March 26, 1965—The Bust

Ted Harp, "2 A-Go-Go—To Jail," The Daily Report, March 27, 1965

Vice Squad investigators stilled the tape recorders of a free-swinging, a-go-go film and recording studio here Friday and arrested a self-styled movie producer and his buxom red-haired companion. Booked on suspicion of conspiracy to manufacture pornographic materials and suspicion of sex perversion, both felonies, at county jail were: Frank Vincent Zappa, 24, and Lorraine Belcher, 19, both of the studio address, 8040 N. Archibald Ave. [...] The surprise raid came after an undercover officer, following a tip from the Ontario Police Department, entered the rambling, three-room studio on the pretext of wanting to rent a stag movie. Sgt. Jim Willis, vice investigator of the San Bernardino County Sheriff's Office, said the raid suspect, Zappa, offered to do even better—he would film the movie for $300, according to Willis. When Zappa became convinced the detective was "allright," he played a tape recording for him. The recording was for sale and it featured, according to police, Zappa and Miss Belcher in a somewhat "blue" dialogue. More Enter Shortly after the sneak sound preview, the suspect's hope for a sale were shattered when two more sheriff's detectives and one from the Ontario Police Department entered and placed the couple under arrest. [...] Assisting Sgt. Willis in the raid were sheriff's vice investigators Jim Mayfield and Phillip Ponders, and Ontario Detective Stan McCloskey. Arraignment for Zappa and Miss Belcher next week will bring them close to home. Cucamonga Justice Court is right across the street from the studio.

The San Bernardino County Sun, March 27, 1965, p. 22

Pornographic films, tapes, confiscated in Studio Raid:

Vice officers raided a Cucamonga recording studio yesterday to arrest a couple and confiscate what was alleged to be a score of pornographic tapes and movies, sheriff's officers reported.

Investigators identified the couple as Frank Vincent Zappa Jr. 24, and Lorraine Alice Belcher, 19, both of whom resided in the firm at 8040 Archibald Ave.

Lt. Edward Noon, commander of Sheriff Frank Bland's vice narcotics said the pair was held for investigation of conspiracy to manufacture pornographic tapes and films for sale and sex perversion.

Detective James Willis acting as a buying customer, allegedly purchased a lewd tape recording for 50 $, minutes before fellow officers moved in for the arrests.

Investigators said the man and the girl were taken into custody as a legitimate rock-and-roll recording session was about to begin inside the studio of Zappa productions.

Ontario police investigators joined Willis and Philip L. Pounders and James Mayfield of the sheriff's staff in the probe.

Lt. Noon said that Zappa had made an statement.

FZ, interviewed by Lon Goddard, Record Mirror, June 7, 1969, p. 12

They got me for conspiracy to commit pornography back in '64, by smuggling a plainclothesman disguised as a used car salesman into my small recording studio in that very small town. The town had about 7,500 people in it and they didn't like my long hair, so they decided to get me.

The attorney was 27 years old and he got me ten days in jail by using evidence obtained from the hidden microphone in his wristwatch which was hooked up to a tape somewhere. There were 45 men in the jail cell, the toilet and shower had never been cleaned, the temperature was 110 degrees so you couldn't sleep by night or day, there were roaches in the oatmeal, sadistic guards, and everything that was nice.

One day, a policeman in duty at the club made a sincere request. Would Frank be interested in making training films for the San Bernardino Vice Squad? As it happened, Frank and 80 hours of tape recordings of assorted friends, freaks, tradesmen, local officials and girl friends, and he reckoned that these tapes with filmed actors could really show the police trainees the people they would deal with as people. He played him some tapes.

Another man turned up at Archibald Avenue. He said he wanted some "hot tapes" for a party of used car salesmen. Could Zappa help for $100? Sure, said Frank, why not? So he went into the studio with a girl friend and they grunted and groaned into a microphone and then Zappa edited out the laughs.

The man turned up again, had Frank got the tape? Yes, said Zappa. And photographers and policemen crowded into the studio: "Hands up against the wall," etc. One policeman broadcast the proceedings through a wrist radio to a van outside like Dick Tracy. Frank was led out, handcuffed. Awaiting trial in jail, Frank was visited by a bail bond man, who told him that he could spend up to 20 years in a mental institution. "That made me feel pretty sad," says Frank.

It turned out that the bond man had got the penal code number of the charge wrong: "Lewd and lascivious conduct" is one decimal point away from "rape of a child under 14." This emerged later. Eventually, Frank was given three years' probation, on the condition being that he could not be with an unmarried girl under 21 except in the presence of a "competent adult." And that is how Frank Zappa, as a convicted felon, missed the draft.

Mark Lundahl, "Frank Zappa Remembers San Ber'dino," The Sun, Baltimore, April 7, 1980

[FZ] also earned money playing cocktail music at the Club Sahara in San Bernardino, the Robin Hood in Fontana, Sinners and Saints in Ontario and several other local bars that have since closed, burned down or otherwise been forgotten.

And he once spent ten days in the San Bernardino County jail [...].

The year was 1964, and according to Zappa he was framed by a "bogus investigation" handled by the sheriff's vice squad. The reason for the action, he says, was that officials wanted to widen Archibald Avenue and evict residents in the way. Zappa's Cucamonga studio was in the way, he said.

"One day, this detective came in and told me he was a used car salesman, and that some of his friends wanted to have a party next Wednesday, and could I make them a movie for the guys.

"So I said, 'Hey, what a humorous idea. Let's get the used car salesmen off.'

"But there was no way I could make a movie for the amount of money he wanted to pay, so I said, 'How about a tape recording for the guys.'

"He said, 'Fine, I'll give you $100," and then he listed all these things he wanted to have included on this tape," Zappa said.

"I agreed to do it because I thought it was a hilarious idea. The very idea that used car salesmen would sit around listening to this tape and be amused by it was concept art as far as I was concerned.

"By the way, the tape (reportedly a mix of bed squeaks, lewd conversation and cheesy music) was no more sensuous than side four of the Freak Out album," he added.

"So he comes back the next day and gives me $50. I said, 'I thought you were going to give me $100,' and before I could say anything else, he flashes a badge, the doors open up, all these guys run in with cameras and start taking pictures of everything, then handcuffs, the whole bit.

"It was just like science fiction. I didn't know what was happening. [...]

"The whole thing was totally illegal entrapment.

"First of all I wasn't aware any laws were at stake. And secondly this man was offering to pay me money and specifically telling me what he wanted to be done, and recording it all on a wrist radio which was broadcasting to a truck parked outside," he said.

"So they took me to court, and I didn't have enough money to fight the thing. I had to plead nolo contendre.

"They were going to drop the whole thing, but there was this 26-year-old assistant district attorney who insisted that I must be punished and I must go to jail.

"So they gave me a six-month sentence with all but ten days suspended, plus three years probation," he recalled. [...]

"When I was arrested they confiscated all the tapes in my recording studio, purportedly as evidence. Then when the trial was over the detective came back to me and said, 'If you'll let the sheriff decide which of these tapes are obscene, we'll give you back all the rest of them erased.'

"I told them I was not in the position to convert a sheriff into a judge.

"And they never did give them back to me. Eighty hours of musical recordings were never returned. It was grossly unfair. I tried to get the ACLU to help me, but they told me the case wasn't big enough. They wouldn't touch it. Since that time they've come to me and asked for donations and asked me to do benefit concerts, which I have refused to do."

[...]

"I do remember that when I was in jail, I was served this bowl of Cream of Wheat. When they handed it to me, the Cream of Wheat fell out of the bowl in one big lump, and imbedded in the bottom of it was a cockroach this big," he said, spreading his thumb and forefinger two inches apart.

"So I took the cockroach out, saved it and put it in the envelope of a letter I was sending back home. The jail censors got it, and then they put me in solitary confinement."

FZ, interviewed by Kurt Loder, Rolling Stone, 1988

So here I am living in this studio, and living there with me were two white girls and a black baby. [...] And in order for me to earn a living—since there weren't surf bands beating down my door to record yet another "Wipeout" there I worked on weekends playing guitar at this barbecue joint in Sun Village, up near Lancaster, seventy-five miles away. I got seven dollars a weekend only job I could get. Anyway, while I'm up there doing my gig, apparently, these two girls had gone out in front of the studio and were playing on the street with the black baby—which offended all parties concerned in this little village. So, the next thing I know, I got this guy knocking on my door saying he was a used-car salesman—saw the sign, they're having this party and can I make an entertaining movie for him? [...] To me, it was a fuckin' joke, okay? I mean, the minute the man started talking about "oral copulation," I should've gone, "Huh?" But, no, I didn't. Because remember, I was making seven dollars a weekend up there in Sun Village.

I was flat broke and couldn't afford a lawyer. I phoned my Dad, who had recently

had a heart attack—he couldn't afford a lawyer either. He had to take out a

bank loan in order to bail me out.

Once I got out, I went to see Art Laboe. He had released some of my material

on his Original Sound label ("Memories of El Monte" and "Grunion

Run") and got an advance on a royalty payment, which I used to bail out

the girl.

In the case of "Grunion Run," although there was never a complete accounting,

when I needed money, the time I got arrested in Cucamonga, I went to Art Laboe and he gave

me an advance of $1,500.

An officer of the law casually asked Frank whether he'd be interested in making some training films for the San Bernardino vice squad??? "It was a great chance to do something interesting for the education of those people," said Frank. "I thought to myself, 'Now look, these guys are always going around and busting these weirdos and they treat 'em bad but that's probably because they don't understand. They don't know that these people they're arresting are really people." Frank to do the film using the real personalities themselves—hookers, dope fiends, assorted pervs—cinema verité.

The policeman presented his card and vanished.

[...]

Explains Frank: "The California penal code works it out this way: a crime is a crime. If it's a misdemeanor, it's a misdemeanor unless you talk about doing a misdemeanor with somebody else. If you discuss it with somebody else, it's a conspiracy, which means it's not a misdemeanor, it's a felony."

[...] Frank's father bailed him out by taking out a bank loan. Frank bailed out his buxom red-haired accomplice after going back to L.A. and wrangling the residue of the royalty money he'd been owed for a tune he wrote with Ray Collins called "Memories of El Monte."

[...] The trial came next . . . Frank hired an esteemed lawyer for $1,000 who "sort of sold me down the river to a twenty-seven-year-old DA who was really a prick. He just didn't like me, no matter what." Even when the evidence was thrown out, even after the charges had been reduced to nothing, the DA persisted. While the pre-trial hearings were underway, the vice squad had listened to all the tapes to determine what was obscene and what clean. Frank got back about thirty hours of tape after the hearing. The rest still sits in San Bernardino.

[...] Frank got off with ten days in jail and three years on probation—during which time he could not be with an unmarried girl under twenty-one except in the presence of a competent adult. But being a convicted felon was also his way out of the draft.

[Motorhead's] mother had given Frank a place to stay after his fall from parental grace in the Cucamonga Porn King Incident.

Frank's father had to take out a bank loan to pay for his son's bail. Once out, Frank contacted Art Laboe, owner of the Original Sound label, and obtained a $1,500 advance against the royalties for "Memories Of El Monte" and "Grunion Run." This he used to bail out Lorraine Belcher and to engage the services of an attorney.

His criminal record was erased after a year, which is why researches have found nothing in the records relating to the case, but it exempted him from military service. [...]

Frank's father was so incensed by the affair that he refused to let his son return home. Motorhead's mother took him in while he figured out what to do with his life.

Molly R. Okeon, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, May 3, 2005

Just after the bust, a photo published in what was then the Ontario Daily Report showed Zappa and [Lorraine Belcher] Chamberlain smiling, their arms draped around one another.

"If you look at it, it looks like they're posing for the picture and smiling like they're really proud of what just happened," [Derek] Miley said.

In fact, Chamberlain explained, it was just an odd coincidence. After officers had separated the couple to question them, Chamberlain insisted on being reunited with Zappa. Once back together, Zappa apologized so profusely that the two burst into laughter and embraced, she recalled.

At that moment, a news photographer kicked open the door, which turned the couple's attention toward the camera.

"It was totally not their plan to pose for the picture—it just ended up that way," Miley said.

The Buff Organization's "Happy Birthday Joyce" was devoted to Allison's friend Joyce Favrow, whose money bailed Frank Zappa out of jail in March 1965!

[...] The success of "Tijuana" enabled Buff to create more Hollywood Persuaders recordings, and back royalties from the record also helped bail Frank Zappa out of jail after he was arrested in March 1965!

This was not long after Dad's heart attack and since Frank had no money, Dad took out a loan for Frank's bail.

Frank tried to get the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] to defend him because he believe that this was a clear case of entrapment, but the ACLU said his case wasn't significant enough, so Dad had to hire a lawyer.

[...] After 10 days they got out of jail, and because they had nowhere else to go, Frank and Lorraine came to stay with Marcia and me at our apartment in Pomona.

[...] The San Bernardino Sheriff and district attorney's office wanted to charge Frank with the felony part of his indictment but when the judge heard the tape in chambers he laughed and told the prosecutor to reduce the charge to misdemeanor.

[...] Frank and Pete stayed with us for several days before they decided to go their separate ways.

Lorraine Belcher Chamberlain, Facebook, c. May 25, 2016

The court said [FZ] would be arrested if he was found in the company of a female under the age of 21. Motorhead and his mom had to chaperone us all the time, which became burdensome, to say the least. We had no money. I couldn't find a job. Frank was very depressed and angry about his treatment at the hands of the police, and had to move out of Studio Z. We were still very much in love, but I ran away to Seattle, not wanting to be a burden. Later, when he found me, he invited me to live [with his family]. Bobby [Zappa] saw me at the house once, but never knew what I was doing there. I was very friendly, happy to see him, but [Gail] was rude. He scurried out after talking to Frank, rather than hang around.

[...] My relationship with [FZ] only "ran its course" upon his death. We saw each other, loved each other all his life. I'm sensitive about the manner in which I was depicted. [FZ's] "biography" was dictated by Gail. Frank was excited about it, and I sent him the front page of the "Two a-go-go to jail" article, so he could put it in his book. Gail destroyed it, then insisted he not use my name, nor tell the truth about our relationship. He apologized to me profusely before it came out, saying Gail didn't want me to "become famous" from being part of his story. She took control of his own biography, and he was no longer excited about it.

April, 1965—The Soul Giants

There's a group playing somewhere. Roy Estrada, now a Mother, is part of it. He picks up Jim Black, another present Mother. Then Ray Collins joins the bunch. Ray always has been a troublemaker. He picks a fight with the guitar player. They come to blows. Ray wins. They need another guitar player. Somebody mentions Frank Zappa.

Zappa left his studio and went to live with Motorhead and his mother. While he was there he went into a bar and met a local group called the Soul Giants—Roy Estrada, Jimmy Carl Black, Davey Coronado and a couple of other guys. Shortly after he'd seen them, Zappa had a call saying the group had had a punch up and the guitarist had left, so he joined. "So I said 'let's stop playing other people's crappy kind of music and play our own,' and everyone approved except for Davey Coronado. He knew if you played original music in a bar in California you'd be out of a job and he was right. He knew everybody liked to hear the Stones, Ray Charles and 'High Heeled Sneakers'."

The

group that was to become the Mothers was working in the Broadside, a little

bar in Pomona, California.

Jim Black, the drummer, had just come to California from Kansas. He got together

with Roy Estrada, the bass player. They'de been working terrible jobs in Orange

County, which is a bad place to live unless you belong to the John Birch Society.

They got a band together with Ray Hunt on guitar, Dave Coronado on sax and Ray

Collins as lead vocalist. They called themselves the Soul Giants and they were

doing straight commercial rhythm and blues "Gloria," "Louie,

Louie," you got it. Then Ray Hunt decided he didn't like Ray Collins and

started playing the wrong changes behind him when he was singing. A fight ensued,

Ray Hunt decided to quit, the band needed a guitar player, so they called me

up. I started working with them at the Broadside, I thought they sounded pretty

good. I said, "Okay, you guys, I've got this plan. We're going to get rich.

You probably won't believe this now, but if you just bear with me we'll go out

and do it." Davie Coronado said, "No. I don't want to do it. We'd

never be able to get any work if we played that kind of music. I've got a job

in a bowling alley in La Puene, and I think I'm gonna split." So he did.

I think he's got a band now called Davie Coronado and his Sagebrush Ramblers

or something like that.

The Vi-Counts were an 11-piece band that was put together by an

early friend and myself, in which I played and managed. I was 17 years old at

the time. The band consisted of two trumpets, four saxophones, piano, guitar,

bass, drums and a singer. Later, I put together a 4-piece group named the Soul Giants. Our Vi-Count drummer did not want to do the club scene, so I was looking

for a drummer, and Jimmy had an ad at a local music store. He and his family

had just moved into the area, from New Mexico. We obtained a gig at a club called

The Broadside, where we met Ray Collins and added him to the group—as a singer,

of course.

Our guitar player was being drafted into the armed forces. Ray Collins

said he knew a guitar player that was looking for a group to play with. So,

Frank came during a week and sat in with us. At that time, it was like meeting

another guitar player, but with original music.

After reaching the point of playing mostly original music, Frank

asked for suggestions for giving the group a different name. I recall mentioning

the name 'The Mothers' (referring to motherfuckers). He said, "No! It will

not be accepted." We fiddled around with other names, but later, when he

went into Hollywood, he settled on The Mothers. When we signed with MGM, they

added 'Of Invention'.

I had a group (The Soul Giants)—I mean I was the one who took care of the management and booking and stuff. [...] We needed a drummer, so I put up an ad here at a local music store in Santa Ana (California) and Jim Black answered the ad and he joined. Then we got a gig through his wife . . . at a place called Broadside in Pomona—it was a brand-new place that was opening up. When we started performing there . . . evidently Ray Collins was working there as a carpenter. So before we started playing the (owner) asked us to take on Ray Collins as a singer and that's how we would get the gig. We said, "Of course we'll take him on." He started singing with us. (Later) we were going to lose our guitar player Roger . . . a local guy here from Orange County—he was going to get drafted.

[...] Dave Coronado—he would play two saxophones. He was . . . a Las Vegas-type of player. Then we had the drummer, which was Jim Black, and myself. Ray said, "I know of a guitar player." So, (on) a Wednesday evening, . . . Frank came over and sat in at the audition and we said, "Yeah, of course," and the rest was history.

[...] He had short hair. He was young and thin and ready to go. He had just gotten out of jail. That's what Ray said.

[...] So, we were playing Top 10 music at that time—"Gloria" and all that kind of shit. He said that he had music that he had written. He wanted to know if we were interested in learning it and looking through it, so we said, "Yeah." About that time, the sax player left, he quit—he wanted to go back to the Vegas circuit, so it was only the four of us then—Ray, Frank, Jim Black, and myself. We start rehearsing some of the music at the studio in Cucamonga. [...] The stuff that we learned was that stuff that's on Freak Out. I mean, that's the stuff that we first started learning. We rehearsed the music for months.

[Jimmy Carl] Black's brother-in-law got them an audition at a club called The Broadside in Inglewood. Roy Estrada remembers how, "It was a beer bar. The atmosphere inside was like the docks by the sea. You know, they had cork and a lot of fishing nets hanging on the side of the wall—it had some atmosphere to it. They had a fireplace in the middle. It was a nice club and it had a dancing area with a stage. So we got the job, and we opened the club."

The Soul Giants original line-up was I myself on drums, Roy Estrada on bass, Davy Coronado on sax, a guy called Larry on guitar and the singer was called Dave.

[...] Then we got this job as the house band at The Broadside club in Pomona. We played six nights a week, for about three months. We were making $90 each a week for the six nights, which wasn't that bad.

[...] The band was only going a few months when Larry the guitar player got drafted into the Army. We found a guy named Ray Hunt to replace him. Our singer Dave also got drafted so we needed to find a new front man.

A guy named Ray Collins had been coming to The Broadside all the time; he liked the band and what we were doing. [...] Skip, the owner of the club, said we could be the house band if we would hire Ray as a permanent member and front man. That was just fine with the rest of us since he sang much better than Dave.

The only problem was Ray Collins really didn't like Ray Hunt worth a shit. Before long, the two Rays got into an argument or rather a fistfight.

It was after Frank and I had recorded for a while that we actually got together, and then were apart for quite a few years, that I got hooked up with The Soul Giants at Pomona, which actually was about two blocks from where Frank and I met in the original bar. And then Frank became part of The Soul Giants.

I was living in Pomona again, Frank and I had parted after making records in Studio Z, and it was a period when I was just doing menial work as a carpenter and drinking away my paycheck every week, and I came upon some guys that were building a place called The Broadside—a great club, a great concept for a club—and he had other places and packed the people in. And I used to go there. And they hired a band called The Soul Giants, which had Roy Estrada (who became The Mothers' bass player), Jim Black, drums (The Mothers drummer), a horn player called Davy Coronado, a singer named Dave (I forgot his last name), and a guitar player named Ray Hunt. I guess his name is Ray Hunt—I had forgotten his name until I read it and what Frank said I said about him. But anyway, the club owner—I used to get up and sing. Also, another band that was there was the Three Days & A Night—Two Days—Three Days & A Night, which had Henry Vestine, guitar—

Charles Ulrich, July 3, 2013

Tom Brown's book Confessions Of A Zappa Fanatic contains a chapter on The Broadside, where Tom Brown performed (and was busted by the FBI) in 1968. Broadside Skip is mentioned in the chapter, so I asked Tom about him. Tom didn't remember Broadside Skip's last name, so he asked his friend and bandmate Gene Bridgham (also mentioned in the chapter). According to Gene, Broadside Skip was Skip Meyers.

In 1964, [Ray Collins] was supporting

himself by working as a carpenter, and on weekends he sang with a group called

the Soul Giants at a bar in Pomona called the Broadside.

Apparently he got into a fight with their guitar player, Ray Hunt, punched

him out, and the guitar player quit. They needed a substitute, so I filled in

for the weekend.

The Soul Giants were a pretty decent bar band. I especially liked Jimmy Carl

Black, the drummer, a Cherokee Indian from Texas with an almost unnatural interest

in beer. His style reminded me of the guy with the great backbeat on the old

Jimmy Reed records. Roy Estrada, who was Mexican-American and had also been

part of the Los Angeles R&B scene since the fifties, was the bass player.

Davy Coronado was the leader and saxophone player of the band.

I played the gig for a while, and one night I suggested that we start doing

original material so we could get a record contract. Davy didn't like the idea.

He was worried that if we played original material we would get fired from all

the nice bars we were working in.

The only things club owners wanted bands to play then were "Wooly Bully,"

"Louie Louie" and "In the Midnight Hour," because if the

band played anything original, nobody would dance to it, and when they don't

dance, they don't drink.

The other guys in the band liked my idea about a record contract and wanted

to try the original stuff. Davy departed. It turned out that Davy was absolutely

right—we couldn't keep a job anyplace.

[Ray Hunt] used to play the wrong thing behind me—the wrong chord-changes or something—so finally I mentioned it to Roy and Jim, 'cause Roy and I had gotten pretty close by then—what was going on. And Roy said, "Yeah, I noticed it too." So it all came down to the fact that Ray Hunt didn't want to be part of the band, so we just got together after the show one night, and said, "OK, Ray, you're not doing it right—so don't do it." So he said, "Great, so I'm leaving." So I said, "Don't worry about it, 'cause I know a guy that I worked with before from Ontario/Cucamonga named Frank Zappa, and I think maybe he'd like to be in the band." So I called Frank and he became part of the band. But that's very strange that out of all Frank's memory-banks, he should pull out something like that, which isn't true at all, actually.

Ray said he knew a guy who played and that his name was Frank Zappa. Ray said, "I'll have him come in. He just got out of jail." Supposedly he had been there for making party tapes with this girlfriend of his.

We needed a change from Wichita. My wife's father lived in Santa Ana, near Los Angeles. California, man! Hollywood! Two weeks after we arrived, I met Roy in a music store where my name was up on the board as an available drummer. We started the Soul Giants to play R&B covers with Davy Coronado on sax and two others. We were doing OK—$90 a week, not bad for 1964. Then the singer got drafted, and we found Ray Collins. Next, the guitarist got drafted, and Ray mentioned a guy called Frank Zappa who'd just got out of jail. We auditioned Frank, who was kind of freaky-looking, but I liked him a lot. Within a month, Davy Coronado left, and Frank said, "If you guys'll learn my music, I'll make you rich and famous." He took care of half that promise. I got famous, but I damn sure didn't get rich!

C: How did you meet up with Jimmy Carl Black?

Z: He was working at a bar.

[FZ] originally joined a rock'n'roll band after getting out of jail. The band was already together but it didn't take Frank long to swing things his way and take over completely—redubbing the group the Mothers of Invention (or the Muthers—until MGM records changed it).

Roy Estrada, to Giuliano "apostrophe," Rome, January 23, 2005

We were playing at the Broadside, the band was called The Soul Giants . . . The guitar player had to go in the Army and Ray Collins knew this guy FZ . . . Yes he had just come out of jail .

In 1964 I moved to California, and two weeks after arriving I met up with Roy Estrada. Together we formed a band called The Soul Giants, played around for maybe a couple of months and then Ray Collins joined the band as lead singer. Right after that our guitar player, Ray Hunt, got drafted, so we were left looking for another guitarist. Ray Collins said he knew a guy that he'd done some work with before, Frank Zappa, who had been spending a little time in jail in San Bernardino County for selling pornographic tapes to the vice squad. Anyway, Frank came down and tried out with the band and liked what we did, and we liked what he did, so he joined. A month later the saxophone player, Davey Coronado, left the band which left the position of leadership wide open. Frank took over as leader, and his very words were "If you will play my music, I will make you rich and famous."

We needed a guitar player and we auditioned Zappa. He had to audition for the Soul Giants. And he passed the audition and he joined the band, and about a month after he joined the sax player, Davy Coronado, who was the leader of the band at that time, he went back to Texas and . . . he quit the band and went back to Texas and then Zappa took over. That's when he said "If you'll . . . I'll make you rich and famous . . . If you'll play my music, I'll make you rich and famous." His exact words.

The guitar player was this really weirdo guy named Ray Hunt. He wasn't even a good guitar player, but a terrible guitar player.

Well, that's what Davy [Coronado] was screaming at him about, man. "Play some rhythm and blues. You're playing some weird shit and we don' know what it is" (laughs). And Ray Collins knew this guy that had a studio, named Frank Zappa, and he called him up and asked him if he wanted to audition for the band. He came down the next day and auditioned . . . Motorhead came with him, so Motorhead was there from the beginning as well.

Davy [Coronado] didn't want to play Frank's music, really. But that's not the real reason. It's because he was tired of California, man. He wanted to go back to . . . he wanted to go back to Texas. And he did. He used to have a tex-mex band in . . . quite famous one in Texas. I mean, in the area it was, you know. Where he was, he was from around Brownsville . . . Laredo, Texas. That was where he was from.

Circa 1964, Collins joined the Soul Giants, an R&B cover band, by accident. When the band auditioned at the Broadside, the club owner insisted that Collins, his friend, would have to replace the singer if the band wanted the gig.

"I felt kind of awkward about it, someone firing someone else and giving me the job," Collins says.

The band consisted of drummer Jimmy Carl Black, bassist Roy Estrada, saxophonist Davy Coronado and guitarist Ray Hunt. Hunt, however, was incompetent or purposely messed up to be spiteful, Collins relates.

"I was new to the band but it was up to me to get rid of him," Collins says. After the deed was done—no punches were thrown, he insists—he made a fateful suggestion.

"I told them, 'I know a guitarist in Cucamonga. His name's Frank Zappa,'" Collins says.

They'd been in existence for maybe three months prior to the time that I came in as substitute guitar player. We played R&B/bar-band music.

So we asked Ray if he knew any other guitar players and he said, "Yeah, I know this guy who's just got out of jail." We said, "What was he in jail for?" and he told us, "Oh, he made some pornographic audio tapes and sold them to the vice squad but it was all a set-up." We had nothing to lose so we said, "Let's get him down for an audition, what's his name?" Ray said, "Frank Zappa."

Ray told us that Frank was running a little recording studio called Studio Z out in Cucamonga. They had recorded some stuff there together and some of it had even been released on a few small labels. Frank arrived at the audition in a car driven by a guy called Motorhead. We liked the way Frank played. He was a strong rhythm player although he wasn't a very good lead player back in those days. Little did we know what was going to happen!

Frank joined the band in April. We were playing a lot of gigs at The Broadside and Frank was very grateful to have a job that was paying $90 a week. We went over to his house a couple of times in G Street, Ontario. He was just getting ready to move out; he was getting divorced. When I met his wife Kay I thought, "God, Man! Why are you moving out of the house? She's a Babe!" I thought she was a good-looking lady but there were about nine cats in the house too! Roy's father always said to us, "Don't trust anyone that has that many cats!"

Jimmy Carl Black was hocking some cymbals so he could eat, and he ran into

Roy (Estrada) at the same hock shop. They started talking and formed a group

called the Soul Giants. Ray (Collins) joined them and they were appearing at

a club called the Broadside in Pomona. Ray had a disagreement with the guitar

player with the group and when they soon found themselves without a guitar player,

they called me, asked me to substitute. I thought it was a spiffy little group

and I proposed a business deal whereby we'd form a group and make some money,

maybe even a little music . . . but initially it was a financial arrangement.

When you're scuffling in bars for zero to seven dollars per night per man,

you think about money first.

The Soul Giants were mainly an R&B band but we played a few current hits because we were playing in bars mostly. We did do a few songs by Frank. You know we had Ray Collins as the lead singer and he is one of the best R&B singers around, in my opinion.

They were pretty good. I already knew that Ray [Collins] was a good singer;

we'd recorded before that. But the thing that impressed me about the Soul

Giants, being a rhythm & blues buff, was Jimmy Carl Black—the only

drummer I'd ever seen who actually could sound like Jimmy Reed's drummer.

Think about it: the absolute disregard for technique, know what I

mean? The total dedication to going boom-bap, boom-bap. A rare talent.

I told 'em, "Let's learn more original songs and try and get a record

contract." And the sax player, a guy named Davy Coronado—it was his

group—he says, "You can't do that. The minute you start playing original

music you'll get fired from these clubs." And he was right. We learned

original music and we got fired . . . and fired and fired and fired.

Anyway, Frank came down and tried out with the band and he liked what we did, and we liked what he did, so he joined. A month later the saxophone player Davey Coronado left the band, leaving the position of leadership wide open. Frank took over as leader, and his very words were, "If you will play my music, I will make you rich and famous."

Captain Glasspack & His Magic Mufflers

When Frank suggested that we start to play some original material and try to get a record contract, Davy Coronado said, "No, that's the end of it for me. We'll never play in The Broadside again if we play original music." Davy was very attached to The Broadside, he liked it there, but he quit the band and moved back to Texas. So The Broadside club stopped when Davy left the band because he was thick with the management. They said, "You can keep the job but you have to get a sax player and it better be one like Davy Coronado!"

We used to work in Torrance at a really wretched place called The Tom Cat, and then after The Tom Cat we go to jam-sessions at a place called Lambs, and at that time the band was known as Captain Glasspack & His Magic Mufflers, and they kept throwing us out of those jam-sessions because there's this old pig that play the piano there, it was sort of a mistress of ceremonies, and she was embarassed to introduce us when we wanted to get up and rock out, "You guys gotta be kiddin' with a name like that!"

Having begun to try out Zappa's compositions, the Soul Giants no longer seemed like an appropriate name for the band [...]. They started toying with other names, and for a brief period apparently reverted back to an old name The Blackouts [...]. For a while they even called themselves Captain Glasspack & The Magic Mufflers. "I think he [Zappa] was asking us for ideas for our name after a while," says Roy Estrada. "If memory serves, I suggested 'Muthas', and he said, 'Ahhh, I don't like that name.' (laughs) So we forgot all about it. Later on he said the Mothers was all right."

Giuliano "apostrophe," January 24, 2005

Capt. Glasspack and His Magic Mufflers . . . Roy [Estrada] said that it's one of the names that came up but he didn't think they ever played with that name . . .

We called ourselves The Blackouts at first, and then we changed our name to Captain Glasspack and his Magic Mufflers for one gig and finally settled on the name The Mothers. MGM Records, when we signed the record deal, were the people who changed our name to The Mothers of Invention.

One of the places we got fired from was the Tomcat-a-Go-Go in Torrance. [...]

A converted shoe store in Norwalk with a beer license also fired us. Of course

the gig didn't pay that well: fifteen dollars per night divided by four guys.

There's always the hope held out that if you stick

together long enough you'll make money and you'll get a record contract. It

all sounded like science fiction then, because this was during the so-called

British invasion and if you didn't sound like the Beatles or the Stones, you

didn't get hired. We weren't going about it that way. We'd play something weird

and we'd get fired. I'd say hang on and we'd move to another go-go bar—the

Red Flame in Pomona, the Shack in Fontana, the Tom Cat in Torrance.

Sometime before this I'd had a group called the Mothers, but while all this

was going on we were called Captain Glasspack and His Magic Mufflers. It was

a strange time. We even got thrown out of after-hours jam sessions. Eventually

we went back to the Broadside in Pomona and we called ourselves the Mothers.

It just happened, by sheer accident, to be Mother's Day, although we weren't

aware of it at the time. When you are nearly starving to death, you don't keep

track of holidays.

We changed the name of the band a few times. Right after being called the Soul Giants we were called The Batmen for a while. We played one gig as Captain Glasspack and his Magic Mufflers. We were auditioning all over the place just trying to work. In May, we changed our name to The Mothers. Actually, it was spelt Muthers in the beginning!

[...] We managed to get a gig at the Tom Cat à Go-Go in Torrance for a month. It was a real go-go joint. We had to play "Woolly Bully" and "Louie Louie" about ten times a night. We had to play what the girls wanted us to play. It was their show so they chose the numbers. We did five 45-minute sets a night, six nights a week. We were making $90 a week and believe me we fucking earned it.

All the time, we would try to put a few of the original songs in. We could play "Anyway The Wind Blows" and "I'm Not Satisfied," the girls liked those songs. Every once in a while, we would do "Memories Of El Monte" and the reason that we got away with doing that was because everybody thought it was such a joke.

[...] We played around a few other go-go joints. I remember The Red Flame in Pomona, The Shack in Fontana and the Brave New World, which wasn't a go-go club and was the first gig we did in Hollywood. Frank had met some people in the Hollywood scene and had gotten us the gig. We played a few other little gigs and occasional one-nighters.

Alice Stuart

Then we decided we were going to the big city—Los Angeles—which

was about thirty miles away. We had added a girl to the group, Alice Stuart.

She played guitar very well and sang well. I had an idea for combining certain

modal influences into our basically country blues sound. We were playing a lot

of Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf-type stuff. Alice played good finger-style guitar,

but she-couldn't play "Louie, Louie," so I fired her.

Frank was starting a group. He had nothing to his name but a very good guitar and a very beat-up old car—yet he knew exactly what he wanted to do. We got a group together that consisted of Jimmy Carl Black, Ray Collins, Roy Estrada, Frank and myself, playing great beaters like "Midnight Hour." I went beserk after about three months with Frank doing his Chicano rap, so I split . . .

Alice Stuart, interviewed by Mike Plumbley, Clearspot, August, 1998

Actually, Frank and I met in Los Angeles in a coffeehouse. Seems we were both waiting to meet the same person, a great guitarist named Steve Mann. We were about the only people there and we got to talking and when we finally gave up waiting for Steve, ended up leaving together. We had a fast and furious love affair and tried to incorporate music into the equation. His music was so much different than mine that it was destined to end in disappointment. We loved and cared about each other though. That was when I was trying to go from a folkie to a rocker.

When I met Frank, I was just becoming interested in playing the electric guitar. I really didn't have a clue about how to do it. I'm figuring this was 1965, and I had been playing acoustic guitar for 5 years or so, a lot of Delta Blues and Dylan songs (what a combination) and was firmly rooted in the folk club and festival scene. I was very excited about the possibility of playing in a ROCK band.....wow. So, because of my insistent whining, Frank got me this silly little red fender with terrible action that was almost impossible to play. I think he just wanted to squelch my ideas of playing electric; he really wanted me to play acoustically. Believe it or not, we did 'Hey, You Get Off of My Cloud'—that and some Muddy Waters' stuff. I only played a couple cheesy venues in East L.A. and somewhere else I can't recall.

As far as the way I was treated goes, I don't know that anyone in the band actually took me seriously. I mean, Frank had this wild hair idea about how this would just be so cool—this fusing of my delta guitar playing and his electric thing. The band was pretty much a blues band at the time. He hadn't figured out exactly what he wanted to do; he was experimenting too. Women in the music business are always judged more harshly than men. And it was worse back then. I do think it was especially true at that time that a woman had to be a little better than her male counterpart to get much credit. But, I always figured I would earn respect and didn't want it unless I could deliver.

I'd like to tell you the strange story of how Frank and I met. We had come into this coffee house in Hollywood, separately, called the 5th Estate, I think. We were both in there for a couple of hours and we were the only people in there. Finally, he introduced himself and asked me why I was hanging around so long. I told him I was there to meet a friend, Steve Mann (a fabulous guitar player). Well, it turns out that's why HE was there, too. We got to talking and waited another hour or so, and finally gave up on Steve. We spent the next few months together, both musically and personally. If I hadn't been such a mess at the time emotionally, I might have never left.

We met at a coffeehouse in Santa Monica in 1964. We had

come in separately and had both been there for about 2 hours. We got to talking

and found out we were both waiting to meet the same person, Steve Mann, a great

guitar player who had been a major influence on many guitar players. We left

together after about 3 hours (and a LOT of coffee).

We immediately fell into a warm and comfortable relationship and

were inseparable for a few months. I was drawn to his energy and sense of ambition.

He knew what he wanted and was a good communicator.

He had a blues band when I met him, just 4 people and the Turtles

sang with him occasionally. I was looking to move from acoustic guitar to electric,

but he wanted to incorporate my acoustic delta style with his electric leads.

It was just a blues band, but Frank had been working on some new

songs with these strange, complicated chords that went right over my head.

We were playing "Get Off of my Cloud" and straight blues

tunes. But his new songs that he was working on (that ended up on Freak Out)

stood apart from anything I'd ever heard before. (By the way, he spelled my

name wrong on Freak Out, the bum).

I left right before the first recording session.

[I didn't tour with his band], it was a very short time, a matter of months.

[I was playing a] Martin D-18 that I still have. Frank bought me a little red Fender

electric and it was a real dog, like a 3/4 size or something. Really hard to

play. I didn't have my own electric guitar yet.

There was a girl guitar player called Alice Stuart on the scene. I think she and Frank had a little thing going. She was a good player, but very much a folkie-type player. However, she became quite a blues player. I think Alice only played at the Brave New World and a couple of those little one-off gigs. It was a nice idea and she was a nice woman, but I didn't think that she fitted in that well and ultimately, I don't think Frank did either.

Tom Wilson

David Anderle was a young talent scout for MGM/Verve in Los Angeles in 1965. [...] Anderle saw the Mothers at the Red Velvet club and was smitten. He was having a hard time getting anyone at the label to take Zappa seriously when Wilson was hired as head of East Coast A&R. Anderle coaxed Wilson out from New York to see the band, and to Anderle's amazement, Wilson "got them" right away and the band was signed, launching the careers of both Zappa and Anderle.

In 1964, [David Anderle] became West Coast talent director at MGM, which owned Verve Records at the time. After seeing Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention in 1965, Anderle pushed to get the act signed to the label, but met considerable resistance within Verve. Anderle convinced Tom Wilson to sign the Mothers and produce their album.

Reportedly taken by Zappa's Watts riot song, "Trouble Every Day," [Tom] Wilson investigated further, liked demos of "Any Way the Wind Blows" and "Who Are the Brain Police," and got Verve Records (MGM subsidiary) to put the Mothers of Invention (MGM made them add "of Invention") under what Zappa calls "contractual bondage."

The Mothers of Invention, riding the crest of Los Angeles freakdom, were signed to MGM-Verve in November of 1965

Our manager Herb Cohen dragged him away from a girl that he had sitting on his lap at a Hollywood club down the street from where we were working at the Whisky-A-Go-Go. We have to be appreciative of Tom. He's passed away now but he was visionary. He signed the Velvet Underground and a number of other really obscure groups at that time. And we were just another of his obscure groups that he was producing.

FZ, interviewed by Barry Miles, September 13, 1970

Herbie knew Tom Wilson, and sort of dragged him away from fun and merriment at this— He was at this club down the street from the Whisky A-Go-Go, he was at the Trip. And we were working a replacement job or something at the Whisky A-Go-Go. And Herbie got Wilson to come down and listen to us.

Prior to that, we had made some demos at Original Sound, had sent them to MGM and a bunch of other companies. And we had been turned down by everybody in the business. And so MGM was sort of like a last resort. And we hadn't received any word as to the acceptance of our demos from MGM. So Herbie knew that Wilson was the guy to talk to, saw Wilson in this club, and made him come down and listen to us at the Whisky A-Go-Go.

Chris August: How were you able to get a recording contract, how were you able to get on Verve?

Frank Zappa: That was an accident. We had gone around to all the record companies, shopped our demos around and done all the things that a new group does in Hollywood to get somebody at a record company to listen to them, and been turned down by everybody. And finally this guy, Tom Wilson, who was the producer at MGM, was down the street at one club while we were working at the Whiskey a Go-go, and he was induced to be dragged away from his lady friend and come down and see us play just for a moment. And he walked in while we were playing the Watts Riot Song.

Synapse: "Trouble Coming Every Day."

Zappa: Right. That was a rhythm and blues kind of number. He walks in and he sees the band, sees us play that. We finish the set, I come out and shake hands with him, he said he liked it. He said that he thought we could make a deal, and he walked away thinking that he had signed a white rhythm and blues band. And they gave us the astounding sum of $2500.00 to sign the contract, and we went in and started making the record the first song we recorded was "Any Way the Wind Blows," and the second song we recorded was "Who are the Brain Police;" and that's when the phone calls started going out to New York, You know, uh, oh, what happened?

Synapse: Were they committed to manufacturing the first one?

Zappa: That's right, yeah it was already signed, the money was spent and they didn't really know what they had bought. So, like I said, It was an accident. If he hadn't been there and we hadn't been there and we hadn't been playing that one particular song when he came in; if it hadn't been a certain hour of the night where the crowd at the Whiskey a Go-go was up dancing and looking like they were having a good time to this particular number, well, it might not have happened.

Not long after [Halloween at the Action], Johnny Rivers went on tour and we were hired as a temporary replacement at the Whisky-a-Go-Go. By chance, Tom Wilson, a staff producer for MGM Records, was in town. He was up the street, at the Trip, watching a 'big group.' Herb Cohen talked him into a quick visit to the Whisky. He walked in while we were playing our 'BIG BOOGIE NUMBER'—the only one we knew, totally unrepresentative of the rest of our material.

He liked it and aoffered us a record deal (thinking he had acquired the ugliest-looking white blues band in Southern California), and an advance of twenty-five hundred dollars.

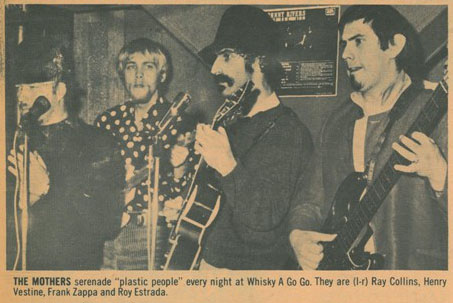

Tom Wilson, who was producing records for MGM at the time, came to the Whiskey A-Go-Go while we were a five-piece group, while Henry Vestine was still with us.

Wilson found Zappa, seeing The Mothers for the first time at the Whiskey at the end of November '65. He only watched and listened to them for a few minutes on that first occasion. [...]

There may have been a few record company execs hanging around who didn't know what they were in for at that point, but Tom Wilson certainly did. He saw them a number of times before he signed them, and the go-ahead for Frank to prepare material for an album didn't come until 1 March 1966. At least, that's the chronology as Pam Zarubica recalls it.

While in L.A. in late November 1965, Wilson was escorted by Mark Cheka and Herb Cohen to catch the last few minutes of a set by The Mothers.

In January 1966 [Tom] Wilson visited the [West] Coast. One evening at the Trip he met Herb Cohen and accompanied him to the Whiskey to catch the Mothers.

[Sterling] Morrison: "[...] We made the album ourselves and then took it around because we knew that no one was going to sign us off the streets. And we didn't want any A&R department telling us what songs we should record. We took it to Ahmet Ertegun and he said, 'No drug songs.' We took it to Elektra, and they said, 'No violas.' Finally we took it to Tom Wilson, who was at Columbia, and he said to wait until he moved to MGM and we could do whatever we wanted with on their Verve label, which turned out to be true and MGM did sign us. They signed The Mothers of Invention at the same time, trying to revamp Verve and go psychedelic, or something." [...]

Warhol: "[Tom Wilson] was a friend of Nico's. When they went with MGM, Tom Wilson was the person there."