to phone everybody but I beat him to the punch with Roy. Then we all started calling each other saying, "What the fuck is going on here?"

When I spoke to Ian, it seemed like he already knew something. I think Frank already had plans for Ian to stay around.

So then we had a meeting, and Herb and Frank did sense that we were a little upset with what was going on with a lot of the business. They kept saying, "There's no money because we're losing all this money!"

[...] At the time, everybody thought that it might have been Herb Cohen who had caused all this crap but we found out later that he was doing just what Frank told him to. Herb became the fall guy! It was decided to pay me and Roy an extra two weeks' salary because we'd been with the band the longest, so that was our little leaving present!

[...] Herb and Frank had been paying taxes on us, so we got unemployment benefits

I believe Frank decided that he wanted to go in another direction.

I think he was just tired of the band, certainly we were criticized many, many times about how badly we played his music. He was very unhappy with certain members of the band. He probably thought it would be less of a drain financially as well, because at that point we were making a salary of $250 a week and I think that was just too much of a drain on him. But, it was his doing and there wasn't much we could do about it. Everybody went their own way—I certainly played with a lot of different bands I around that time.

To explain how that original band broke up is really hard. There are many, many reasons . . . I think Zappa was dissatisfied with some of the performances of the band, the limited nature of some of the people like Roy Estrada and Jimmy Carl Black who couldn't read music—they did play some very complicated stuff, but it just wasn't complicated enough. Zappa wanted the very best sight-readers in the world to read his music, and unfortunately when he got these great sight readers they had absolutely no personality, which is why the band sounded the way it did after that. That's certainly why it looked the way it did, anyhow.

But, who knows what the real reason was in the end? Maybe some of the band were getting laid more than Zappa—I really don't know. But, it was a big shock to all of us, it was like when you've been married ten years and all of a sudden your wife leaves you. It was the same feeling, because we were all of us very close and we'd been doing this for quite a while and . . . it was just a big shock. Some of the guys in the band were so hurt that they never spoke to Zappa again, other than legally anyway. Myself and Ian Underwood appeared in the next two bands, although after a certain point I just couldn't take any more and I left.

For one thing we'd been touring such an awful lot and sustaining huge financial losses. One of the other problems, my attitude was getting very sour because we were working places where it just seemed like I was banging my head against the wall because we had developed the music of the group to a stage where it had really evolved. We could go on stage and we didn't need to play any specific repertoire. I could just conduct the whole group and we could make up an hour's worth of music that I thought was valid.

On the spot it would be spontaneous and new and interesting. It would be creative because the personalities of the people in the group just as much as their musicianship but you stick that in front of an audience that wants to hear songs that are three minutes long and with words about boys and girls in love. It just doesn't work.

No matter what you do instrumentally, get those words about the boy that falls in love with the girl or the girl that leaves the boy—that is the real world!

Anything that is apart from that is not rock and roll. It doesn't belong in their teenage concert halt. It's not something that they can identify with easily. So nobody knew how to take the band. They didn't know if we were Spike Jones with electronic music or whether it was serious. Or what it was.

I just got tired.

[...] At first [The Mothers] were extremely angry at me for breaking up the band. Not because they wanted to play the music but because I had been supporting them. Suddenly I had taken away their income, I said to them: "Look, am I supposed to kill myself going out and doing this over and over again? Well, it's not fun for me anymore." I was really depressed about it. I couldn't do it anymore.

The discontent within the band was later voiced by Lowell George: "The band at that time was very much like the Lawrence Welk of rock'n'roll. Frank wrote all the charts. Everything was very prescribed. There was no room at all for any emotion. The band felt very hurt and ripped off because Frank was living in a $100,000 house in Beverly Hills and they were all still down in the valley. Frank would write piece after piece after piece and they would all have to play it exact. They were hurt by the fact that he was making more money, but more than that they became more alienated by the fact that he would overwork and become totally inhuman." [NME, February 1, 1975, "This here's LOWELL GEORGE," "excited gibbering," by Pete Erskine.]

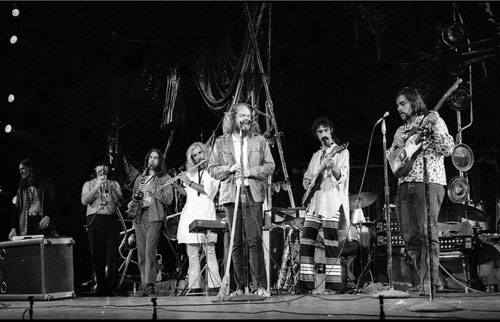

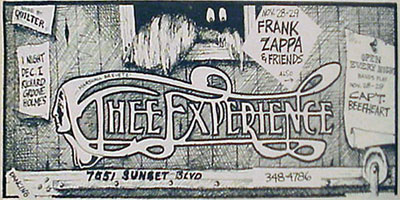

September 22, 1969—Jean-Luc Ponty & George Duke Trio with FZ at Thee Experience

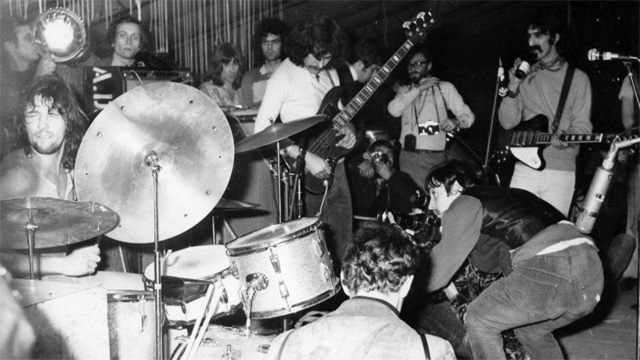

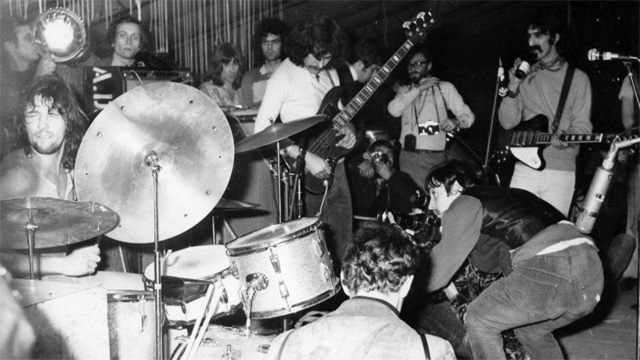

Violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, right, with Mothers of Invention leader Frank Zappa and unidentified drummer join together to unite jazz and rock.

[...] Well, such a mixture occurred last Monday night [September 22, 1969] at L.A.'s newest *in* music refuge, Thee Experience (7551 Sunset Blvd.) and it couldn't have been more successful. World Pacific Records, in a calculated risk, decided to book Jean-Luc Ponty, their contemporary king of jazz violin, into a rock club . . . among rock acts, and see what kind of audience reaction he'd receive. Would you believe . . . standing ovations?

Ponty, looking all the part of a young, French choirboy with violin in hand, was a visual contradiction in himself. So was his music. Quite ably backed by the George Duke Trio (piano, bass, drums) Ponty utilized his violin like a guitar, eliciting bursts of staccato that quickly blended into crescendos of controlled feedback . . . then into softer, more delicate things. [...]

Toward the end of the set, Ponty was joined on stage by Frank Zappa, head Mother of the group that announced this week that they'd be suspending all concerts until the first of the year (they're not, contrary to popular belief, breaking up). As it turns out, one of the reasons the Mothers are resting is to give Zappa time to work on various individual projects.

[...] Ponty and Zappa proved that night that guitar and violin are not such strange bedfellows.

Following Ponty's set, the whole irony . . . the recurring enigma of the music industry presented itself again as the Iron Butterfly, currently America's best-selling rock (and I use the term loosely) group took the stage to do a special hour tour de force of their platinumed recording, "Inna Gadda Da Vida." It seemed almost sacreligous to have them even on the same stage that Ponty used. But . . . that's the music biz.

Pete Senoff, "Thee Experience, Los Angeles," Cash Box, September 27, 1969 (as printed on the cover of Jean-Luc Ponty, The Jean-Luc Ponty Experience With The George Duke Trio Recorded In Hollywood At Thee Experience, Pacific Jazz ST-20168, 1969)

People both in and out of the industry keep trying to put labels and categories to the new, fresh types of music that are emerging continuously via records and live performances. All music, according to them, must fit into a certain mold and stay there. No cross-pollination allowed!

Well, such a mixture occurred last Monday [September 22, 1969] night at Thee Experience and it couldn't have been more successful. World Pacific Records, in a calculated risk, decided to book Jean-Luc Ponty, the contemporary king of jazz violin, into a rock club among rock acts and see what kind of audience reaction he'd receive. Would you believe . . . standing ovations?

Ponty, looking all the part of a young, French choirboy whit violin in hand, was a visual contradiction in himself. So was his music. Quite ably backed by the George Duke Trio, Ponty used his violin like a guitar, eliciting bursts of staccato that quickly blended into crescendos of controlled feedback . . . then into softer, more delicate things. The Trio, led by pianist George Duke, were extremely exciting (playing double-time most of the evenig) and went a long way in contradicting the death of jazz.

But the spotlight was on Ponty. His sound is inmediately reminiscent of Stephane Grappelly, the violinist for Django Reinhardt. But whereas the former was largely relegated to backup chores, Ponty clearly was the lead player on stage. He amply demonstrated his flair for improvisation; the several high-registered codas he emitted from his instrument immediately got the audience, who sat very quietly through his opening number, onto their feet and dancing. They didn't look at Ponty's music as jazz or jazz-rock or any other forcefed label; it had a good beat, was unusual and exciting, and was done with taste. That's all that mattered.

It's significant to note that Thee Experience, unlike most other rock clubs, has an audience made up mostly of musicians. Hence, the ovations Ponty received were doubly-justified.

The set closed with a jam, with Frank Zappa on guitar. It was avant-garde, to say the least.

People ask about the disappearance of enthusiasm in pop music. Well, Ponty attracts enthusiasm and excitement like a magnet.

Jean-Luc Ponty, The Jean-Luc Ponty Experience With The George Duke Trio Recorded In Hollywood At Thee Experience, Pacific Jazz ST-20168, 1969, liner notes

Producer: Dick Bock [...] · Jean-Luc Ponty—Electric Violin · George Duke—Electric Piano · John Heard—Amplified Bass · Dick Berk—Drums

Jean-Luc Ponty With George Duke Trio

Jean-Luc Ponty (electric violin, baritone violectra) George Duke (electric piano) John Heard (electric bass) Dick Berk (drums)

"Thee Experience", Los Angeles, CA, September 24, 1969

[...]

World Pacific Jazz ST-20168 The Jean-Luc Ponty Experience

Baldhard Falk had tipped me off that Jean-Luc Ponty was coming to Los Angeles to record. [...] Many good things happened as a result of these sessions with Jean-Luc.

Actually, we recorded an album at Donte's Jazz Club first. [...] That record was recorded in March 1969, but was not released until many, years later.

Dick Bock, the owner of Pacific Jazz Records thought it would be great for us to record the same music in a rock club. Jean-Luc was not hot for the idea as I remember, but eventually said OK. I was really into playing the piano then, and requested to Dick that they have one there for me to play. Having grown up in San Francisco during the Height Ashbury days, I had been to many rock clubs that had no piano available. Dick promised me there would be one there.

As fate would have it, when I arrived at the gig, there was no piano! The only thing I saw was a silver top Fender Rhodes. I was pissed. Dick had invited all the LA heavies, so, I knew I had to be on anyway. Jean-Luc and I had developed a buzz on the West Coast because of our high intensity progressive jazz style. Dick Bock was convinced that our brand of jazz could get over to an opened-minded rock audience. He was right! I took on the challenge of playing the Fender Rhodes with ferocity. The date was September 27, 1969. The drummer was changed, for what reason I don't remember. Dick Berk was the new drummer.

In attendance were Frank Zappa, Quincy Jones, Gerald Wilson and Cannonball Adderley to name a few. The club was packed! By the way, the name of the club was "Thee Experience."

The first time I met Frank was when he produced the King Kong session for Jean-Luc Ponty. I was working with Jean-Luc at a club in L.A. called Thee Experience, and he insisted that he didn't want to do the record unless I came along with it. He didn't know Frank at that time, so he wanted somebody from his camp to be there. So I did the date, Frank liked me, and it went from there.

[Jean-Luc Ponty] gave me my first shot in the business. I'd sent him a tape and eventually he decided, let's give the kid a shot. I came to L.A. and through working with him I met Quincy Jones, Frank Zappa, and others who would come to see this fabulous violinist, and I just happened to be there playing piano. Now, I knew instinctively that I needed to draw some attention, so I went kind of nuts. I played with my feet. I did everything, because I realized the music business was out there in the audience.

You heard Jean-Luc on the radio and then you chased him down, right?

Yes, they used to play him on KJazz in San Francisco. I had started working with SABA Records and Jean-Luc was on the same record label so I had a couple of his albums. I love those records. And one of the guys from SABA Records told me, "You know Jean-Luc is coming to Los Angeles to make a record. Maybe you can get the gig." I found out who his producer was gonna be and I must have bugged those people to death. They finally just said, "Let's give the kid a shot to get him off the telephone."

We had already started playing at places like Dante's and we had already done some gigs with my trio, the same trio that played with Al Jarreau: John Heard on bass, Al Cecchi or Dick Berk on drums, depending on the night, and myself. So we started doing these dates and Dick Bock, who was Jean-Luc's producer, said, "With the kind of jazz that you guys play, I think that you can get over to a rock audience. So I would like to put you at a club called "Thee Experience"," which was the premier rock club in LA at that time. Jean-Luc was unsure about doing it but I thought, What have we got to lose?! If the audience doesn't dig it then we're out. So Jean-Luc finally said, "Okay if you want to do it I'll do it."

So they booked us in there one night and Dick said, "All you have to do is play the couple of tunes you always do but put a rock beat behind it." And that's what we did. He recorded that night and that came out as "Jean-Luc Ponty Experience with George Duke". There it was. I had said to Dick, "The only thing I want is, make sure there's a piano in there, not one of those little short sawed off Fender Rhodes." I went in and that's all that was, a little sawed off, silver top, 73-key Fender Rhodes. And I was like, "Man, what am I gonna do with this thing?" However, I found out that I could make it louder, I had tone control, I had vibrato. And I was like, "Shoot, I can play as loud as a drummer now!" And that's what happened, I began to dig the instrument. I found throughout all the clunks that I could get some other tonalities and it kind of interested me.

Is this the first time you had played the Rhodes?

No, I had played the Rhodes with Don Ellis. I joined the Don Ellis Big Band for a while. I was pretty comfortable playing a lot of odd time signatures. But working with Don Ellis, who a lot of people probably don't remember, I got bathed in the waters of time signatures. It was an amazing experience. Jay Graydon was in that band, and Ralph Humphrey, who eventually wound up in the Zappa band.

October 24-28, 1969—Festival "Actuel," Amougies

[Aynsley Dunbar, Alex Dmchowski, FZ.]

Frank will be bringing Beefheart over to Europe for the BYG pop and jazz festival this weekend, and says that he hopes to bring the Captain and his Magic Band to Britain for a press reception.

"Beefheart's operating at a disadvantage at the moment," he said. "One of the lead guitarists hit the bass player in the mouth and broke his dentures.

"So the other lead guitarist smashed Jeff's ribs and put him in hospital. Then the whole group got together, got Jeff [Cotton] out of hospital, bought him some clothes, and sent him back to the desert.

"Now one guitarist—Zoot Horn Rollo—is playing both guitar parts, which are very intricate. I don't know how he does it."

I asked Frank about the Actuel Pop and Jazz Festival in Belgium, from which he had just returned.

"I guess it was more of a political than a musical success. The festival was moved around so much that it was a triumph to get it on at all.

"It was so disorganised that when all the lights and amplifications worked on the first night, the organisers looked at each other in amazement. They couldn't believe that it was really going to happen.

"But I was there. Six to 12 hours a night, I was there.

"It was very difficult because it was so cold, and in that temperature several things happen to musical instruments: guitar-players' fingers get cold, which makes it hard to play, and the strings go out of tune at different levels."

Did any of the groups or musicians impress him?

"Yeah, I really like the Nice. They were good musically, and they've got a very exciting stage act, too. And I dug Colosseum—particularly Dick, the guy who plays tenor and soprano. Does he do sessions in London? He ought to—he's really a bitch."