The Rehearsals

I'm getting more rehearsal time for this piece than I expected. It still isn't enough, I don't think, but they've got six rehearsals laid out, which is heavy business.

The only problem is that they're still rioting at UCLA. That may cancel it. We're playing—it's supposedly being held at UCLA in the Pauley Pavilion, which is an 11,000-capacity basketball dome. [...] I wouldn't say [Mehta is] obviously excited. He's going along with the gag.

I met Bill Kraft of the percussion section. They have a very difficult job to do. I also know—what's his name?—Kurt [Reher], who is—I don't know whether he's first cellist or what. He was on the Freak-Out! album—one of the cello players on there. I bumped into him. I haven't talked to any of the other orchestra members. They have to bring in some people from the outside, though, to augment the orchestra in order to do it. Emil Richards is joining the percussion section. I've got to go over to his house because he's got that exotic collection of gongs and weirdness, and he said he'd supply any of whatever—to bring down.

This other guy that I worked with, and who I like very much is John Rotella. He's going to be playing the baritone and bass sax parts, and Ernie Watts is playing the alto and tenor part of the orchestra. [...] I've got one more extra added attraction—do you know George Duke? He's going to be playing the celeste and electric piano part with the orchestra. I like his playing very much.

[The entire piece runs] two and a half hours. [...] We're doing movements one, three and four. Movement three is only one page long, but it's a special system that's got a lot of choreography in it—a special deal. The second movement is this big dramatic movement with a chorus and the dancers and vacuum cleaner and all that stuff. That was too expensive to do, so they couldn't put that in. [...] I've been writing this for three years. It's based on sketches and material that were actually completed on the road or in motels, for one reason or another, and then the final orchestration was done in my house over about three months, just prior to Christmas last year.

All I'm interested in doing is hearing what the music sounds like that I wrote in those motels. If I can hear it, then I can write some more. [...] The way I see it is that finally after all the years that it took me to write this thing, I'm going to get a performance of this piece of music. It's not what I'm doing now, you see. That's what I did then. I just want to hear what I did then.

There's no way to tell who is going to show up or if anybody is going to show up for that thing. There are so many other problems involved in it, like for instance acoustic problems. That place is very dead acoustically. You have a 96-piece orchestra and you have a 9-piece electric band. We're louder than they are when we're soft. I mean, just any electric group—an orchestra just ain't loud. That's the worst thing about an orchestra. And so they're miking the orchestra. That means there's going to be about maybe twenty mikes on the orchestra and those microphones are also going to pick up our amplifiers, because we're set behind the orchestra. Two of the six rehearsals that we have are just to balance the sound. Now if that works out and you can actually hear what's supposed to come out, then we'll be lucky.

I wanted to record it, but it would cost a lot to do that. The only way that it will get recorded is if somebody wants to do a TV special on it. They're trying to sell it to the networks. If they can get somebody on a network to say "Yes, we want this," then they'll record it. That will be their big reason for spending the money. But otherwise, the union scale to do that is just horrible.

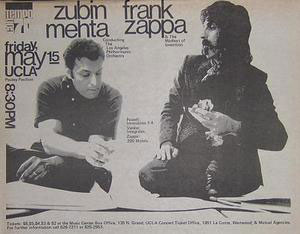

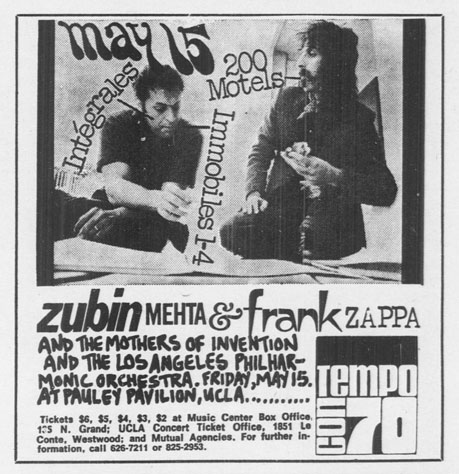

Last month's somewhat abortive "Switched-On Symphony" television program [...] seemed to have whettled the appetite of Zubin Mehta of the Los Angeles Philharmonic who, three weeks after the program, has decided he wants to try a similar occurence live.

With the Mothers of Invention.

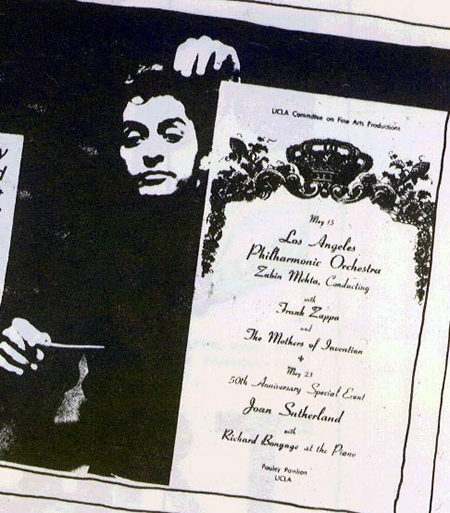

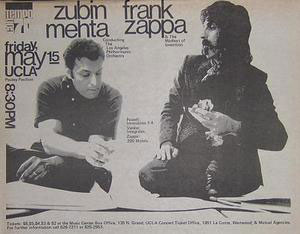

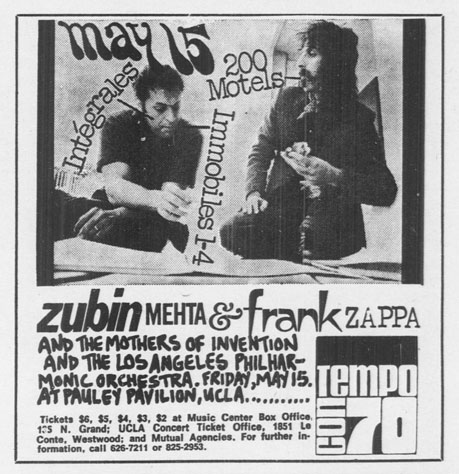

So, on May 15th at UCLA's Pauley Pavilion, Zubin and the boys in his band will be joined on the same stage with Frank and the guys in his group . . . the original Mothers.

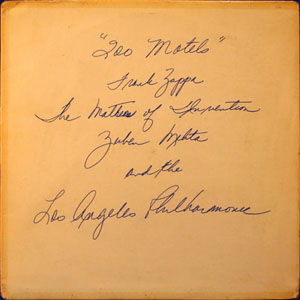

The main work to be presented and performed jointly by the two musical aggregations will be "200 Motels," a work commissioned from Zappa by the committee of the Holland Music Festival. The title stems from a continuous collection of "absurd things" Zappa has thought about in motel rooms prior to and after Mothers concerts. The final presentation (perhaps literally) on May 15th will include such components as: symphony orchestra, narrator, soprano soloist, dancers, a film on dental health, an industrial vaccuum cleaner and a 16mm projector.

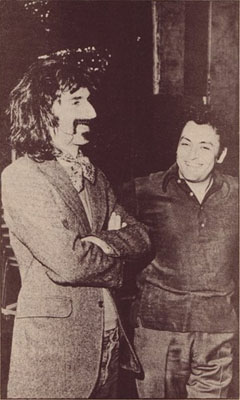

FRANK ZAPPA—with Zuban Mehta, the classical conductor who gave Frank a big chance.

George Duke

Maybe two months [after the King Kong sessions], I was at my mother's house in Marin City, and one Sunday afternoon I got a call from Frank. He asked me to come down and be a part of this show he was doing at UCLA with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta, and the Mothers Of Invention.

After we did the King Kong record, Frank asked me to join the band. I did one date with Frank and an orchestra at UCLA in 1969—with the band that wound up being the Mothers of Invention during 1970.

Don Preston

There were two separate concerts we did there with Zubin [Mehta]—I remember one was with Ray Collins, Aynsley Dunbar, Billy Mundi—I also remember Ruth Underwood playing percussion. She sat in the percussion section, and I remember she was so good! That group played some gigs in New York as well. Zappa then formed a temporary group called Hot Rats which featured Aynsley, Max Bennett, Sugarcane Harris and I think Ian.

May 15, 1970—The Concert

There was a recent concert in Los Angeles at a place called the Pauley Pavilion, at UCLA—it's a basketball arena. And it holds 15,000 people. And we filled the place for a joint concert of The Mothers Of Invention and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. Zubin Mehta was conducting. And they gave the world premiere of this piece that I had written over a period of years while touring with The Mothers. It's called 200 Motels, and the reason it's called 200 Motels is because all the sketches were done either in airports, or in the hotel room, or on the planes, or just traveling around. So it's like a musical diary. And they played the first, third and four movements. The didn't do the second movement 'cause it requires a chorus and dancers.

I had an opportunity to have some scores performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and they agreed to a minimal budget for rehearsals and we had a concert in a place called the Pauley Pavilion which is a 14, 15,000 capacity basketball arena, not exactly the place you want to listen to a symphony orchestra, but it was filled to capacity for the concert, and it helped a little bit. And as a matter of fact I saw Zubin just before we went on this tour, he was picking up some stuff at the airport. He says, "Oh yeah. I'll call you, we'll have lunch."

In May 1970, then-music director Zubin Mehta combined forces with Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention for the premiere of Zappa's "Concerto for Mothers and Orchestra" at UCLA's Pauley Pavilion. Zappa infamously kicked things off by yelling, "All right, Zubin, hit it!," sending his band—well, a version of it put together for this concert—and the Philharmonic into a frenzied performance that included bodily noises, confetti and a romp into the audience as well as more serious orchestral themes and a lot of Zappa/Mothers' riffs. (Some of this music ended up in Zappa's crazy life-on-the-road movie "200 Motels.")

Sometime in 1970, I had an offer for a major concert performance of the orchestral music accumulating in my closet. During the M.O.I.'s first five years, I had carried with me, on the road, masses of manuscript paper, and, whenever there was an opportunity, scribbled stuff on it. This material eventually became the score for 200 Motels (based on an estimate of the number of gigs we played in the first five years—forty jobs per year?).

The performance was to be held at UCLA's Pauley Pavilion (a basketball arena seating about fourteen thousand people), with Zubin Mehta conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. A pretty big deal.

There was a 'catch,' though—the orchestra didn't really want to play the stuff—they wanted AN EVENT; something 'unique'—like—uhh, maybe a ROCK GROUP and—uhhhhh—a REAL ORCHESTRA sort of—uhhh—well you know—'rocking out together.' It didn't matter what the music was.

This eventually led to a few problems. First of all, I didn't have a 'ROCK GROUP'—the M.O.I had been disbanded for about a year. Second, there were no parts copied for the scores, and I was being asked to pay for this enormous job (seven thousand 1970 dollars). The third problem was that I wanted some kind of tape of the show, and the Musicians' Union wouldn't allow it. (They didn't do anything when some asshole in the audience ran a cassette and made a bootleg album out of it, but they were promising stern action if I made one for my own use—just to find out what my pieces sounded like . . . but let me slow down here.)

We solved problem number one by putting together an interim one-shot 'Mothers-Of-Invention-Sort-Of-Group.' It did a short tour to warm up, maybe half a dozen dates, and returned to L.A. for the show.

The second problem was solved by me spending the seven thousand bucks on a team of copyists.

The third problem never got solved, and I never got a tape of the show.

It was the most successful indoor concert of the L.A. Phil's season that year—sold out. Somewhere in the mass of spectators were Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, a.k.a. Flo & Eddie.

They came backstage after the show, said they liked it, and told me that the Turtles had split up and they were looking for something to do. The rest is history.

"Most rock groups could not do this sort of thing because they cannot read music," said Zubin Mehta confidently. "Frank Zappa, on the other hand, is one of the few rock musicians who knows my language." As conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Mehta is known not only for his willingness to step in where many Angelenos fear to tread, but for his ability to get away with it musically. In the peerless leader of the Mothers of Invention (Time, Oct. 31), however, Mehta was taking on a man whose main goal in life seems to zap the musical establishment.

ZAPPA (FRONT) & MEHTA

He who lashed last, lashed best.

The odd musical conjunction of the two men also involved 104 stunned members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic gathered for the world premier of Zappa's 200 Motels, written for the Mothers and orchestra. What the concert, held before 11,000 rock fans at the U.C.L.A. basketball arena, mainly proved is that any marriage between rock and the classics is likely to be stormy indeed. As ther Mothers' bassist Jeff ("Swoovette") Simmons said tolerantly of the orchestra: "Those dudes are really out of it, man. It's like working with people from another planet."

There were times when the orchestra players felt the same way about Zappa and his matriarchy. Attired in pony-tail and yellow-striped pants, Zappa started things off himself: "All right, Zubin, hit it." That was a bit brazen and did not go over too well the violins, who outnumber everybody else and use their weight to preserve a little decorum now and then. Nonetheless, when Zubin hit it, they hit it too. When the rest of the orchestra said "Bleep," the violins joined in. When they required to do fey finger snaps over their heads, they complied. When asked to belch, literally, they drew the line and said "Blurp." When percussionist William Kraft, dutifully following the score, fired a popgun, they played on unblinking. Meanwhile, platformed six feet above the orchestra, the Mothers were lullabying away at some of their "greatest hits," like Lumpy Gravy, Duke of Prunes, and Who Needs the Peace Corps. Then, everyone in the orchestra suddenly screamed, one final frightening chord was heard, and with a giant blurp 200 Motels closed down for the night.

No complaints, however, were heard from the Philharmonic management, clearly overjoyed to have got its players into the same hall with that many young people and brought $33,000 into the box office. As for Mehta, if he did not have the last laugh, he at least had the last lash: despite Zappa's protests, he cut out the entire second part of 200 Motels. Just as well, Part 2 calls for a chorus to blow bubbles through straws and the soprano soloist to sing "Munchkins get me hot."

"A

lot ot people said it sounded like movie music," says Zappa. "Well, in a

way it is—for a movie they haven't even seen yet, the movie that I

was living while I was out there on the road touring with the Mothers.

I'd go back there to the motel after a job and write what ever I was

thinking about: it was more like a musical diary, a two-year orchestral

diary. Then the idea occurred to me using this orchestra music with some

songs about life on the road, and then staging some action around it,

and ending up with a sort of grandiose opera for television." Mehta

conducted three of the four movements at the May concert, but because of

cost, the chorus, dancers and most of the stage action had to be

omitted.

David Felton, Rolling Stone, July 9, 1970

In three hours Zappa:

- Introduced the orchestra members to a spirit of freedom they will find hard to forget, punctuating their scores with burps, grunts and adlib confetti throwing. At one point the bass horn player stood up with his horn, twirled around like a drunken elephant and sat down. At another, the entire orchestra walked off stage and into the audience, each member apparently playing his own composition.

- Relentlessly chided Mehta with remarks like, "All right, Zubin, hit it!" and "Now you know the cue where to in, don't you, Zubin?" (Mehta got in a few of his own licks, like warning the audience, "You must no think that this is any way a rock concert . . . this is music like any other music.")

- Subjected the orchestra and audience to a mild dissertation on teenage cum stains that ended with a brutal parody of Jim Morrison's oedipal walk down the "ancient hallway" in which the hero discovers his father "beating his meat' to a Playboy magazine. "He's got the Playboy magazine rolled into a tube and has inserted his member right into a tube and has inserted his member right into the tube . . . Father, I want to kill you . . . Not now, son, not now!"

- Invited members of the Philharmonic to stay for an adlib encore of King Kong, during which cellist Kurt Reher established himself as a master freak and clarinetist Michele Zurkovski had a stuffed toy giraffe inserted up her dress.

Musically, Zappa presented few surprises, since his material has always combined rock and classic elements. His version of Edgar Varese's Intergrales and his own 200 Motels for Mothers and Orchestra included the usual Zappa riffs from Varese, Stravinsky and Gustav Holst.

In general, the sound was terribly distorted, although it did indicate how closely, on purely a sensual basis, an amplified rock band can resemble an acoustical orchestra.

But as Zappa pointed out in his opening statement, "When you play music in a hall designed for basketball, you take your chances."

Outside UCLA's Pauley Pavilion [...] there were lots of lank-haired chicks with nice barefoot dirty feet (dirty bare feet always look cleaner than clean feet that have just been in shoes), lots of fringed buckskin and denim everywhere. [...] There were straights here, too, with children, and wearing suits [...]. The straight Johns were here because Zubin Mehta was going to conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic. This was the third concert in a series by the Music Center, known as Contempo '70 ("20th Century music: How it was, how it is"). The denim, nostalgie de la boue crowd was here because Frank Zappa had re-assembled his Mothers of Invention (disbanded in late 1969) and was going to play. Some other misfits were here, no doubt, because Frank was going to play in concert with the Philharmonic—the world premiere of a two-and-one-half hour composition for Mothers and orchestra (cut to about an hour for this performance), entitled 200 Motels. [...]

Inside, the L. A. Phils could be seen seated at one end of the basketball court and, behind and above them, two electric pianos, Hammond organ, drums, amps and other esoterica of the Mothers, who were to come on later. [...]

Things were late, and at about ten till nine, Zubin Mehta, born in Bombay, India, strode to stage center-facing a crowd, incidentally, that seemed more empathetic in its life style to indigenous Indians than to Hindus. Seeing that considerable of the eventual capacity of more than 14,000 was still looking for its seats, he gave the audience a little lagniappe of Stravinsky. Finished with that, Zubin approached the microphone, found it dead and so repeated the Stravinsky. Then, finding the mike still dead, he borrowed another from a member of the orchestra. [...]

Using the auxiliary mike, Mehta—who looks like a mature Sabu—gave a little caveat to the people: "I want to correct one misconception. Anyone who thinks he's come to hear a rock concert is mistaken. You are all trapped here under the pretext of hearing rock 'n' roll. I dont want any misconceptions—especially with our older patrons. [Laughter] 200 Motels will be a little rock 'n' roll but it's absolutely contemporary music." Zubin then introduced the first selection, Immobiles 1-4 for tape recorder and/or orchestra, by Mel Powell, who was described in the program as "one of the pre-eminent figures in contemporary music." Powell was seated on the basketball floor.

Mehta struck up Immobiles 1-4 and was concluding the second of the four immobiles when there came a deep, urgent voice from the floor: "Zubin! Zubin!" Music stopped and the voice was handed a mike and it was Powell with a bulletin from the front that the tape-recorder part of his composition hadn't been playing since the beginning. After a brief consultation, Mehta announced that he would skip the Powell piece and go into Varèse's Intégrales. Edgar Varèse (1885-1965) has been called the "grand old man of the perpetual avant-garde." He is one of Zappa's models and it was Frank himself who suggested Intégrales be performed. (The general view of music lovers was that the rendition was flashy and hopelessly distorted.)

Now the Mothers entered and climbed to their second-story stage. Eight of them, counting Frank. Ian Underwood on electric piano, doubling on sax. (Program: "An M. A. in music and child prodigy at the piano.") Ray Collins (an original Mother, going back to Freak Out days) with wild titian hair, playing the tambourine and singing. James Motorhead Sherwood, "sax and other things." Zappa—slim, but mesomorphically muscled—resplendent (for him) in lime and yellow horizontally striped hip-huggers that fit his impudent buttocks like wool jersey, topped with a purple long-sleeved T-shirt. Mother Motorhead (who has "teen appeal," according to Frank) was attired in a white letterman sweater with three varsity stripes, and beneath that a kelly-green Fillmore East T-shirt—his lengthy hair tied with a ribbon in the back, giving him the effect of a rather prognathous member of the Girls' Athletic Association field-hockey team. Zappa's golliwogg hair was similarly tied and he displayed the trademark Zappa-ta facial hair, which somewhat resembles the silhouette of an explosion over Eniwetok, beneath that splendid banana nose.

A little speech by Zappa: "We're kind of tense . . . the tape recorder breaks down. When you play music in a hall designed for basketball, you take your chances. Maybe some day, if music becomes competitive and violent, they'll have halls this big designed for music . . . . Will Don Preston, our organist, please stop vomiting and come up on the stage?" (Program: "Don Dewild Preston—all keyboard instruments and weirdness—joined the group in the summer of 1966. He plays the Monster in the forthcoming Mothers' movie, Uncle Meat.") The Mothers opened with an old Angels' nifty (Ooh-lah-dee-lah), My Boy Friend's Back and then, without intro, segued into their version of Intégrales—which, well . . . sounded like Varèse's work in some spots.

Then Zappa, putting it to the Dorothy Chandlers directly beneath him, launched into an original recitative, which embroidered on an Oedipal refrain ("Father, I want to kill you!") sung by Jim Morrison in The Doors' The End:

You're uptight. Sitting all alone in your teenage bedroom. You're tense. And you got . . . to . . . go . . . get . . . your cookies! Around the wall are little cutout decals of sailing boats, donkeys and Little Bopeep. You're lying in your flannel pajamas in your teenage sheets—all you mothers out there know what teenage sheets are; they're the ones with the yellow and brown stains. You tiptoe through the living room to the kitchen to find the cookie jar—your favorite oral gratification: oatmeal raisin cookies! They're in the Aunt Jemima cookie jar. You rip her head off and stuff your sweaty teenage hand into her body. You grab a cookie—tempting raisins, a fascinating tactile sensation—you know you're gonna get off on it. You go to the icebox, open the door, take out a box of milk and pour it into your drinking hole.

But he still hasn't quite got it off. He then goes into his mother's room and cries, "Mother, I want to kill you!," but she ignores him, being too busy putting silver and green and blue stuff around her eyes. And anyway, she knows where he's at. She's washed his sheets. He goes into his father's room and makes a similar death threat, but his father, busy masturbating, ignores him, too.

The Dorothy Chandlers seemed unperturbed by how near the knuckle this struck, and then the Phils below, in a little arch-Happening, walked off, blowing discordant sounds. In rebuttal, Frank directed the band to hit different notes, and on about the fourth one, came up with his middle finger extended, while the Mothers screamed "Aaaah!" as if they'd been goosed. The Battle of the Bands was on.

[...] The Phils and Mothers returned and Frank took the mike to say, "Mr. Powell has left and he took the tape with him." (Martin Bernheimer, Los Angeles Times: "[Powell] later explained his action in terms of 'revulsion at the wretched debasement of new music . . . exploitation of pop mobs . . . mockery of art . . . cynical attitude of the Philharmonic management. Powell insisted his displeasure had little to do with the musical mishap. He also claimed that Ernest Fleischmann, executive director of the Philharmonic, attempted to bar his exit, threatening never to schedule his compositions again. Fleischmann dismissed Powell's behavior as 'ridiculously unprofessional.'")

Zappa then gave a brief preamble to 200 Motels: "I wrote this a while ago when I thought symphonic music was where it's at, and when we rehearsed this week, I heard all the errors I made, but we left them in—so you're gonna hear them too. It's not really a great piece of music, but I think we can get off a few times." (200 Motels represents strains and snatches written by Zappa in motels and hotels here and in Europe on his road trips. The whole mother is two and one half hours long, but one sequence, which required, among other things, a soprano soloist, three dancers, a chorus, a narrator, an industrial vacuum cleaner, a noisy 16mm projector and a dental-health film, was deleted, cutting this performance to about an hour.)

"All right, Zubin, hit it!" cried Zappa, initiating the world premiere of 200 Motels. What really happened, as it developed, was not two bands playing together but two playing apart—a battle of the bands. And here, the Mothers' superior decibel energy gave them the edge. A good eight-piece hard-rock group with their Fender Stratocasters peaked and their fuzztones stomped into action can make a 100-piece symphony sound positively puerile. As to the flavor of 200 Motels, it was eclectic, to say the least. It began with a good, harddriving rock passage and then segued into a leitmotif that soon began to be identified, each time it came round, as "Brigitte Bardot '57." Then the Phils came in with an atonal passage, during which the Mothers—having a 75-bar rest, or so—insouciantly lit up Winstons. Other echoes that could be caught throughout the piece: Dvořak's New World Symphony, Victory at Sea (Guadalcanal March and Beneath the Southern Cross), Debussy's Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun, Copland's Appalachian Spring, Thomson's The Plow that Broke the Plains and honky-tonk jazz. All this was punctuated by Zappa telling the audience, "Laughing is very easy, all you have to do is go 'Ha-ha-ha!'" followed by nearly 14,000 risible patrons doing just that; Mother Motorhead making yodeling sounds; a little soft-shoe in unison by the Mothers; a voice from the upper deck intoning a mighty "Ooooaaaah!" followed by Zappa yelling, "Shut up, you idiot!"; a member of the symphony brass tearing his music to shreds and throwing it into the air, followed by the string section crying "Barf!" (Could this be the promised "bodily noises"?); the Phils and the Mothers exchanging friendly insults, topped off by Zappa crying, "Horseshit!"; the Phils goofing a few bars, with Mehta apologizing with a big operatic shrug to Zappa; Mother Ray holding up a toy giraffe, which then gave birth to a rubber chicken; some flickering blue flash bulbs on the jungle gym that held the stage lights (a sort of dime-store light show); a UFO gliding down from way up above—turning out to be a glow-in-the-dark Frisbee; a sequence in which only one Mother played and the others faked it silently.

During all this, the audience seemed attentive but not really turned on—not exactly the kind of concert where you need 500 rent-a-cops to keep things in order. At the end of 200 Motels, there was a minute or two standing ovation—although one cynical critic suggested the ovation might have been prompted by the audience wanting to hear the Mothers in encore.

So they did. Zappa announced to the Phils: "Any of you fellows who desire to play rock, join us—you'll not get any overtime—and we'll play our version of King Kong." Eight or ten Phils (all of them young) brought their axes up—mainly brass and reeds, including one awkward bassoon. Zappa: "When I go like this, horn players pick any note at random, attack it and swell it up. We need a cello. [An obliging cellist walks up.] It's a very simple melody. Key of E-flat minor for as long as you can take it." The session began with the bassoonist starting oil a little badly by bumping Mother Motorhead with the swan's neck of his instrument—but then, in later passages, coming on so strong that there is no doubt that, if they ever get this on LP, you'll hear one of the great bassoon riffs in rock-symphony history.

"I think that most of the members of the orchestra didn't like doing the Zappa concert," said Mario Guarneri, a USC music graduate of 1964 who plays trumpet. "You must realize that many of the older members have been trained very rigidly, and the Zappa concert didn't go over well with them."

"Many members of the orchestra were shocked that Zappa would say what he did on stage," said [Mickey] Nadel. "I don't think anyone objected to the music that Zappa wanted to do, but they simply were shocked at his act.

"Zappa practiced with us for one whole week without letting us know what he was really in to. He didn't make any trouble and did exactly what Mehta told him to do, but when he got on stage with the rest of his group all hell broke loose."

Zappa's performance was punctuated with profanity and gyrations. It was certainly a change in concert music. but it didn't work out as well as it might have.

"I think everyone knew that Zappa was a talented person, but actually his '200 Motels' isn't much more than a collage, a collection of strung-together Zappa hits. He really doesn't get into any development, but then, I don't think that he pretends to be a concert composer," Nadel said.

It's hard to judge the value of the Zappa concert, but the fact that it even took place is important.

"Most of us in the orchestra were impressed with Zappa," said Nadel, "and he was very much impressed with our first cellist and asked him to tour with the Mothers of Invention (Zappa's music group). When Zappa asked some of the members of the orchestra to jam with him on stage after our concert, some of us did."

"It was more of a happening than anything else," said Mehta. "We didn't do a completely rock concert, though. We played little bits of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, among other things. But basically it was a concert dedicated to the premiere of Frank's piece and it was, I suppose, successful.

"Frank Zappa is, I think, one of the most sincere musicians in the sense that he is practically self-educated. He has really done it out of his own desire. Nobody pushed him towards it. And for that reason it was enough to do this guy the honor of playing his work."

FZ, interviewed by Bill Gubbins, Exit, May, 1974

You know, it cost $7000; it cost ME $7000 and I wrote it, to get the parts copied for that thing that we did with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Before that orchestra could play my music, I had to spend $7000 to get somebody to make parts for it. And they got used once! So that's what you get if you write for an orchestra.

When we do things . . . like the introduction to Call Any Vegetable is the opening part of Agon by Igor Stravinsky. Nobody recognizes that. We played it at that concert in Los Angeles with the Philharmonic—Zubin Mehta didn't recognize it! And we're playing it exactly off the score; we voiced it out, the exact same things that are on the page, there's nothing left out, just that it's being played by electric instruments. The only person that knew that we played Agon in L.A. was Lalo Schifrin. Nobody in the orchestra even recognized it.

[...] I felt it was [a success], definitely. First of all, 14,000 people showed up by actual box office; that's the reports that I got. No press since that event has given an accurate accounting of what the box office was. They intended selling 11,000 tickets. That would have been 11,000 seats where everybody could have seen the stage, and 3,000 more people than they expected showed up. And those people, like some of them were press people, were sitting behind the orchestra. The orchestra in a place that big had to be amplified and the speakers are facing toward the far end. We were about 12 feet above the orchestra on a platform, and the only thing that I could hear was the percussion section, which was right at my feet. And we were amplified; not just our instrumental amps, but going out through a PA system, too. So anybody who was behind the projection line of those speakers, God knows what they heard. If it was anything like what I heard from where I was standing, it was somewhat incomplete. But at the end of the show, the people just went completely berserk. We got a five-minute standing ovation, and there were people out there who looked like they really dug it, you know, really heard it.

[...] And everything that those people were doing was all written into the score. You know, I didn't just say, "Okay, when you get done, you over here, you make an ass out of yourself this way, and you over there, you make an ass out of yourself that way." It was all part of the musical concept. [...] In the score it says, "horns stand, shuffle decks of cards." Well, in a normal acoustical environment, where you have some resonance to the room, if nothing else is playing and the horn section stands and goes brrapp like that with a deck of cards, it's a sound. But in a basketball arena, it doesn't make much sound at all. And they'd been doing it, but it just wasn't coming off. So, I didn't know it, but they had decided among themselves at that point they're gonna stand and throw the decks of cards all over the violas. And the viola players just went "what?," 'cause all these cards were coming down on them. It was actually great, and I didn't mind them improvising on the score at all.

FZ, quoted in Zappa!, 1992

Well, the case of working with Zubin [Mehta] was all pretty cut and dried. The Los Angeles Philharmonic management thought that it would be a successful concert. They certainly didn't do it because of musical content. Basically, I had to buy the privilege of having my music performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In order to prepare the parts for the orchestra, I had to pay the copying rate, which in 1971 was somewhere between $7,000 and $10,000. I'll guarantee you I didn't make anything like that from the concert. Plus the fact that they wouldn't even let me make a cassette recording of the performance. They told me that if I turned the tape on, I would have to pay the whole orchestra Musicians' Union scale. So they had two rehearsals for all this music, and—you know—it was a festive occasion because there was a rock group onstage and an orchestra playing, and it was being done in a basketball stadium. So there we have it.

When you play music in a hall designed for basketball, you take chances. We were positioned high above the stage and the sound was so distorted we couldn't hear ourselves. When we did, we'd play one note and drown out the whole orchestra. So, generally I wasn't too pleased with it, but the audience spent the entire evening jumping up and down and shouting so they obviously liked it, and maybe that made it worthwhile. What really bothered me most was the attitude of the typical symphony musician. They don't care, they sit back sneering at everything and play whatever's put in front of their faces, without any spirit or drive.

FZ, interviewed by Patrick Salvo, COQ, February, 1974

I think it was successful from a number of standpoints and then a musical flop in some ways. It is virtually impossible to make any kind of music in a basketball arena, and if you're trying to stick a symphony orchestra in a basketball arena that holds 14.000 people and put an electric band alongside of it, any mixer in the world is going to have trouble trying to make it sound like it should. So we just had to struggle with those problems. It drew about 14,000 people: there was a big audience that wanted to see the event. There was no place available that had that seating capacity and better acoustics. That was just the only place we could have done it.

Mel Powell

I've heard stories of that night from many different people—including composer Mel Powell (who stopped the performance of his piece half way through).

Marc Shulgold, Rocky Mountain News, January 29, 2003

Mel Powell [...] once angrily stomped out of a concert his music shared with Zappa and the Mothers.

The Night That Mel Powell Packed Up and Went Home

Mel Powell's "Immobiles 1-4" almost received its local premiere during the Los Angeles Philharmonic's recent Contempo '70 series. The dean of the school of music at California Institute of the Arts has accepted an invitation from The Times to explain his hasty mid-concert withdrawal of the new composition, and to comment on the popular local attempts to fuse symphonic music with rock 'n' roll.

"The very hypocrisy young people abhor is at work ensnaring them, seducing them"

"Pop music . . . is manifestly in the wrong zone when set beside a symphony orchestra"

DS: Speaking of other [conductors] and such, the 1970 concert that you did with the L.A. Philharmonic with Zubin Mehta, I've heard a cheezy little audience tape of that, and at some point, if memory serves me right, there was something that was said from the stage that pertained to the fact that another composer, if I understand this correctly, named Mel Powell, who was supposedly also in that same concert, had gotten pissed off about something, and had just left, an so, his music didn't get performed.

FZ: Yeah.

DS: What's the story behind that?

FZ: He had some electronic equipment that he was trying to hook up, but they had some technical problems with it. I think it was something for tape and orchestra, and he had some problems, and he just got pissed off and left.